Migration Across the North Sea Was Once Seen as a Solution — Why Is It No Longer Considered One Now?

The United Kingdom’s tough migration policy makes the North Sea a particularly dangerous crossing route, but until the nineteenth century, the country was known as a liberal haven for people who could not find a home anywhere else. That policy changed quickly, at least partially, after a diplomatic discussion in which Belgium played a leading role. Since then, migration has been seen mainly as a social problem that has to be solved.

The English Channel, connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the North Sea, is one of the busiest maritime routes in the world. Small rubber boats carrying migrants, who cross from Calais to Great Britain, must make their way amongst the freight, business, and tourist traffic. Despite frantic efforts by the French and British police to discourage crossings, the numbers are increasing exponentially: until 2020, the United Kingdom registered fewer than 10,000 migrants crossing the Channel, but, in 2022, no fewer than 45,755 migrants washed ashore. At least 64 people have lost their lives in the past six years.

But even those who survive the perilous journey have few guarantees upon arrival. It seems more likely every day that migrants from the United Kingdom will be sent on to Rwanda. To secure this policy, the British government concluded a controversial treaty at the end of December 2023. People who enter England illegally can be sent to Rwanda to have their asylum applications processed there. If these are not approved, the migrants will have to start a procedure to either stay in Rwanda – or apply for asylum elsewhere. The hundreds of millions of pounds the UK will spend on this deal are being pitched as an investment that will pay for itself in the long term by discouraging migration.

In 2022, no fewer than 45,755 migrants washed ashore. At least 64 people have lost their lives in the past six years.

In 2022, no fewer than 45,755 migrants washed ashore. At least 64 people have lost their lives in the past six years.© Mika Baumeister / Unsplash

Unfortunately, the short-sightedness of such an approach is underlined every day by the tragedy that is taking place in and around the Mediterranean Sea. Rather than discouraging migrants – many of whom are legitimate refugees – from setting sail, the policy forces them to take increasingly dangerous routes. At least 29,000 migrants have drowned in the Mediterranean since 2014. During the journey, they also fall prey more easily to criminal intermediaries who charge as much as 2,000 euros for the crossing. And it is Belgium, rather than France, that is more often the starting point. This shows that the approach only shifts the problem in a different direction. It does not offer a structural solution.

The United Kingdom, once celebrated as a haven for migrants and refugees, has a particularly restrictive migration policy today. However, the seeds for that policy were sown much earlier.

The Channel as a highway

In the mid-nineteenth century, liberalism was at its height in Europe – including in the field of human mobility. The United Kingdom was the standard bearer: entrepreneurs, civil servants, and labourers traveled to all corners of the empire and beyond to support its expansion. Many did not return – around 10 million emigrated from the UK alone. They did this partly at the expense of the state, which also worked to keep the administrative barriers to immigration as low as possible.

The United Kingdom has a particularly restrictive migration policy today. However, the seeds for that policy were sown much earlier.

This open-door policy also went in the opposite direction: foreigners who settled in England did not need a passport, an approach that was also followed elsewhere in Europe. Identity checks at most European land borders were suspended. At that time, migration was not seen as a problem but as a solution, for example by reallocating labour according to supply and demand or by channeling dissidents.

Propelled by steam technology, international mobility, via the Channel and especially via Belgium, increased. To consolidate its independence, the young Belgian state was resolutely committed to the development of modern transport networks. The reasoning was that the more other countries became dependent on Belgium’s transport network for their trade, mobility and communication, the more likely they would be to defend Belgium’s right to exist.

Following the example of England, Belgium pioneered the development of railway connections on the European mainland. Due to tense relations with the Netherlands, the rail network focused on Germany, France and England. Fast steam connections were considered an extension of the rail network. The port of Antwerp opened steam shipping services worldwide, but it was the Channel service between Ostend and Dover that flourished as a hub for passenger transport between England and the continent. From the mid-1840s onward, both Belgian and British steamship services provided daily connections between the two ports.

