Draining and Building: The Dutch in the Baltic Sea Region

It is well known that at the end of the seventeenth century Peter the Great spent several years in Holland learning techniques such as shipbuilding in order to modernize the Russian Empire, but since the Middle Ages many people from the Low Countries have been going the other way, often settling in towns on the Baltic coast or along the rivers that flow into the Baltic. Their presence is still visible and audible today.

In the Middle Ages, it was typically merchants of the Hanseatic league who would visit towns along the Baltic coast, such as Gdańsk (German Danzig) or Lübeck in order to trade. However, in the sixteenth century in the wake of the Protestant Reformation, others left the Low Countries for this region for religious reasons.

Menno Simons (1496-1561)

Menno Simons (1496-1561)One group who left were the Mennonites. There was a Mennonite community in Danzig from the sixteenth century until at least the middle of the eighteenth century, with sermons being given in Dutch. Indeed, in 1549 the founder of the movement, Menno Simons, began to organize the growing Mennonite community in Danzig into a congregation. It is not surprising that Frisian names are found in the church records, for Menno was from Frisia. However, there were also Flemish as well as Dutch names in the records. One historian has argued that the Dutch language, or varieties thereof, continued to be spoken at home into the eighteenth century by members of this group.

‘Holland’ wind mill at Straupitz

‘Holland’ wind mill at Straupitz© Blumenbiene

Others emigrated from the Low Countries to what is now Poland, too. For obvious reasons, the Dutch have long been experts in draining marshy land. In England the Dutch drainage engineer, Sir Cornelis Vermuyden, led teams of migrants from the Low Countries to drain land in Essex, the Fens and the Lincolnshire/Yorkshire border. The Dutch River in Lincolnshire is one toponym that bears testimony to Vermuyden’s work. In Poland in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, people from the Low Countries migrated to the area around Danzig and the marshy areas along the River Vistula (Wisła

in Polish). Nowadays, 54 settlements have ‘holender’ or a variant thereof in their toponyms, a number which was much larger in the past. It is also reckoned that more than 4,000 Poles have the surname, ‘Olender’.

Adjacent to Poland is the Upper Spree region in Brandenburg in Germany. It has been suggested that drainage workers from the Low Countries moved there in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in order to assist with draining this marshy area. One physical, although by no means, conclusive, piece of evidence for the Dutch presence is a ‘Holland’ wind mill at Straupitz (Tšupc in the local Sorbian language) near Cottbus. This was built in the early nineteenth century, replacing an earlier mill from the seventeenth century.

