Edward Winslow: The Forgotten Pilgrim Father

In 1620, a group of religious refugees from Leiden travelled across the Atlantic to settle in North America. On board the Mayflower was also Edward Winslow, separatist, governor and international diplomat. Although he was one of the Pilgrims’ most important leaders, Winslow is perhaps the least known today. Without him, however, the history of the United States would have looked different.

In 1625, Jan de Laet included a chapter about the Pilgrims’ new colony in New England, Plymouth in his comprehensive book about current exploration and European expansion. De Laet was a leading political and lay religious leader in Leiden. Through his acquaintance with those Pilgrims who had remained, De Laet had direct access to news from the colony.

This included the 1622 booklet known as Mourt’s Relation that the Pilgrims had had printed in London to attract support and urge new participants to join them in America. De Laet also mentions having read private correspondence sent by the colonists back to family and friends. His interest in the new settlement was understandable, as New Netherland was a similar experiment begun just a year earlier at the Hudson River, the Pilgrims’ intended destination. And as one of the directors of the newly founded West India Company, De Laet was directly involved in the running of New Netherland.

Adam Willaerts, The Departure of the Pilgrim Fathers from Delfshaven in the Netherlands on their Way to America, 1620

Adam Willaerts, The Departure of the Pilgrim Fathers from Delfshaven in the Netherlands on their Way to America, 1620© Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Pilgrims were Separatists who had withdrawn from the Church of England. To escape increasing persecution they fled into exile in Leiden in The Netherlands. In 1620, around a hundred of them sailed via the English harbor of Plymouth to New England to found a colony of their own. Before landing, they signed a mutual agreement (the “Mayflower Compact”) to elect their own governor and to accept democratically approved laws and regulations. They asserted that no superior authority had the power to accept, limit, or reject their decisions (unlike the Virginia House of Burgesses, active since 1619, but subordinate to approval or rejection from the Virginia Company in London).

Since the nineteenth century, the Mayflower Compact has been extolled as an important document in the development of democracy in America. Historians generally have found no influence from the document outside the colony itself; some even dismiss it as a temporary, ad hoc attempt to calm a dispute that was soon forgotten. That interpretation is however contradicted by the fact that the Mayflower Compact was cited as the foundation of colony government repeatedly throughout the colony’s history, for example in revisions of laws.

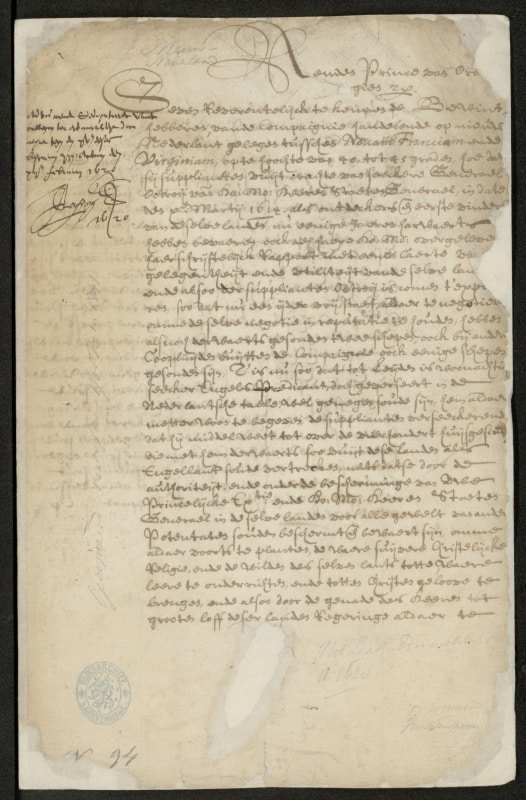

Request of the New Netherland Company to Prince Maurice of Orange to be allowed to settle a number of Pilgrims from Leiden on the Hudson River, 12 February 1620