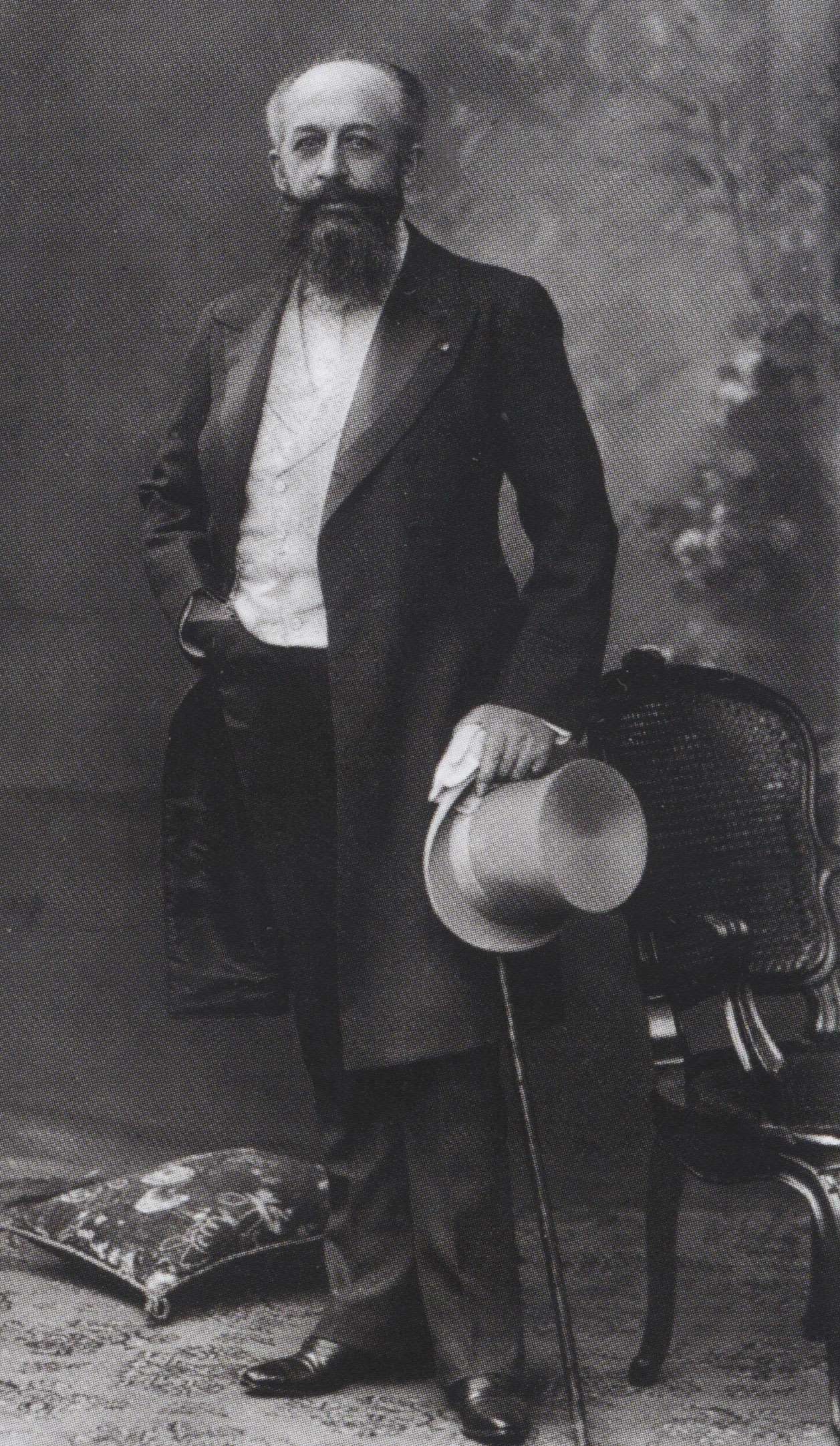

Belgian engineer Georges Lambert Casimir Nagelmackers

Belgian engineer Georges Lambert Casimir Nagelmackers© Gaspard-Félix Tournachon / Wikipedia

These connections facilitated business travel, but also tourism. The fact that Ostend developed into a popular seaside resort was partly due to the British. For them, the Belgian coast was a cheaper alternative than seaside resorts in their own country, and good transport links made the Belgian coast easily accessible. Germans, Russians and the French also quickly found their way to Belgium where, in the summer, they mixed with the Belgian beau monde, from which all manner of (business) relationships and initiatives emerged.

