The Sea Is a Lover: The Healing and Imaginative Power of the North Sea

Inhale the fresh air on the beach, the scent of iodine, the taste of salt on the skin. The North Sea is a source of salty self-care for many people – especially women – which is nothing new. Two centuries ago, North Sea cures were mainly women’s cures, for what was called female ‘hysteria’. But what if bathing in salt water did not dampen feminine impetuosity, but rather celebrated it?

The healing power of water has been recognised throughout time and place. Myths, stories and, above all, science, have proven it. Consider the Egyptian god, Ra. In the morning, he rubs the sleep from his divine eyes and, as a morning ritual, throws water on his face to strengthen his immortality. Hippocrates, the ancient Greek physician, had slightly less ambitious intentions when he advised his patients to go into the sea in Adam’s costume. According to him, a refreshing dip would maintain the balance between the body’s four ‘humours’ – a balance essential for the mind and physical condition.

The idea that the sea can regulate our phlegmatic, passionate, melancholic, or choleric character has fallen out of fashion in medical circles. Yet Hippocrates’ thinking is still relevant. We suspect that baths, sea baths, and even ice cube dipping would be beneficial for us, not only for our bodies, but also for our morals – especially for those of us who are women.

We suspect that baths, sea baths and even ice cube dipping would be beneficial for us

A dive into the medico-historical and popular scientific sources in the Low Countries reveals that the North Sea cure was initially a medical therapy, particularly for treating hysteria. No surprise, then, that today the cool North Sea bath has grown into a kind of salty self-care for women. Contemporary, mostly female, authors see this special bond between women and the sea somewhat differently. Healing and health, as it will turn out, are not possible without imagination.

The medicinal power of a sea-cure bath

It is the mid-eighteenth century. Medicine is still in its infancy. The sea is less a place of fun than it is a wild and fierce natural element. And yet the practice of taking the waters becomes popular in Brightelmstone – later Brighton. The aristocratic ladies and gentlemen carefully venture into the sea. The men pray. The women, modestly covered from head to toe, immerse themselves, gallantly assisted by so-called dippers. Pots of fresh water are provided to douse the women afterwards; that salty water could damage their delicate complexions.

A certain Richard Russell, student of the Leiden physician Herman Boerhaave, wrote a bestseller in 1760 about the medicinal power of sea bathing: A Dissertation on the Use of Sea-Water in the Diseases of the Glands. His dry tome does not exactly appeal to the imagination. The cures he suggests are sea baths, drinking seawater, possibly with a dash of milk, and an air cure.

Postcards from Ostend and Scheveningen, which in the nineteenth century were the most popular coastal towns in the Low Countries for immersing body and soul in search of medicinal salvation

Postcards from Ostend and Scheveningen, which in the nineteenth century were the most popular coastal towns in the Low Countries for immersing body and soul in search of medicinal salvation© Image Bank Kusterfgoed / Wikimedia Commons

The English craze soon floated over to Ostend. In 1783, William Hesketh, an innkeeper and hotelier in Ostend, set up the first bathing machine on the beach. It was a sort of carriage that could be rolled into the sea, after which the ladies could descend the steps to discreetly enter the waves. Despite this innovation, it was not until the mid-nineteenth century that medical bathing became established on the Belgian and Dutch coasts. Scheveningen and Ostend were especially popular destinations for immersing body and soul in search of medicinal salvation.

Heroic means

The sea bath treatment was so much more than just a fun splash. It consisted of a meticulously sophisticated combination of cold and warm sea baths, wave pools, immersion, irrigation, showers, and warm sea sand cures. Notorious “water doctors” such as Louis François Verhaeghe, Henri Noppe, and Petrus Marinus Mess advocated for the beneficial effect of seawater on the body and mind. They wrote scientific publications with sparkling titles such as Noppe’s The Benefits of Sea Baths to Cure Diseases and Weakness of the Sexual Organs in Women and Pubescent Girls as early as 1852. According to them, the sea could heal sorrows, strengthen morals, treat vague complaints that manifested as digestive problems, general weakness, anxiety attacks, irregular or heavy menstruation, nervous disorders, unexplained pain, mood swings, and/or headaches.

