In her fourth and final column concerning polarisation in society and distrust of the established order, Hind Fraihi reflects on the fight against racism as carried out by the Black Lives Matter movement. ‘It is remarkable how a battle against superiority is conducted with a certain sense of superiority,’ she writes. ‘In the past, I have been “too brown” for some people. More recently, I am supposedly “too white”. It was not until this strange year of 2020 that I have felt like an antipode of another, stuck in the middle between the polarizing extreme right and blacktivism.’ The stride doesn’t have to be this way: anti-racism activists in the 1990s were unified, diverse and colour blind.

The first shot was fired about six months ago from the Dam in Amsterdam. Shortly thereafter, other cities followed: Utrecht, Enschede, Nijmegen, Rotterdam and more. It was the first week of June 2020, when thousands of people took to the streets in protest against racism and police violence. The worldwide protest spread like wildfire.

Black Lives Matter protest in Amsterdam, 1 June 2020

Black Lives Matter protest in Amsterdam, 1 June 2020© Shane Aldendorff / Pexels

On 7 June, Brussels entered the fray as ten thousand protesters demonstrated their support for Black Lives Matter. The protests sparked at what has been called a turning point. The catalyst: the police shooting of an African-American named George Floyd.

When speaking about the fight again racism, I do not care for terms such as momentum, turning point or revolution. And that is simply because the struggle for emancipation or equality rarely makes a quantum leap. Branding these moments as “revolutionary” nullifies the lengthy work that is so characteristic of a struggle. Fire simply cannot flare without sufficient fuel – which may not be visible but is must be abundantly available.

Anti-racism must not become some kind of by-word for a flirtation with activism

So, if anyone should ask for my “take-away” from this year; well, it’s not George Floyd and it isn’t the fight again racism. I’ve been waging that war my entire life so it’s not something I would put on a year-in-review list. Anti-racism must not become some kind of by-word for a flirtation with activism. That would relegate the struggle to a one-dimensional form of activist self-gratification ideally suited to social media. And, at a certain point, it literally became one-dimensional. A black surface, a square, went viral on social media about a half-year ago on Blackout Tuesday. In support of the George Floyd protests, celebrities, influencers, brands and corporation posted completely black messages on Instagram. In fact, their virtual “support” was an act of grandstanding designed to illustrate their personal virtue.

It is remarkable how a battle against superiority is conducted with a certain sense of superiority. ‘There were a lot of influencers who participated in Blackout Tuesday and now do not even remember doing so,’ says writer Dalilla Hermans in the women’s magazine Feeling, in an article looking back on the wave of protests. What should have been serious and effective activism was hijacked by selfie brigades the world over.

‘Is this a summer hype or are we at a turning point of history?’ asked Dutch radio NPO Radio 1 in a teaser. The question is provocative clickbait, as it should be, but also almost a quip. The answer, of course, is that BLM is neither.

Femke Halsema, the Mayor of Amsterdam

Femke Halsema, the Mayor of Amsterdam© Wikipedia

And from the political arena, Femke Halsema, the mayor of Amsterdam, had these epic words to share: ‘What started with a few activists who dared to question injustice and start confrontational conversations, who were ignored and ridiculed, or more often hated and threatened, has over this past month grown into an unstoppable new popular movement of mothers and daughters, fathers and sons, grandparents and grandchildren, shopkeepers, teachers, nurses and police officers.’

This kind of grandiose speechmaking not only betrays a misunderstanding of the decades-long fight against racism, but also serves to create an epoch-moment large enough to minimize everything that came before and will come after. It is a patronizing vision shrouded in covetousness and grotesque rhetoric that can lead to only one result: the collapse of the fight against racism. Or, as has often been said before, the fight is doomed to fail at the hands of a “new generation”.

But ‘presenting a generation of activists as “new” only isolates them from the activists who came before, and especially from what they – we – could learn from their successes and failures,’ said Olivia Rutazibwa, teacher and author of the de-colonial manifesto Het einde van de witte wereld (The End of the White World).

What came before was a long fight in all its forms: petitions, school sit-ins, policy recommendations and intense political pressure used in the realization of the immigrant right to vote, with my brother Tarik as one of the pioneers. But, yes, certainly also a battle in the street. Just think of the anti-racism movement of the early 1990s. I remember it as if it were yesterday. On 24 October 1992, there was, amongst others, the Hand in Hand in Brussels march, drawing 40.000 protesters. I was sixteen, plunged into a sea of people from every corner of the country. That number was equalled two years later on 27 March 1994. And in 2006 there was a White March in Antwerp, following the racist murders committed by Hans Van Themsche, that drew 15,000 to 20,000 demonstrators.

The demonstrations of the 1990s were all about unity. The ranks were formed regardless of colour, origin or history

The turnout was huge in contrast to June 2020 (there was, of course, no pandemic in 2006), and the indignation, the misunderstanding and the even the rage were no less present. In the early 1990s, the shock and dismay about the extreme right-wing advance in the elections were considerable. Vlaams Blok (Flemish Block) had its first breakthrough in the 1988 municipal elections in Antwerp. On Black Sunday, 24 November 1991, another breakthrough occurred when they got 10 percent of the votes throughout all of Flanders for the first time. The voters had sent a signal. And young people sent a signal back supported, amongst others by Youth against Racism in Europe.