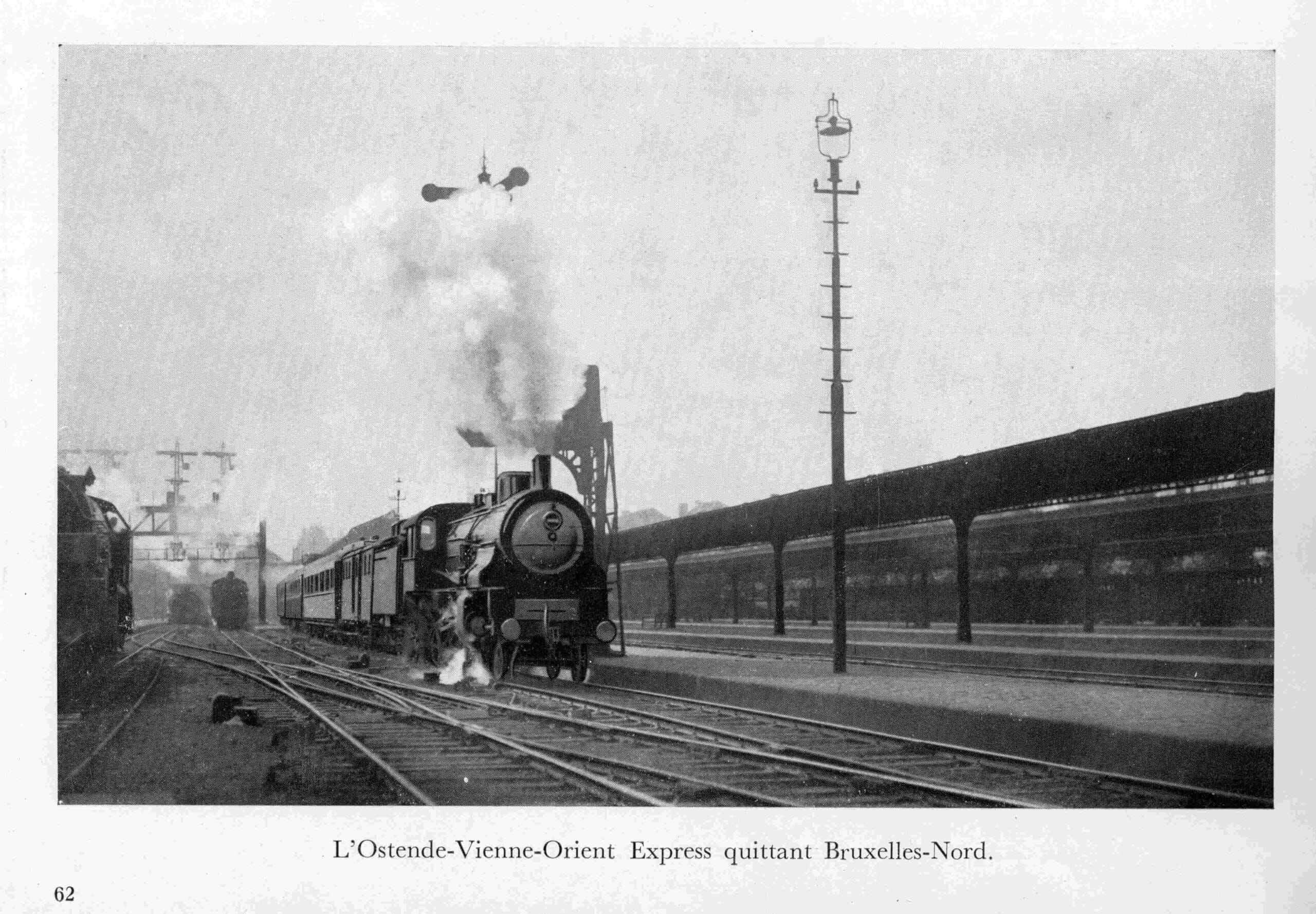

Ostend played an important role in the development of the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits, the brainchild of the Belgian engineer Georges Nagelmackers. The railway company provided luxurious sleeping carriages for long-distance routes between European cities and beyond, including the famous Orient Express. Various other routes, such as the Vienna Express and the Suisse Express, called at Ostend. Cross-Channel connections ensured that Great Britain was included in the network. These transport links served business travelers and tourists, but migrants were also able to benefit from well-developed transport networks. The various categories of travelers made it increasingly difficult to distinguish one from another, which made migration controls more difficult.

Suspicion

The fact that mobility across borders was relatively easy did not mean that foreigners could simply settle anywhere. Migration controls still came into play, but they took place inland rather than at the border. Belgium was also a forerunner in this. Immediately after its creation in 1830, Belgium was the first country in Europe to establish an immigration police force, mainly because the Belgians were suspicious of dissidents and foreign influences that could potentially threaten its independence.