Request of the New Netherland Company to Prince Maurice of Orange to be allowed to settle a number of Pilgrims from Leiden on the Hudson River, 12 February 1620© National Archives of the Netherlands

Marriage Dutch Style

One of the early decisions taken by the colonists is that marriages would be solemnized by magistrates and would not be church events, unlike the requirement in England that all marriages be solemnized by a priest of the Church of England. William Bradford remarked on this in his memoir, Of Plymouth Plantation:

“May 12 [1621] was the first marriage in this place, which according to the laudable custome of the Low-Cuntries, in which they had lived, was thought most requisite to be performed by the magistrate, as being a civil thing, upon which many questions about inheritances do depend, with other things most proper to their cognizance, and most consonant to the scriptures, Ruth 4, and no where found in the gospel to be laid on the ministers as part of their office. ‘This decree or law about marriage was published by the States of the Low-Countries Anno: 1590. That those of any religion, after lawful and open publication, coming before the magistrats, in the Town or Stat-house, were to be orderly (by them) married one to another.’ Petets Hist. fol. 1029. And this practice hath continued amongst, not only them, but hath been followed by all the famous churches of Christ in these parts to this time, – Anno 1646.”

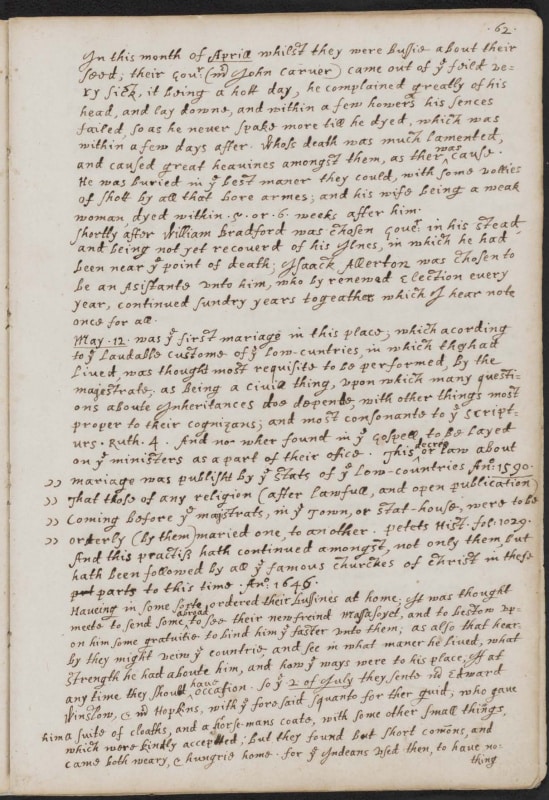

Page 62 from the manuscript of Bradford’s Of Plimoth Plantation, with the reference to marriage legislation. State Library of Massachusetts

Page 62 from the manuscript of Bradford’s Of Plimoth Plantation, with the reference to marriage legislation. State Library of Massachusetts© State Library of Massachusetts

So Dutch law was explicitly the source for the Pilgrims’ introduction into English legal practice in New England, of civil marriage and consequently separation of church and state. Regardless of the Mayflower Compact’s subsequent significance (or lack thereof), the Pilgrims’ innovation regarding marriage was important beyond their colony’s borders, continuing long past the time of the colony’s institutional existence (which ended in 1691-92). But a couple of questions arise. First, what was Bradford’s source? Because he gives the folio number, we know that he was referring to Edward Grimeston’s A Generall Historie of the Netherlands (1608), which was largely a translation of a work by Jean François le Petit, with additional material from Emanuel van Meteren, François Hottoman, and Sir Roger Williams. Bradford repeats that nearly verbatim.