Why am I referring to that? Because it is not about who comes first, but about who creates unity. The demonstrations of the 1990s were all about unity. The ranks were formed regardless of colour, origin or history. There were no boxes to tick or any fuss about identity. Terms such as woke were not part of the movement’s vocabulary, and there was no talk about white privilege.

These days, rabid BLM supporters view colour blindness as a form of micro-aggression designed to erase ethnic identity and experience. The differences, it seems, must now be emphasised. Even inter-African differences. For example, is a victim of police brutality “black enough” to be the subject of a BLM protest?

In the run-up to the Brussels BLM demonstration, there was some discussion whether the parents of Adil and a brother of Mehdi, two young men who died during police intervention in Belgium, should even be included in the protest.

These days, rabid BLM supporters view colour blindness as a form of micro-aggression designed to erase ethnic identity and experience

‘Some thought the demonstration should focus on “Black Lives Matter,” not “North-African Lives Matter”. Racism against black Africans is not the same as racism against other people of colour. But for the next of kin, the focus was primarily on police brutality and young people with North African roots are also confronted with this. That was not an issue for me. In my opinion, they are African as well. They deserved a place at the event, and they got it,’ said youth worker Muamba Bakafua, of the Brussels non-profit organization Change in De Standaard.

Let’s take a closer look at those two sentences: The demonstration should focus on “Black Lives Matter,” not “North-African Lives Matter.” And,

Racism against black Africans is not the same as racism against other people of colour.

There appears to be some system of hierarchy in the fight against racism.

So, if someone should ask me what my take-away is from the year 2020, I would have to say it was undoubtedly my colour. In years past, I was too brown for some people. They felt I should “go back where I came from.” But more recently, I have been too white. More than ever, I am in-between worlds. The Afropean in me – a European with African roots – can experience the cultures of two continents to my heart’s content. But that is one too many for some people, including Africans. Then I am all of a sudden too Belgian.

Apparently, a person who is (essentially) white with brown pigment experiences racism differently and should therefore fight differently than black pigmented people do. And that is a fight in which, according to diehard blacktivists, whites have no place at all. They must be silenced lest that colonial blood flows into all the crevices.

That vision, with which I have already been confronted, manifests itself as a kind of Mendeleev’s Table for adepts in the fight against racism. Against that, my North African roots can only be lightweights on the apothecary’s scales. According to some BLM supporters, I lack an important element: a transgenerational pain that goes back to colonialization or slavery. Or, in other words, my roots are not in Congo.

If someone should ask me what my take-away is from the year 2020, I would have to say it was undoubtedly my colour

I have never considered myself as such an antipode of others as I have in this exceptionally weird year where I have stood between a rock and a hard place, on a playing field of polarising extreme right politics and blacktivism. Never before have I looked back like this to those Sundays in Brussels when I protested with the masses as an adolescent. So diverse and so colour blind. Always looking forward.

The racism struggle of the 1990s was not only characterized by unity without any imposed English-language vocabulary, it was also first and foremost a battle that looked forward in a unifying way and moved forwards in courage, with the past only recognised as baggage, not as a condition of equality.

Do North Africans have nothing distressing in their past? Hasn’t brown blood also flowed throughout “white” history? European war commemorations usually pay slight attention to the spilt blood brought in from the colonies. Yet there are plenty of examples.

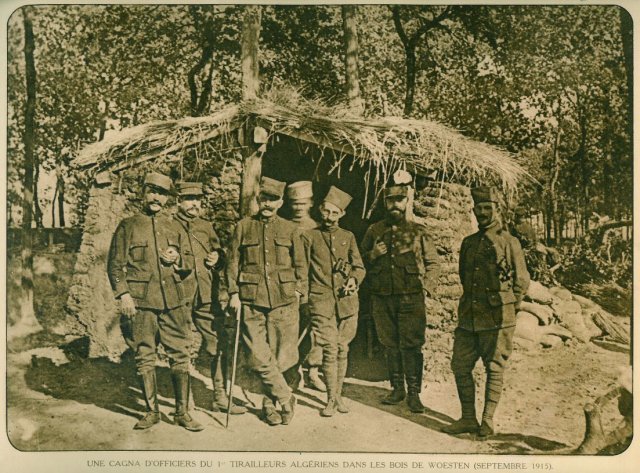

Algerian officers during the First World War near Poperinge in the Belgian Westhoek region.

Algerian officers during the First World War near Poperinge in the Belgian Westhoek region.© Westhoek Verbeeldt

On 22 April 1915, the Germans used poison gas for the first time in the battle at Steenstrate. The hardest-hit soldiers were the indigènes,

indigenous soldiers of the 45th Algerian Division. And in the Second World War? Consider only the most famous: the Battle of Gembloux. On 15 May 1940, along the Ottignies-Gembloux railway line, there were mainly Moroccan soldiers on the front line. Many of them, despite the military success of this skirmish, never saw the African sun again. They shed their blood for liberation.

Should I carry their suffering in me? I’d rather carry their courage. And consider this point: Europe was not traversed by ethnic dividing lines in war. Let that also be the case in times of peace, and certainly in the fight against racism. Unity creates the future.