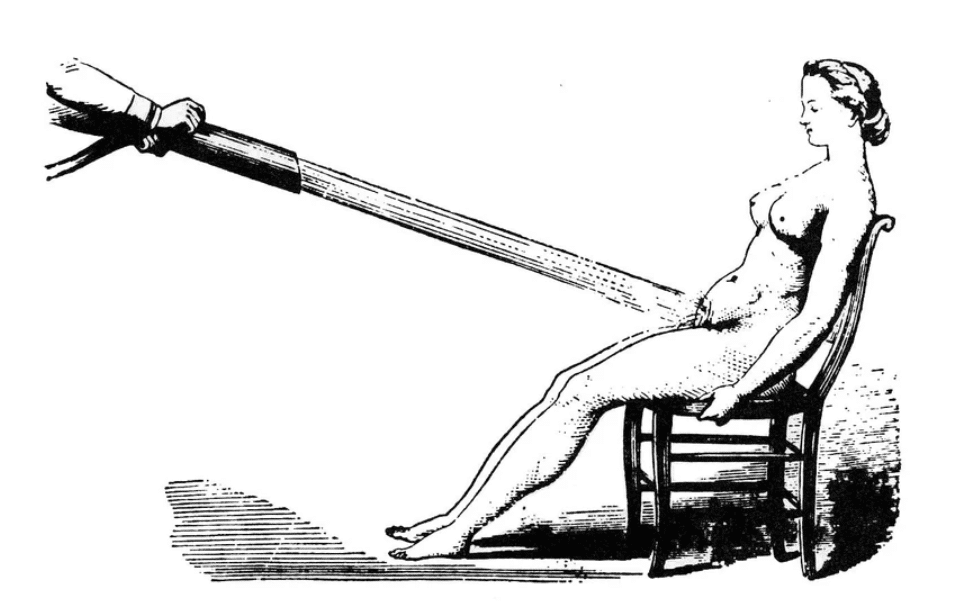

Etching of a 'wave machine' from the book Ha Doctor Ho Doctor. Crazy Medicine from Grandfather's Time (1976). In the mid-nineteenth century, sea bath cures became common on our coasts. Water doctors advocated the beneficial effect of seawater on the body and mind.

Etching of a 'wave machine' from the book Ha Doctor Ho Doctor. Crazy Medicine from Grandfather's Time (1976). In the mid-nineteenth century, sea bath cures became common on our coasts. Water doctors advocated the beneficial effect of seawater on the body and mind.In the Medical and Topographical Notice Concerning the Sea Baths at Ostend, sea doctor Georges Hartwig promised a “heroic remedy,” especially for women. Because sea bathing could arouse the appetite and activate secretions, it promoted blood circulation and, by counteracting the disastrous overload of the nervous system, increased muscle strength. Every year, a large number of Hartwig’s patients descended upon Ostend, where they hoped to find a new life and their long-lost happiness.

Preferably at high tide

Sea cures are largely women’s cures, for what was called female ‘hysteria’. Hysterical women were said to suffer from a disturbed mind and a derailed sexual drive. Hysterics were regularly advised to get married, ride horses, or be fingered by midwives. Based on similar reasoning, sea baths were said to promote blood circulation in the genitals and lower abdomen. According to Georges Hartwig, waves are highly suitable, preferably at high tide:

The shock of the waves greatly increases the effects of bathing in the sea: first by causing a stronger and faster reaction, then by giving the entire nervous system a violent shock. (…) In Ostend, the chorus of complaints is loudest when the wind stops pushing the tide towards the coast, and the waves no longer break on the shore.

