Boers and Creoloid: The Legacy of Dutch Migration to South Africa

It is well known that many South Africans can trace their roots back to the Low Countries and that the Afrikaans language is closely related to Dutch, but how is it that a land so far away and different in so many ways has such close links to the Low Countries?

For the answer to this question we have to go back to the seventeenth century, when hundreds of ships under the flag of the Dutch East India Company sailed from ports in the Dutch United Provinces to East Asia, above all to profit from the spice trade. Although the VOC made vast sums of money, sailing to East Asia was dangerous and difficult with as many as one in four ships not reaching their destination. In order to provide a safe haven on this long journey and a place where ships could take on fresh water and food, in 1652 an expedition led by Jan van Riebeeck set out to establish a harbour of refuge at the Cape of Good Hope on the southern tip of the African continent.

Jan van Riebeeck arrives in Table Bay in April 1652, painting by Charles Bell

Jan van Riebeeck arrives in Table Bay in April 1652, painting by Charles BellWithin a few decades a permanent Dutch settlement or colony had become established by the Cape, populated by former VOC employees. As the VOC was a multinational organization, it was not only Dutch but also other Europeans such as Germans and Scandinavians who settled there. They were given land to farm, although in due course they took over the land of local tribes such as the Khoikhoi. In 1685, the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes meant that many Protestants had to leave France. Several hundred moved to the Cape Colony, where they were welcomed by their co-religionists, the Dutch Calvinists. Intermarriage meant that we can talk of a European rather than simply a Dutch colony, although the settlers typically spoke a variety of Dutch.

Dutch fortress The Good Hope

Dutch fortress The Good HopePrecise figures are hard to come by, but it is reckoned that by the early eighteenth century there were over 600 VOC employees living in the Cape. By the end of the eighteenth century, this figure had risen to over 3,000, which accounted for about 10% of the overall population of some 30,000 in the Cape Colony. This number included soldiers drafted in to protect the colony, particularly from attacks by other European nations, incomers who farmed the land, and skilled artisans such as carpenters for ships and for the houses of the growing colony. While some employees had set out to travel to the Cape, others had intended to travel to East Asia, to VOC trading posts such as Batavia, but they had been too sick to continue their journey from the Cape and settled there instead.