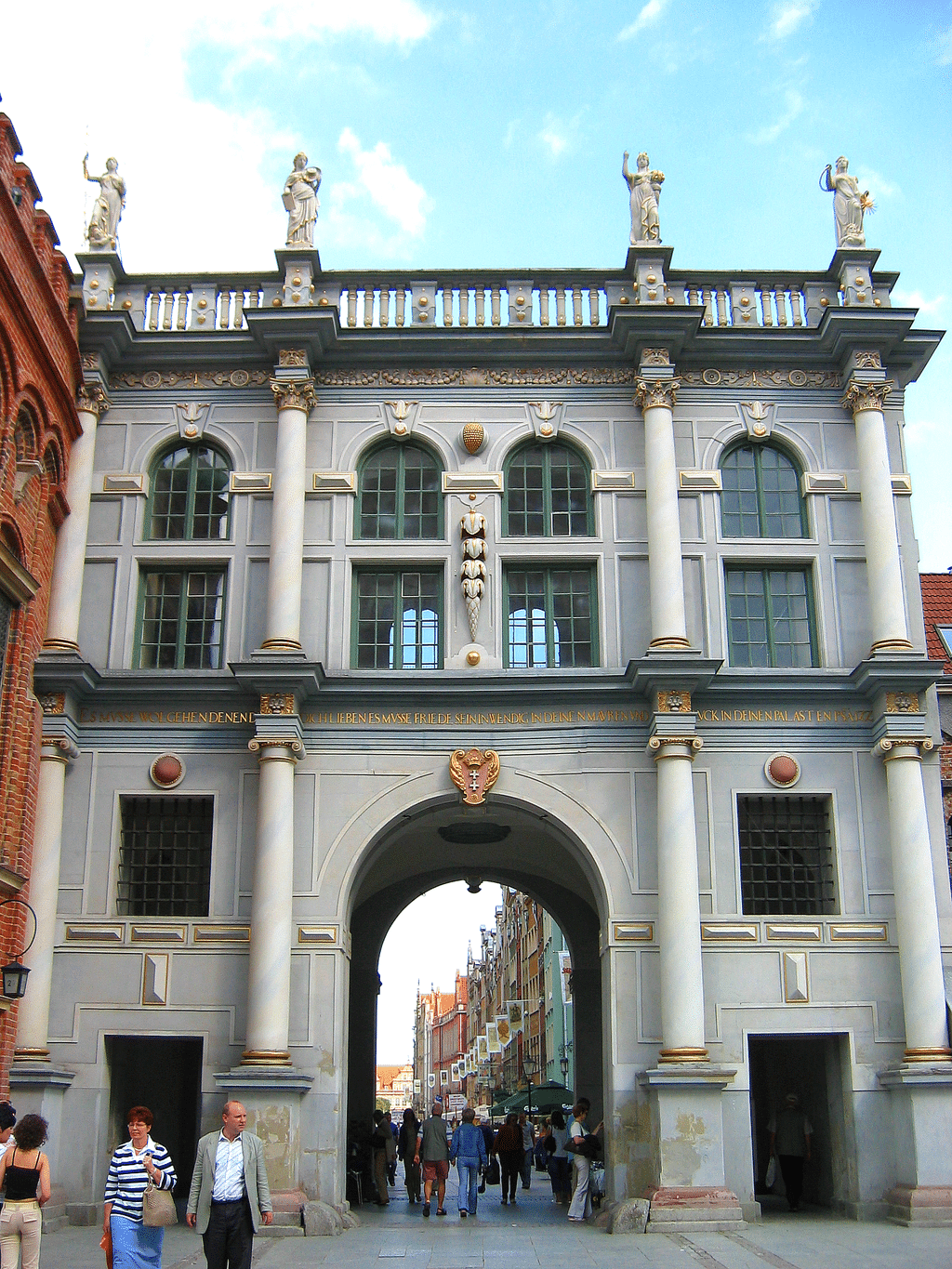

Golden Gate in Danzig

Golden Gate in Danzig© Maciej Szczepańczyk

Other Dutch technical skills also were in demand. For example, Abraham van den Blocke, whose parents had moved to the Baltic region from Flanders, designed the imposing Golden Gate (Złota Brama in Polish) in the centre of Danzig in 1612-1614. The Fleming Anthonis van Obbergen designed important buildings in Denmark before moving to Danzig where along with Van den Blocke and a Polish architect, he designed the Old Arsenal in Danzig. Van den Blocke became a citizen of Danzig and both he and Van Obbergen died in the city. Along the Baltic coast in Rostock the Dutch engineer Johan van Valckenburgh improved the town’s fortifications.

Although Dutch connections with Russia were typically related to trade and did not involve permanent settlement, clearly some people from the Low Countries did settle in Russian towns. There were Dutch trading posts in several Russian towns and with these came church communities.