Unlike the more exalted tuberculosis spas in the mountain sanatoriums, there was little romance surrounding hydrotherapy in the gray North Sea

In the absence of waves, the pelvic shower was used, in which jets of water were directed at the clitoris under great pressure. Women, the story goes, “often came out of the shower saying they felt as embarrassed as if they had drunk champagne.”

According to the nineteenth-century sea doctor Georges Hartwig, a 'pelvic shower' was ideal for promoting blood circulation in the genitals and lower abdomen.

According to the nineteenth-century sea doctor Georges Hartwig, a 'pelvic shower' was ideal for promoting blood circulation in the genitals and lower abdomen.Unlike the more exalted tuberculosis spas in the mountain sanatoriums, there was little romance surrounding hydrotherapy in the gray North Sea. While tuberculosis was a disease with a kind of artistic halo, the same could not be said about vague complaints or hysteria. That may explain why there are so few novels in which the medicinal sea cure in the Low Countries appears. Yet we know that famous writers sought relief for their tormented minds and battered bodies in the chilly North Sea waters. For example, Nikolaj Gogol, a masterful author and a notorious hypochondriac, visited Ostend several times for a bath treatment. Yet not a trace of this can be found in his literary work.

The healing power of… the seaside city

When Ostend, after years of procrastination and fuss, finally opened its Thermae Palace in 1930, the peak era of medicinal treatments in the North Sea had already ended. The growing belief was that therapeutic effects could be found not in the sea, but at the seaside. “A hypochondriac can be cured even by the simple fact of living in a place where he could daily contemplate the spectacle of the sea,” is how historian Thierry Terret summarised this trend.

Beach carriages in Scheveningen

Beach carriages in Scheveningen © Wikimedia Commons

The cultural and social activities of sea bathing became more important than the bath itself. Louis Couperus, for example, describes in Eline Vere (1889) how Scheveningen is a seaside resort where the spa is only a landmark in the crowd of bathers:

As if released from a trap of oppression, they quickly descended the steps of the terrace, crossed the road and hurried over the broad steps that led to the beach. The large basket chairs stood close together, as if they had been put away… And over the sea, on high, in front of the facade of the Spa, in a glow of gaslight, a hell of a commotion roared.

Label from the 1930s of Ostend Thermal, medicinal water from the Ostend thermal baths in Thermae Palace

Label from the 1930s of Ostend Thermal, medicinal water from the Ostend thermal baths in Thermae PalaceCoastal villages began emerging as places of fun and relaxation with beautiful villas and eclectic buildings, long promenades, pricey restaurants and equally expensive hotels, flashy theaters and race courses. Seaside resorts such as Scheveningen and Ostend were settings for civic display, of seeing and being seen. The socialites strolled on the promenade or in the parks, visited the racetrack and enjoyed concerts and theater in appropriate outfits and company. Rosalie Loveling describes Ostend in the novella Miss Leocadie Stevens (1876) as such a place:

When one stays in Ostend, it is as if all the distant and half-forgotten friends visited each other here again. One cannot walk down the dike without seeing people who meet each other here and, without worrying about the strangers who swarm around them, express their joy and amazement out loud.

The seaside resorts became places of idleness and entertainment. The fact that they happened to be located by the sea was simply an added bonus: “The pursuits of the sea waters are indeed becoming less numerous than the games of glances, the fashion exhibitions and the meetings,” wrote Terret. The conviction was slowly growing that doing nothing, lounging and endlessly staring at the horizon were useful benefits of a stay by the sea. In the words of Rosalie Loveling:

How freshly the sea wind blew in the sight of young Leocadie! She sometimes reproached herself for her laziness, but enjoyed it nevertheless; for here, idleness was neither boredom nor despondency but a feeling of voluptuousness and quiet contentment that swept over you.

Salty comfort and self-care

And yet, and yet… That bourgeois appearance in one of the glamorous seaside resorts did not always heal the tormented woman’s soul. Drowned coastal cities were also a refuge for women with lost loves, surrendered ambitions, forgotten desires, and mental decline. We read this in novels such as Eline Vere by Louis Couperus or From the Cool Lakes of Death (1900) by Frederik van Eeden.