The Ostend–Vienna Orient Express departs from Gare du Nord in Brussels, circa 1925

The Ostend–Vienna Orient Express departs from Gare du Nord in Brussels, circa 1925© The International Publishing Corporation, S.A. Bruxelles / Wikipedia

The central immigration agency soon expanded its power to control all foreigners in the country. The main goal was to deport poor people and criminals. Travelers who stayed in the country for less than two weeks had to register in the so-called accommodation registers. Anyone who wanted to reside in the country for a longer period of time had to register via an extensive alien processing system managed by local police departments.

The immigration police checked whether the person appeared on lists of undesirables and increasingly began to systematically request information about his or her personal history and behaviour in previous places of residence, as well as the birthplace. Even after the abolition of the passport requirement, foreigners still had to present an identity document to register.

The organisation knew well enough that the system was far from watertight, and therefore also relied on other sources of information. Correctional courts, gendarmes, prison and hospital directors had to send extensive reports when interacting with foreigners. Furthermore, the immigration police also collected information on an ad hoc basis, for example, through newspapers or citizens who reported foreigners.

Belgium was the first country in Europe to establish an immigration police force

This parallel administrative world allowed the deportation of so-called ‘undesirables’ from the country. The immigration police had broad decision-making powers to deport individuals from the country, regardless of their length of stay. And, of course, the officials could also count on a well-oiled transport network for this. Special train wagons ran at least weekly to the seven most important national borders, such as Essen and Lanaken, for deportees with the Netherlands as their destination. By the end of the nineteenth century, more than ten thousand poor people or criminals were being deported every year. The fact that there was no initial identity check at the border did not change the workings of the system very much.

Diplomatic riot

Some of the undesirables were given the opportunity to leave of their own volition but the majority were escorted by the gendarmerie. Initially, they could choose which border they were sent to – a measure at least served to protect deserters and political refugees. This principle came under some pressure in the 1880s due to protests from neighbouring countries, but it was partly preserved.

The biggest problem with the system was that deportees could easily return and were increasingly sent back by neighboring countries. That is why the immigration police resorted to a slightly more expensive but longer-lasting solution for problem cases: sending them across the Channel. Well-known examples of dissidents who eventually settled in England via Belgium are Karl Marx and Victor Hugo.

Much less known are the stories of thousands of others who were forwarded like so many parcels by the immigration police, whether or not through their own means, such as Edward McLean. At the end of August 1895, McLean registered under the name of George Hamilton in the lodging register of the Hotel de Londres in Ostend. Shortly afterwards he was arrested for theft and identity fraud. Thanks to the work of Scotland Yard, the alleged Englishman was exposed as a wanted American thief and sentenced to a year in prison in Bruges.

After serving his sentence, McLean was deported. Lacking the funds to travel back to the United States, he chose England as his destination. The immigration police arranged a secret escort with the gendarmerie and the maritime police, allowing him to board the packet boat in Ostend as discreetly as possible. Suspicion among fellow passengers and the English authorities had to be avoided, because Belgium and the United Kingdom had officially agreed in 1894 to only deport nationals to each other.

But McLean was intercepted in Dover by English agents. The arrest caused a diplomatic row: Belgium had violated the agreement by sending a non-British deportee. Moreover, he was a notorious criminal. However, even after the scandal of the McLean case died down, the immigration police continued to deport certain problem cases – such as stranded sailors, English speakers and citizens of British colonies – via the Channel. And those who could finance the crossing themselves were not in any way discouraged from traveling to England by the Belgian immigration police.

Lock on the door

England was favoured as a deportation point by the Belgian authorities because the entry and residence of foreigners was barely controlled there. The risk of being re-deported was also negligible compared to other countries. Yet immigration into England remained relatively limited, especially in relation to the multitude of Britons who emigrated during that period.