Second, who got married in 1621? The answer is: Edward Winslow. Trained as a printer, he came to Leiden ca. 1617, where he assisted William Brewster in putting out books supporting Separatism and criticizing the Church of England and its head, King James I. His first marriage, on May 12, 1618, had been registered at Leiden’s city hall. Unfortunately, his first wife (Elizabeth Barker) had died on American soil in the first winter, which took a heavy toll on the Pilgrims. When the spring of 1621 arrived at Plymouth, Winslow married Susannah, widow of William White, coincidentally also on May 12.

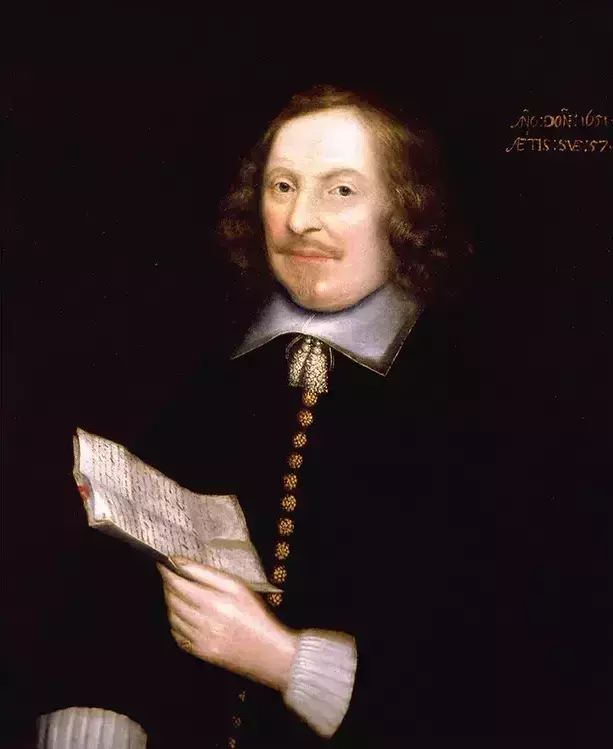

Portrait of Plymouth Colony Governor Edward Winslow by the School of Robert Walker, 1651, Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, Massachusetts

Portrait of Plymouth Colony Governor Edward Winslow by the School of Robert Walker, 1651, Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, Massachusetts© Wikimedia Commons

Winslow’s rise

In Plymouth, Winslow rapidly took important roles in the colony’s contacts with the Pokanoket Indians. The colony also sent him to London several times in the 1620s as their agent in negotiating repayment of funds borrowed from the “adventurers” as the investors were called who had funded the project but remained in England. Winslow joined forces with the colony’s other agent, Isaac Allerton, to obtain additional loans. He arranged for the first cattle and horses to be brought to the colony. Winslow was elected governor of the colony in 1633. This was a one-year position. During his tenure, Winslow was responsible for revising the laws and instituting clarity in archival record-keeping for the government’s decisions.

The next year, Winslow, no longer governor, returned to London. His mission was to defend the colony’s actions in several conflicts with the Dutch about Plymouth’s land claims at the Connecticut River and with the French at the Kennebec River concerning land belonging to Plymouth (in modern Maine). He also opposed emerging plans of Archbishop William Laud and Sir Ferdinando Gorges to suppress puritanism in New England and install an established Church of England, together with new government officials firmly loyal to the king.

He arranged for the first cattle and horses to be brought to the colony

Winslow was arrested on Laud’s orders, and imprisoned for seventeen weeks, until his friends and well-placed relatives managed to obtain his release. He had been charged with unauthorized preaching, which he admitted to having done occasionally, and with presiding over civil marriages as magistrate.

Winslow’s defense was that “marriage was a civille thinge, & he found no wher in ye word of God yt it was tyed to ministrie… bsids, it was no new-thing, for he had been so married him selfe in Holland, by ye magistrats in their Statt-house.”

