A State Beheaded: The Political Fall of Land’s Advocate Johan van Oldenbarnevelt

In the early morning of 13 May 1619 the Binnenhof in The Hague, the political centre of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands, filled with thousands of curious people from inside and outside the city, all waiting with baited breath for the moment one of the most powerful men of the time would be sentenced for high treason. A few hours later the 71-year-old Land’s Advocate Johan van Oldenbarnevelt mounted the wooden scaffold erected specially for the occasion at the entrance of the Grote Zaal or Great Hall (now the Ridderzaal). Having spoken his famous last words, “Make it short, make it short”, to his servant who had come to bid him farewell, Oldenbarnevelt knelt in prayer, and was subsequently beheaded. How did it come to this?

Portrait of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt, ca. 1616

Portrait of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt, ca. 1616© Rijksmuseum

Having graduated from the Latin school in his birthplace of Amersfoort, in the summer of 1566 Van Oldenbarnevelt set off for Leuven to study law. His time at one of Europe’s greatest universities brought him into direct contact with the unrest of the Great Iconoclasm, which was raging through the Habsburg Netherlands. This large-scale destruction of images of saints was the prelude to the revolt that broke out two years later against the sovereign ruler Philip II of Spain. On his return from his research trip abroad in 1570, Van Oldenbarnevelt remained neutral in this conflict against the Habsburg authority, but this changed two years later when the regions of Holland and Zeeland came to form the centre of the resistance. The young jurist moved to Delft to join the leader of the Dutch Revolt, William of Orange.

Pompeo Leoni, King Philip II of Spain, c. 1580

Pompeo Leoni, King Philip II of Spain, c. 1580In 1581 the seven northern regions of the Habsburg Netherlands decided to depose Philip II from his position as territorial lord. They immediately went in search of allies to take over sovereignty. By this time Van Oldenbarnevelt had climbed to the highest municipal office (city pensionary) of Rotterdam. As representative of Holland’s seventh city he had access to the States, the most important executive board of the region, and he sat on various committees. Thus in 1585 Van Oldenbarnevelt accompanied a diplomatic mission to England to offer sovereignty to Elizabeth I. The English queen refused, but she did send troops, money and her confidant Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, to help the rebels.

Beheading of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, Jan Luyken, 1698

Beheading of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, Jan Luyken, 1698© Rijksmuseum

On his arrival in the Netherlands, Leicester was soon keen to expand his powers. The States of Holland refused and in 1585 appointed Maurice, son of William of Orange who had been killed in 1584, as stadholder to restrain the English governor. A year later Van Oldenbarnevelt was also appointed as Land’s Advocate. His resoluteness and legal knowledge suited him to representing the interests of the region. With the assent of his masters, the States of Holland, Van Oldenbarnevelt soon succeeded in expanding his office as the legal advisor of Holland to the most important spokesman of the most important region. He also saw off the English governor and in 1587-1588 provided the States of the seven regions with a theoretical underpinning for drawing up power. With Maurice as military strategist at his side, the Land’s Advocate

was then at the head of a state in the making: the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands.