But also in more recent literature, such as The Beach of Ostend (1993) by Jacqueline Harpman or Pier and Ocean (2012) by Oek de Jong, young women find their way in life on the beach and the dike. Bestsellers such as Winteren (Wintering) by Katherina May or The Salt Path (2018) by Raynor Winn feature contemporary women who mentally refresh themselves and physically bathe in the sea, as a form of salty self-care.

That bourgeois appearance in one of the glamorous seaside resorts did not always heal the tormented woman's soul

We may laugh about the medicinal effect of waves on hysterical ailments. And, though the healing power of the sea for more contemporary women’s issues is also not (yet) scientifically watertight, there are some compelling findings. Winter swimming is said to produce dopamine and serotonin in the brain and thus boost feelings of happiness. Beneficial sea substances, such as iodine and iron-rich substances, are said to be superpowers that penetrate the skin and thus pass on their beneficial power to the body.

The healing power of the sea seems tailor-made for women; both for those under the care of nineteenth-century water doctors and for modern women

The healing power of the sea seems tailor-made for women; both for those under the care of nineteenth-century water doctors and for modern women© Nina Descheres / Unsplash

Salt on your skin makes you happy; that much is clear. Moreover, the healing power of the sea seems tailor-made for the female of the species, both for nineteenth-century water doctors and for modern women. After all, women have often found what they need in or by the sea: health, peace, balance, tranquility or simply happiness.

However functional the sea is in that healing reasoning, there is even more to be found in the imagination evoked by the sea and the women’s own natures. What if the sea does not tame, cool or temper the feminine impetuosity, but rather cherishes and celebrates it?

The sea, a lover

The celebration of female impetuosity is a recurring theme in Caro Van Thuyne’s oeuvre. In Bloedzang (Bloodsong) (2023), for example, the sea is body and love. The bathing experience is wild, intense and raw:

And my breath swells with it, how higher, higher, higher the wave goes, the deeper my breath swells and swells and swells, deep into my stomach, it stretches the walls like the wave stretches in its high-high-stretched skin. And when the wave breaks unbearably, the smooth sea-blue creature that is my breath makes a graceful somersault at the bottom of my stomach and pushes itself off from the bottom with its limbs stretched, making its way upwards, to slowly spill out and drain me.

In The Time Denier (2022), Ilse Ceulemans describes bathing in the sea as a passionate caress from a lost loved one, even though the main character only finds his dead goldfish Jeanny, which he, himself, dumped in the sea: “Then I run to the sea. Ten thousand Jeannies greet me as I enter the water. My chest almost splits with pleasure.”

The sea is also a lover in A Drink with Barry (2005) by Christophe Vekeman. Barry is a would-be writer who feels “like a wine bottle cork thrown into the sea and condemned to float directionlessly on the waves.” His mistress Martha, on the other hand, feels like a fish in water in the sea. This makes him feel insulted and humiliated, pushed aside. He is jealous of that “gray, stinking pool of water” that can satisfy his woman–something he himself is unable to do.

The imagination of the sea can explain why wild women like Caro in Bloedzang, Martha in A Drink with Barry, Eline in Eline Vere or Dina in Pier and Ocean, and all those passionate winter swimmers seek refuge at the seaside and in the sea. The sea is healing for them, not as the gentle caress promised by medical sea cures or salty self-care, but as a test of strength against an indomitable natural element, with wild waves and intense currents, unfathomable depths and deceptive torments, with ebb and flow, spring – and neap tide.

Tülin Erkan makes the play between woman and sea tangible in a bather’s portrait that she wrote in Ostend:

See how they play, the woman and the sea. The rolling and bulging and gurgling and bubbling and struggling and swirling and raging and frothing and fizzing and seething and fuming and cursing. Feel how everything is suddenly windless, the sowing channels filled with water.

The sea is a lover, and bathing in the sea is a game of love.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.