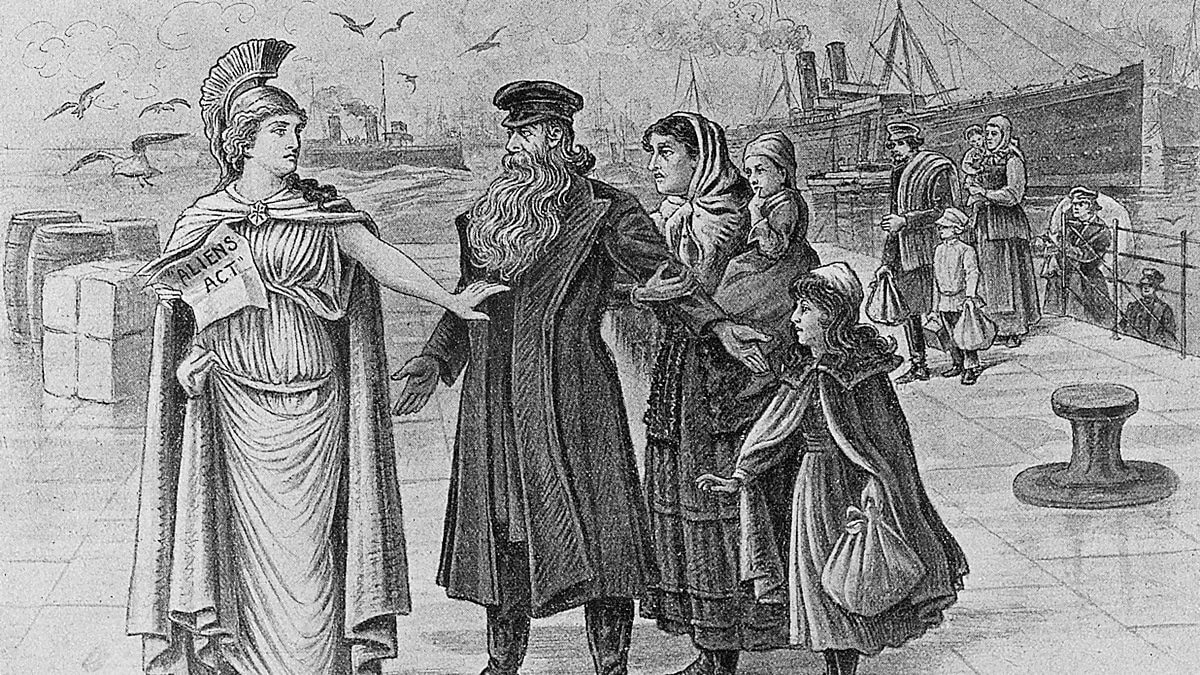

This is not to say, however, that migrants were welcomed with open arms. The largest immigrant communities, the Irish and Eastern European Jews, were considered inferior. That stigmatization, together with the number of foreigners on poor relief and in prisons, fueled the debates that led to the so-called Aliens Act of 1905.

Cartoon from 1905 about the newly introduced Aliens Act, in which Britannia says: 'I can no longer provide shelter to refugees. England is not a free country.'

Cartoon from 1905 about the newly introduced Aliens Act, in which Britannia says: 'I can no longer provide shelter to refugees. England is not a free country.'© Jewish Museum London

That Act gave British customs officers the right to ban criminals, the poor and the sick upon arrival. Such inspections remained limited in practice, but they did lay the foundation for an extensive inspection system that would be further expanded during the First World War. From then on, foreigners were monitored before their departure, at the borders and during their stay. The controls and legislation were intended to prevent England from serving as a haven for unwanted aliens from other European countries. The McLean case suggests, however, that inspections at some ports were taking place even before the Aliens Act. Channeling unwanted people to neighbouring countries rather than to their home countries was often easier and cheaper.

Because the Belgian immigration police stuck to this practice, problem cases were simply shifted from one place to another, rather than dealt with. This undermined any faith in international agreements and intensified calls for national solutions. During the First World War, the British government tightened its control over foreigners. From then on, migration was pushed further into illegality and became increasingly problematic and dehumanising.

The legislative framework was limited and vague during the nineteenth century. It gave the Belgian authorities leeway to deport undesirables from the country almost without hindrance. Foreigners were stigmatized, but given a chance to settle. Because checks took place inland, migrants were not burdened with additional costs or risks along the way. They could also immediately integrate into the labor market to earn a living, which meant that this was a low-cost, revenue-producing process for the state. Migration was relatively self-regulating and offered solutions for imbalances in labor markets, for the adventurous urge for the unknown, etc. Migration was primarily a solution and not a problem.

Providing refugees with a temporary new home as quickly as possible benefits those affected, but also society-at-large

Migration was primarily a solution and not a problem.

Migration can still be a solution today, for example, to compensate for the many shortages in the labor market. Or, migration can become a symbol of human solidarity, such as the massive aid to Ukrainians with support in the country of origin, in transit and also upon arrival. The United Kingdom took in more than 200,000 Ukrainians and defined policies to shelter them as quickly as possible. Why can’t the UK do that for Afghans, Sudanese or Syrians?

Providing refugees with a temporary new home as quickly as possible benefits those affected, but also society at large. As part of the host society, a migrant can contribute more. But how can we expect a similar contribution if we force people to travel for months or years, exposing them to trauma, danger and permanent exploitation, in order to throw them, once all possible means are exhausted, into long, uncertain and freedom-restricting procedures upon arrival? A postcard with greetings from Rwanda?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.