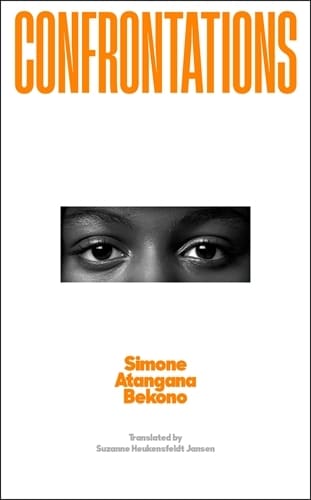

Hitting Back. ‘Confrontations’ by Simone Atangana Bekono

After her well-received poetry collection hoe de eerste vonken zichtbaar waren, the Dutch author Simone Atangana Bekono wrote her debut novel Confrontations

in 2020. Four years later, an English edition has now been published. Themes like racism return in this book, but why was poetic language given so little space this time?

In 2016, a manuscript circulated in the Dutch poetry world. It was a PDF of hoe de eerste vonken zichtbaar waren, a thesis project by a young poet that contained practically everything people craved at the time: poetry that was both political and personal, experimental verses full of direct, idiosyncratic one-liners like ik ben een plas bloed die door een kleed heensijpelt / en van systemen tekst probeert te maken – “I am a pool of blood that seeps through a cloth / tries turning systems into text”. And the poems all centered on the experiences of a young woman of color.

Simone Atangana Bekono

Simone Atangana BekonoDue to overwhelming interest, the work was published one year later as a slim collection of poems. The book was soon awarded the Poetry Debut Award Aan Zee. And so Simone Atangana Bekono (b. 1991), seemingly without ever really trying to, went from a recent graduate in her early twenties to one of the most promising young writers in the Dutch language area.

Four years after the poems, her debut novel Confrontations was published. In terms of theme, this book is an extension of the poetry collection: both texts can be read (among other things) as critical reflections on racism. About a quarter of the way through the poetry book, the reader encounters these devastating lines:

Alle zwarte mensen identificeren zich met gebroken mensen

alle zwarte mensen identificeren zich met verlaten mensen

alle zwarte mensen zijn crimineel

“All black people identify with broken people

all black people identify with abandoned people

all black people are criminals”

Crime and abandonment return to the fore in Confrontations. The novel revolves around Salomé Atabong, a sixteen-year-old student at a gymnasium school somewhere in the south of the Netherlands. As an introverted black girl, she has been an outsider from the first day of school. Over the years, she has been increasingly bullied. Until, at her father’s advice, one day she hits back. A brawl ensues, escalating to the point that Salomé is placed in a juvenile detention centre for six months.

The novel begins with Salomé’s arrival at this institution and, apart from a few flashbacks, also largely takes place there. The Donut, as this roundhouse of detention is called, is described almost sociologically – and according to the list of interviewees thanked in the acknowledgements, the writer had done her research.

With incredible precision, Atangana Bekono sketches the suffocating microcosm in the institution

With incredible precision, Atangana Bekono sketches this suffocating microcosm in which tormented young women have it out for each other, while also seeking each other out to combat the loneliness. They are disciplined and sometimes humiliated by gruff men, and the organization is headed by a man once known for uttering racist slurs on the dismal TV show Hello Jungle – a suboptimal track record for the warden of this diverse group.

The experience in this harsh environment is told from Salomés’s perspective. She undergoes the compulsory program resignedly, tries to avoid conflict and resolutely holds psychologists and coaches at arm’s length. When Salomé is alone in her all-white cell, she reads books: Ernest Hemingway, Albert Camus, Jan Wolkers, W.F. Hermans, Toni Morrison. Besides her family, she seems to miss Dutch classes in particular: literature offers Salomé a temporary escape from her own existence, peace. At other times she is “explosive” or depressed. And although Salomé herself says she is “unwell”, it is almost impossible to separate her despair from the misery she experienced growing up: a terminally ill father, confusing family visits in Cameroon, loneliness, constant bullying, violent racism. Her temperament and social background may be different from that of the other detainees, but she still had to endure a lot.

Despite the authentic subject matter and pressing themes, the story does not come to life

Throughout the book, Salomé speaks in the same slang we hear from her fellow sufferers, for whom she often musters a great deal of empathy: “We all watch Two Weeks Notice together. Being honest the movie isn’t even that shit. But Marissa is a bloody idiot. I been like that. I seen other people be like that too. Sometimes we just go crazy hitting and cursing and being like that.”

In the sheltered but gruelling daily rhythm of the Donut, Salomé tries to figure out how her life could have turned out like this. She thinks back to her family, the racism inflicted upon her Cameroonian father, the village bullies, and the pivotal moment when she lashed out. But all that grinding yields bitterly little. In the end, Salomé comes to the unelevating conclusion that the “why” is simply unanswerable: “My opportunity to answer that question has passed, it has expired.”

Because you already know what Salomé has done from the start, and she herself does not come up with any surprising insights, Confrontations lacks tension. A large part of the novel consists of an accumulation of scenes from the juvenile detention centre, which fail to make any meaningful connections. Despite the authentic subject matter and pressing themes, the story does not come to life: the characters remain anonymous, their inner lives are vague, and the narration without real development feels directionless. And although Salomé has indeed acquired a recognizable voice of her own, the language itself offers little reprieve: the style is often remarkably neutral, as if the poetic bravura from hoe de eerste vonken zichtbaar waren has been scrubbed out by an editor.

But there are two passages in which this tenor is broken. First, the final description of the fateful battle is so feverish that the syntax is utterly jettisoned. And a second, dark dream vision about resentful Furies attains a similar linguistic intensity:

Samen komen ze op me af en het veld waarover ze vliegen verdort onder het klapwieken van hun vleugels. Alles achter ze is dor, dood, fikt af in een enorme, likkende brand: de vogels vallen vonkend naar beneden en de bomen exploderen tot wolken van as. Ze zijn woest op mij. Ze willen me gek maken. Ze willen me dood, dood als de vallende vogels, dood als de gillende insecten, de panikerende dieren die doodbranden in het bos. Het krijsen doet het glas barsten van de ruimte waarin ik sta.

“Together they come at me and the field over which they fly withers with the flapping of their wings. Everything behind them is barren, dead, burning in an enormous, licking fire: the birds fall sparkling to the ground and the trees explode into clouds of ash. They are furious with me. They want to drive me crazy. They want me dead, dead like the falling birds, dead like the screaming insects, the panicked animals burning to death in the woods. The screeching shatters the glass of the room in which I stand.”

Here the language begins to soar and move. Here the poet in Simone Atangana Bekono speaks again. What a pity this side of her was given so little space in Confrontations.

Simone Atangana Bekono, Confrontations, Serpent’s Tail, London 2024, 192 pages

This text is a translation of a slightly modified review of the book originally published in Dutch.