Winslow returned to New England, where he was once again chosen as Plymouth’s governor on January 5, 1635-36. He presided over the completion of the revision of the colony’s laws, thus finishing the work he had begun in 1633. Bradford resumed the governorship in 1637, while Winslow was once again magistrate. Participating in routine official actions, Winslow again became involved in defending the colony, this time against Samuel Gorton, who challenged the legitimacy of the New England churches and the colonies’ governments. This increasing threat, together with fear of Narragansett Indian attack against the colonists, inspired the combination in 1643 that is known as the United Colonies of New England. The colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, Connecticut, and New Haven, as William Robertson wrote in 1796,

“entered into a league of perpetual confederacy, offensive and defensive; an idea familiar to several leading men in the colonies, as it was framed in imitation of the famous bond of union among the Dutch provinces [the Union of Utrecht, 1579], in whose dominions the Brownists [i.e. the Pilgrims] had long resided. It was stipulated, that the confederates should henceforth be distinguished by the name of the United Colonies of New England; that each colony should remain separate and distinct, and have exclusive jurisdiction within its own territory, that in every war offensive or defensive each of the confederates shall furnish its quota of men, provisions, and money … in proportion to the number of people in each settlement.”

The name "United States of America" called attention to the parallel with the independent Dutch

John Quincy Adams said that “The New England confederacy of 1643 was the model and prototype of the North American confederacy of 1774.” The name “United States of America” called attention to the parallel with the independent Dutch, whose country at that time was known in English as the “United States.”

Edward Winslow and William Collier represented Plymouth Colony in the negotiations in 1643. Familiarity with the Union of Utrecht depended on the presence of its full text, in English, in the book cited by Bradford with such precision: Grimeston’s A Generall Historie of the Netherlands. No precedent for such a combination could be found in English law. New England relied on the Dutch. This clearly contradicts the current fashion to imagine that the American federal system is derived from and inspired by the influence of the Iroquois Confederacy, a notion excellently demolished by Philip A. Levy.

Cromwell’s government

In 1646, Winslow arrived in London to defend against Samuel Gorton’s attempts to arouse resistance to the churches and governments of the New England colonies, especially Massachusetts Bay (but not including Rhode Island). Gorton had been granted permission to settle at Narragansett Bay by the Earl of Warwick and the Commissioners for Foreign Plantations, who denied that that territory fell under the jurisdiction of Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Gorton and Winslow both published books defending their respective claims. Winslow for the first time suggested that the colonies would be better off if independent from London. His other activities included the establishment of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England. Winslow rose to important positions within the committee system that formed the national government under Oliver Cromwell. He was appointed to supervise locating and confiscating property from royalists. Winslow was even among the officials tasked with inventorying and disposing of the king’s art collections at Westminster Palace, Hampton Court, Windsor Castle, and Greenwich.

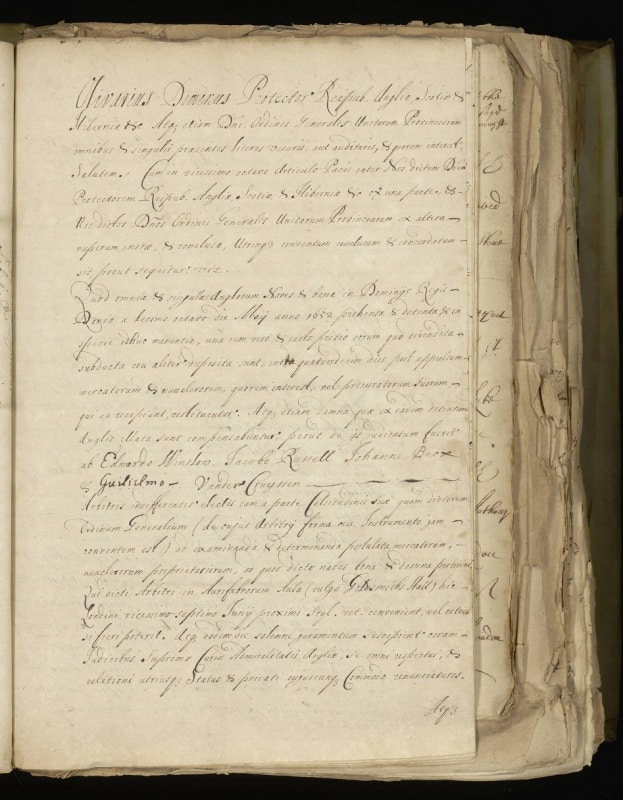

The appointment of Edward Winslow and others as arbitrators, 26 April/6 May 1654

The appointment of Edward Winslow and others as arbitrators, 26 April/6 May 1654© National Archives of the Netherlands