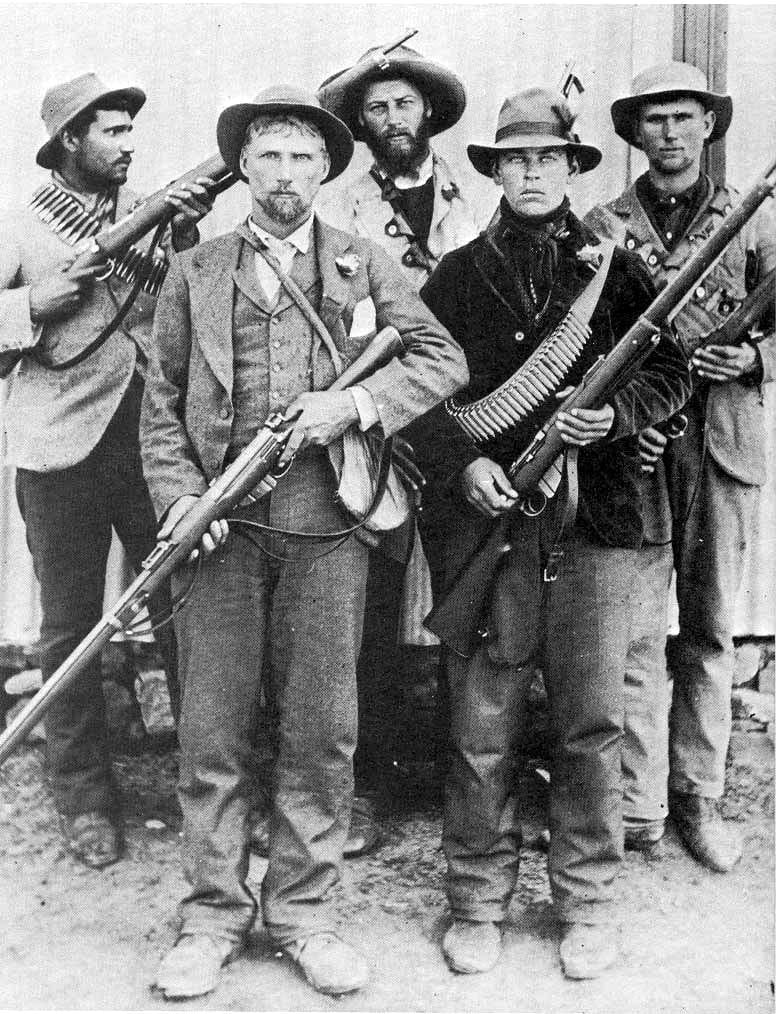

Boer wars

Boer guerrillas during the Second Boer War

Boer guerrillas during the Second Boer WarThe Colony’s fortunes changed dramatically as a result of the Napoleonic Wars. The VOC was declared bankrupt in 1799. In 1814, the Dutch government ceded the Cape Colony to the British and significant British migration to southern Africa followed. This resulted in the Great Trek, when thousands of people of Dutch heritage moved into the interior of Africa and formed the Boer Republics such as Transvaal and Orange Free State. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the British sought to take over these Republics, a move which led to the Boer Wars. In the Netherlands, there was much anti-British sentiment as a result of what the Dutch perceived to be an attack on their Boer brothers and sisters. The defeat of the Boers led to the incorporation of the Republics into the Union of South Africa. Some Boers migrated to other parts of the world, such as Patagonia in Argentina, where there is still an Afrikaans-speaking community. Today South Africa is an ethnically and culturally diverse country, where the descendants of the Dutch settlers form only a minority.

Creoloid

But what traces have they and their ancestors left in the modern South Africa? I have already mentioned the Afrikaans language. This has been described as ‘the only language of Germanic origin which is spoken exclusively outside Europe’ and the only still extant daughter language of Dutch, and it should not be forgotten that it has developed a rich literary tradition. Linguists refer to it as a ‘creoloid’, i.e. a variety of language that resembles a creole, but did not go through the stage of being a pidgin. At root it emerged from Dutch, but differs from it in important respects. It only has one gender for nouns, whereas standard Dutch has two, and the verb forms are much simpler. Most of the vocabulary can be traced back to varieties of Dutch, but it also includes words from other European languages and indeed indigenous southern African languages.

Afrikaans

AfrikaansA variety of Dutch different from that spoken in the Low Countries was, according to linguists, already emerging in the late seventeenth century. However, the ancestor of modern Afrikaans remained essentially a spoken language until the early twentieth century. In 1925, Afrikaans was legally recognized as an official language of South Africa. Today, it is reckoned that Afrikaans is the home language of some six to seven million South Africans. While many of these are descendants of the settlers from the Low Countries, the majority of Afrikaans speakers are non-white. Afrikaans is also spoken in neighbouring Namibia, which was mandated to South Africa after the First World War. Afrikaans is still spoken by some 60% of the white population in Namibia. Dutch and Afrikaans place names are still found across South Africa, from Kaapstad (Cape Town) and Stellenbosch in the Cape to Johannesburg and Bloemfontein in the interior.

Cape Dutch architecture

Cape Dutch architectureThe settlers from the Low Countries did not only bring their language with them. They also built their houses in styles influenced by those used in their homeland. Cape Dutch architecture is a distinctive style marked by its whitewashed walls and rounded gables. Academics have also identified a specific form of Cape Dutch furniture, typically made of exotic woods such as mahogany and attractive yet plain in appearance.

The descendants of the settlers have kept many of their traditions alive

As the name suggests, the Dutch Reformed Church (Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk) in South Africa owes its origins and predominantly Calvinist theology to the Reformed Church in the Netherlands. However, although the descendants of the settlers have kept many of their traditions alive, they have also borrowed from those around them. A good example of this is in the field of sport, where rugby union and cricket are probably the most popular sports among Afrikaners in South Africa. They were introduced to both sports by British settlers, and although both rugby union and cricket are played in the Low Countries, they are much less popular there than other team sports such as association football and hockey.

South African cricket player

South African cricket playerIn this article, I have not discussed the more problematic consequences of the settlement of Dutch and other Europeans in South Africa. They deserve a much more detailed study than is possible here. However, what I have tried to do is to illustrate that Dutch emigrants spread their wings to another part of the world and that although their descendants are but one of several ethnic groups in today’s South Africa, their cultural heritage still plays an important role in the life of this ‘rainbow nation’.