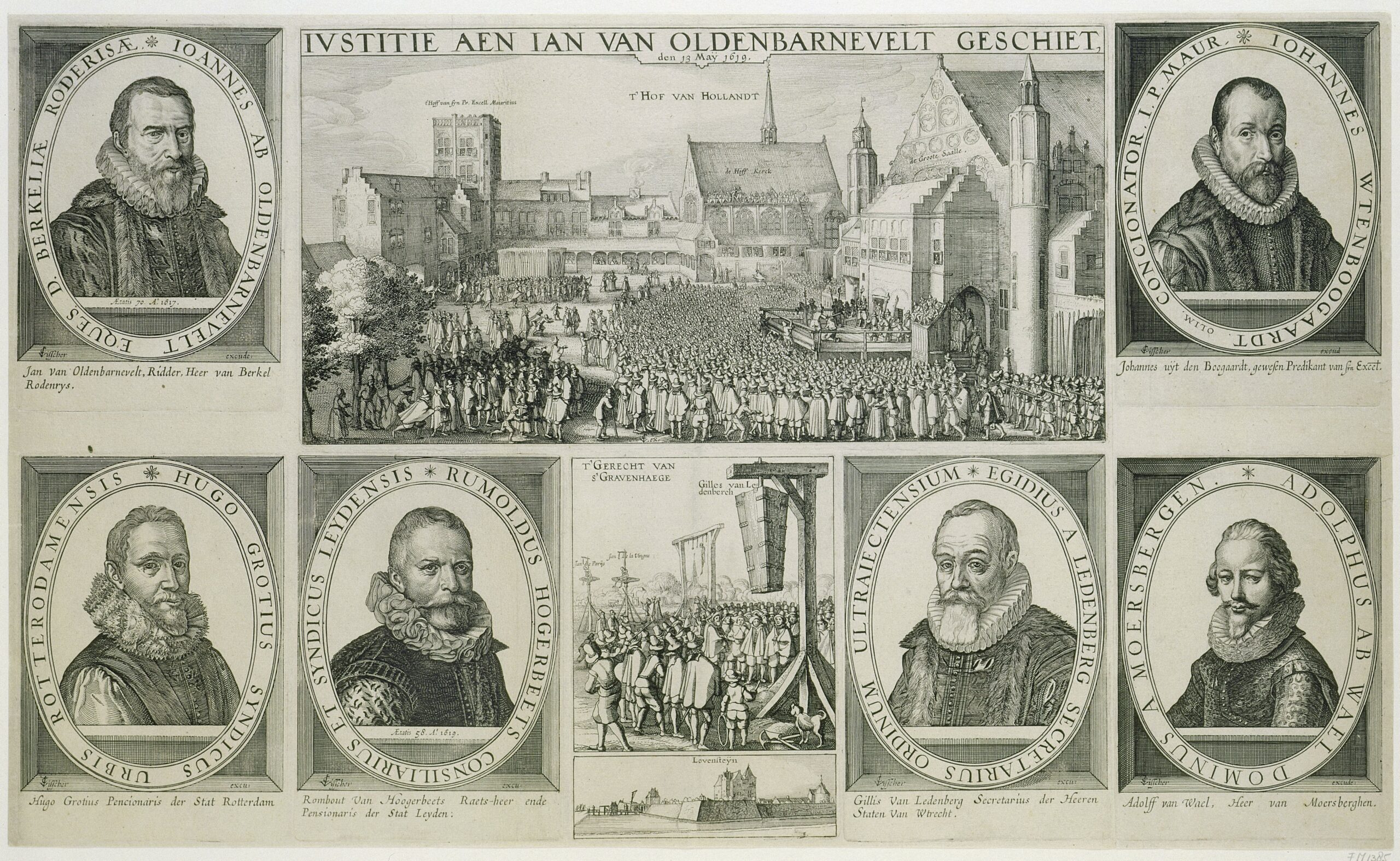

Beheading of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, 1619, Claes Jansz. Visscher (II), 1619

Beheading of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, 1619, Claes Jansz. Visscher (II), 1619© Rijksmuseum

For a long time the two men collaborated well. Van Oldenbarnevelt ensured the necessary cash flow, so that Maurice could focus entirely on his role as general and conducting the war. Having achieved several military successes, the stadholder felt a growing need to talk about war policy, but this brought him into conflict with Van Oldenbarnevelt, to whom he had left the political side of his office. The first clash took place in 1600, when Maurice was compelled to conquer the privateers’ breeding ground of Dunkirk, deep in the enemy’s territory. Thanks to the well-practised army, Maurice narrowly achieved a victory, but he personally resented Van Oldenbarnevelt for insisting on this military campaign. In 1607-1609 tensions increased due to different views on agreeing a truce with Philip II. As commander-in-chief Maurice wanted to continue the war in order to definitively defeat Spain, but Van Oldenbarnevelt saw no point in this and insisted on a ceasefire. In the end the political and religious contrasts during the Twelve Years’ Truce (1609-1621) placed Van Oldenbarnevelt and Maurice in direct opposition.

Executioner’s sword used to behead Oldenbarnevelt, anonymous, 1600 - 1625

Executioner’s sword used to behead Oldenbarnevelt, anonymous, 1600 - 1625© Rijksmuseum

With the support of the States General, in August 1618 Maurice had his opponent arrested. Van Oldenbarnevelt had been imprisoned for almost nine months when a special court found him guilty of high treason. The Land’s Advocate’s policy was deemed to have endangered the internal security of the Republic. The sentence ‘met den Swaerde’ (by the sword) was carried out on 13 May 1619. Four hundred years later Van Oldenbarnevelt’s case remains a matter of public concern: did the Land’s Advocate receive a fair trial or had the death sentence already been decided? This question has never received an unequivocal answer.