When war broke out between The Netherlands and England in May, 1652, Winslow participated in the government’s consideration of the idea that New England provide tar, hemp, and masts for the Commonwealth’s navy, to offset the confiscation by the Dutch of twenty-two English ships carrying tar and hemp from the Baltic. Winslow continued to advise and take other action in the government committees during the war, while keeping up his efforts for the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England.

When the war came to an end, a final detail was the appointment of an international committee of arbitration to settle the claims arising from the Dutch having confiscated the English ships, then in Copenhagen. The Dutch proposed that each side nominate two members. Edward Winslow and James Russell represented England; John Becx and Willem van der Cruyssen were the Dutch. All four had experience in New England.

Edward Winslow’s appointment is specifically mentioned in what is now known as the Treaty of Westminster, published on April 26/May 6, 1654. Winslow’s commission is in the collections of the Pilgrim Society and is displayed in Pilgrim Hall, at Plymouth, Massachusetts. The appointment came jointly from Cromwell and from the States General of the United Provinces. Damage to that document, rendering some words illegible, could be completed by comparison with the text in copies discovered in the Nationaal Archief in The Hague, where additionally all the minutes and correspondence of that international arbitration committee have been preserved.

Governor-designate

Winslow was thus esteemed at the highest levels of government both in England and The Netherlands, successfully managing the complexity of resolving the outstanding differences between them on a major point remaining at the end of the First Anglo-Dutch War. In the last year remaining to him, Winslow continued his involvement with New England matters that required government intervention. He was appointed a judge on the new special High Court of Justice for trying cases of treason. In 1655, he was appointed to be the civil governor of the colony that was to be established when England captured Jamaica. He died on May 8, in sight of the island but before the English capture. Winslow was buried at sea.

A final question remains, for which I have no answer: given the importance of civil marriage and the separation of church and state, the importance of the Union of Utrecht as a source for the federal system that developed later in America, and the novelty of an international arbitration committee to settle differences between The Netherlands and England, why do we find no information about the Pilgrims and Plymouth Colony in a book described as a ‘standard reference work on Dutch-American relations’ – Four Centuries of Dutch-American Relations, 1609-2009?

This article was originally published on the website of the National Archives of the Netherlands.

Further Reading

- Bangs, Jeremy D., Pilgrim Edward Winslow, New England’s First International Diplomat (Boston: New England Historic Genealogy Society, 2004).

- Bangs, Jeremy D., New Light on the Old Colony, Plymouth, the Dutch Context of Toleration, and Patterns of Pilgrim Commemoration (Leiden: Brill, 2020).

- Krabbendam, Hans, Cornelis A. van Minnen and Giles Scott-Smith (eds.), Four Centuries of Dutch-American Relations 1609-2009 (Amsterdam: Boom, 2009), described as “a handbook and standard reference work”.

- Levy, Philip A., “Exemplars of Taking Liberties: The Iroquois Influence Thesis and the Problem of Evidence,” William and Mary Quarterly, 1996, pp. 588-604.

Sources

- National Archives of the Netherlands, collection 1.01.02, inv. nr. 8484. Appendices to the report of the deputies to the peace negotiations between England and the Dutch Republic, 1653-1654.

- National Archives of the Netherlands, collection 1.01.02, inv. nr. 5484, Admiralty files, 1620.