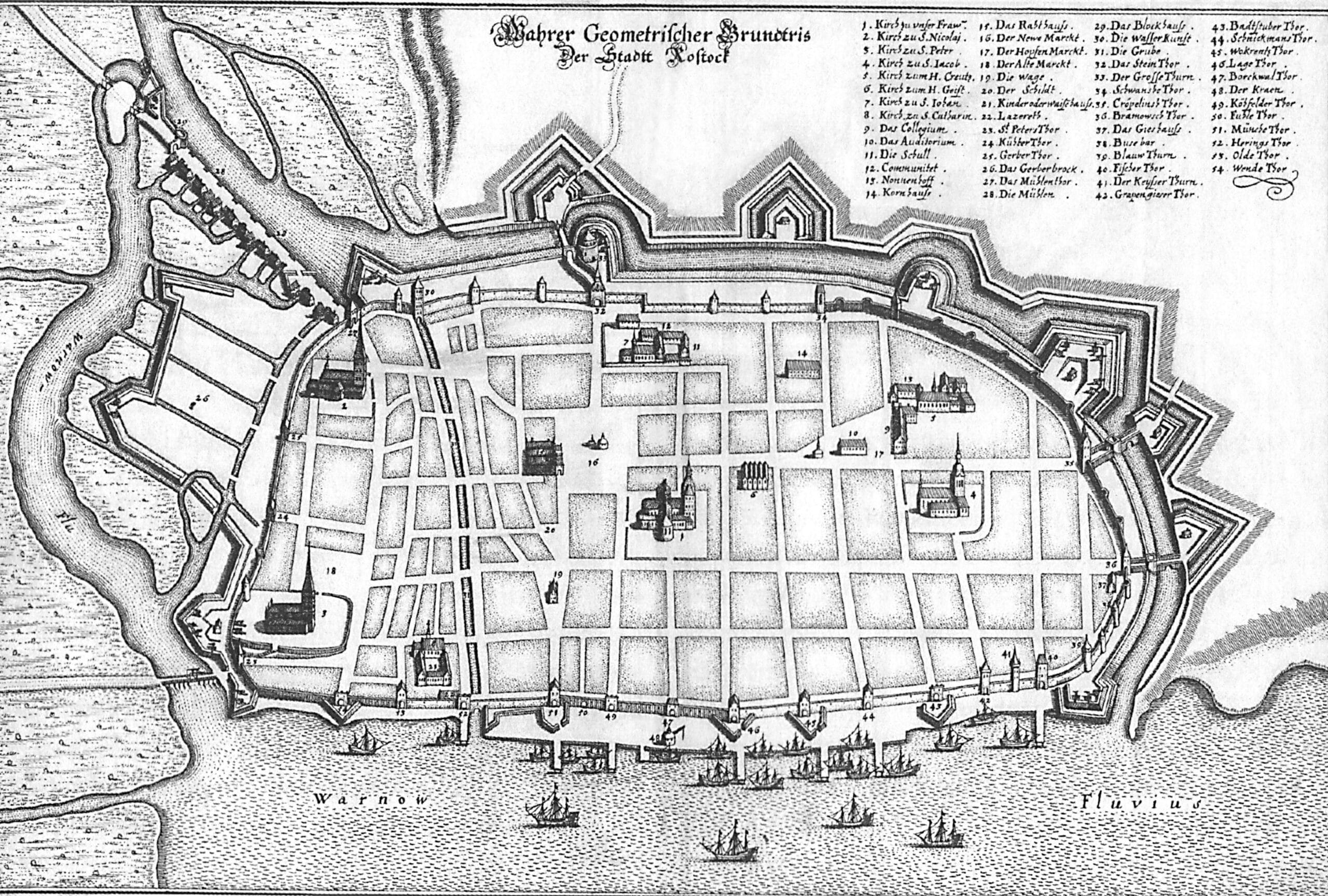

Johan van Valckenbrugh's plan for the fortifications of Rostock in 1624

Johan van Valckenbrugh's plan for the fortifications of Rostock in 1624From the early seventeenth century Dutch church communities met for worship in Moscow and in St. Petersburg, shortly after its founding in 1717, and even on the Russian Arctic coast in Archangel from about 1635. Drainage workers were invited to settle in Denmark and traders and engineers established themselves in Sweden. We should not forget that Sweden’s second city, Gothenburg, was founded as a Dutch trading colony in the early seventeenth century.

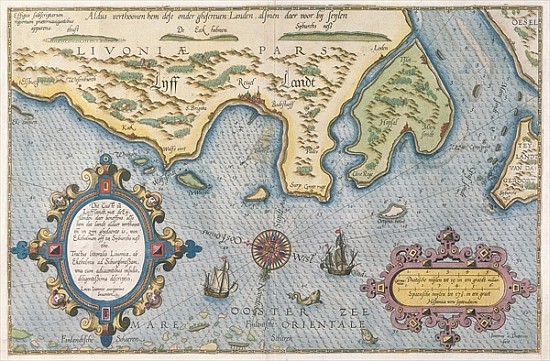

Dutch Trade map of the Baltic Sea

Dutch Trade map of the Baltic SeaOne consequence of the Dutch presence in the Baltic was that the Dutch language became the lingua franca in the region in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Swedish monarchs knew some Dutch, diplomatic correspondence was sometimes written in Dutch and Dutch learning materials and dictionaries were in demand. One of the inaugural lectures of the Royal Academy of Åbo, then in Sweden, now in Finland, was given in Dutch. Dutch was also used in the military. In peace negotiations between Russia and Sweden in 1618, the Englishman John Merrick wrote to the Field Marshal of Swedish troops in Russia…in Dutch.

Peter the Great, Portrait by Paul Delaroche, 1838

Peter the Great, Portrait by Paul Delaroche, 1838Given this migration, trading and political and military activity, it is then no surprise that many Dutch loanwords can be found in languages spoken in the Baltic region. In building St. Petersburg and a Russian navy, Peter the Great employed a significant number of Dutchmen. As a consequence many terms to do with seafaring in Russian, such as the Russian for ‘skipper’ and ‘sailor’, come from Dutch. In fact the etymologist Nicoline van der Sijs reckons that there are some 500 Dutch loanwords in regular use in Russian. Danish and Swedish have both adopted over 2,000 Dutch loanwords. Many of these have to do with trade and seafaring, but a Dutch loanword in Swedish such as doolhof (maze, dollhof in Swedish) illustrates that this is not the whole story. Finnish has some 50 Dutch loanwords, mainly via Swedish, as the latter was the language of culture for many years in Finland. For example, the Dutch word for sailor, matroos, has entered standard Finnish as matruusi, denoting an experienced sailor. The standard Finnish word for the captain of a ship is kapteeni, while in spoken Finnish the word kippari is used. This, it turns out, is derived from the Dutch schipper, a word which like matroos has been loaned to many languages. Finally, it is reckoned that there are at least 370 Dutch loanwords in Polish. However, some of these may derive from varieties of Low German (Nedersaksisch), spoken from the West of the Low Countries as far as present-day Western Poland, and used as a lingua franca in the Hanseatic League. Many of the Dutch loanwords in Polish, loaned directly or indirectly, relate to seafaring. These include harpun (harpoon), kielwater

(ship’s wake), maszt (mast), szyper (skipper) and kooi

(hammock). However, other loan words not related to seafaring such as lakmus

(litmus) from the Dutch lakmoes and makler (broker) from the Dutch makelaar illustrate that the influence of Dutch on Polish is broader than this.

In conclusion, then we can see that through migration, for religious and economic reasons, and trade, which sometimes involved permanent settlement in other countries, the Dutch and Flemish and their language have had a significant influence on the cultural, linguistic and indeed physical landscape of countries surrounding the Baltic Sea.