Women’s Suffrage: An Ongoing Struggle

Exhibitions, lectures, guided walks and a website launched by the House of Representatives (Tweede Kamer): clearly, the Netherlands is sparing neither time nor efforts to celebrate the centenary of universal suffrage. However, this anniversary should actually force us to stop and think. After all, it symbolises women’s long, arduous struggle to claim equal status in society. Belgian women, incidentally, had to wait until 1948 before they were granted the right to vote. A year later, on 26 June 1949, the first parliamentary elections followed in which women were allowed to vote.

Women’s suffrage as well as the democratisation of education were major issues in the so-called ‘first wave of feminism’ in both the Netherlands and Flanders. It started roughly mid-19th century and lost some of its momentum during the interwar period.

Life for women in the 19th century was no walk in the park. The bourgeois ideal’s growing popularity meant that men increasingly dominated the public sphere, while women were expected to stay at home. Against a background of advancing industrialisation, women workers had become a sign of poverty. Beliefs linked to that view were also reflected on a political level. Democracy only included affluent male citizens. Women, similar to low-income men, were not allowed to cast their votes.

The Association for Women's Suffrage, circa 1917

The Association for Women's Suffrage, circa 1917© International Institute for Social History, Amsterdam

Women to the barricades

It should not come as a surprise that this eventually caused an outcry. Initially in the Netherlands, and in Belgium not long after, women were getting organised. In doing so, they followed in the footsteps of international woman suffrage movements in the UK and US. Demonstrations, protest movements and lectures were being planned, and numerous articles denouncing the position of women were published.

In the Netherlands, Aletta Jacobs (1854-1929) was one of the main protagonists in the story of women’s suffrage. In 1883, she sparked the debate when she wanted her name to be added to the voter registration list. After all, she argued, the constitution only mentioned ‘Dutch citizens’ when it came to enfranchisement. Despite the fact that women were not explicitly excluded from voting, her request was refused.

In 1894, she founded the Vereeniging voor Vrouwenkiesrecht (VVK; Association for Women’s Suffrage) with Wilhelmina Drucker (whose name would later be appropriated by the Dolle Mina’s, or Crazy Minas). In 1917, partly owing to their fight, passive suffrage allowed women to stand in elections for the House of Representatives.

The board of directors of the Association for Women’s Suffrage in Apeldoorn, including Wilhelmina Drucker and Aletta Jacobs, in 1913

The board of directors of the Association for Women’s Suffrage in Apeldoorn, including Wilhelmina Drucker and Aletta Jacobs, in 1913© Spaarnestad Photo

Belgium lags behind

In Belgium, things did not move quite as quickly. To start with, women’s rights advocates such as Marie Popelin and Isala Van Diest mainly focused on education and economic as well as legal equality. The Nationale Federatie van Socialistische Vrouwen (National Federation of Socialist Women), with Isabelle Gatti de Gamond as its first secretary, was initially the main advocate for women’s right to vote in Belgium. At the same time, socialists in particular were suspicious of women’s suffrage. In fact, they shared concerns with the liberals about women potentially voting for the catholic parties in their droves, as they believed women would be strongly influenced by the priest.

Marie Popelin (1846-1923)

Marie Popelin (1846-1923)Even though at the start of the 1920s a few rather modest victories were recorded, including passive suffrage at a provincial and national level, and the right to vote in municipal elections, this reasoning – in part – would continue to burden Belgian women until after the end of World War II. It was not until 1948 that voting rights for Belgian women were decreed by law. Belgium is therefore one of the very last European countries to introduce women’s suffrage – Only Greece would allow it even later.

Still a long way to go

As it happens, Switzerland would not follow suit until quite a few years later. It was not until 1971 that Swiss women were granted the right to vote. In South Africa, women of colour were not allowed to vote until the end of Apartheid in 1994, and in Saudi Arabia women were only granted the right to vote in 2015. Moreover, the instalment of suffrage in the Netherlands in 1919 did not include women in Dutch India, Surinam and the Netherlands Antilles. Both Surinam and the Netherlands Antilles had to wait until 1963 and 1948, respectively.

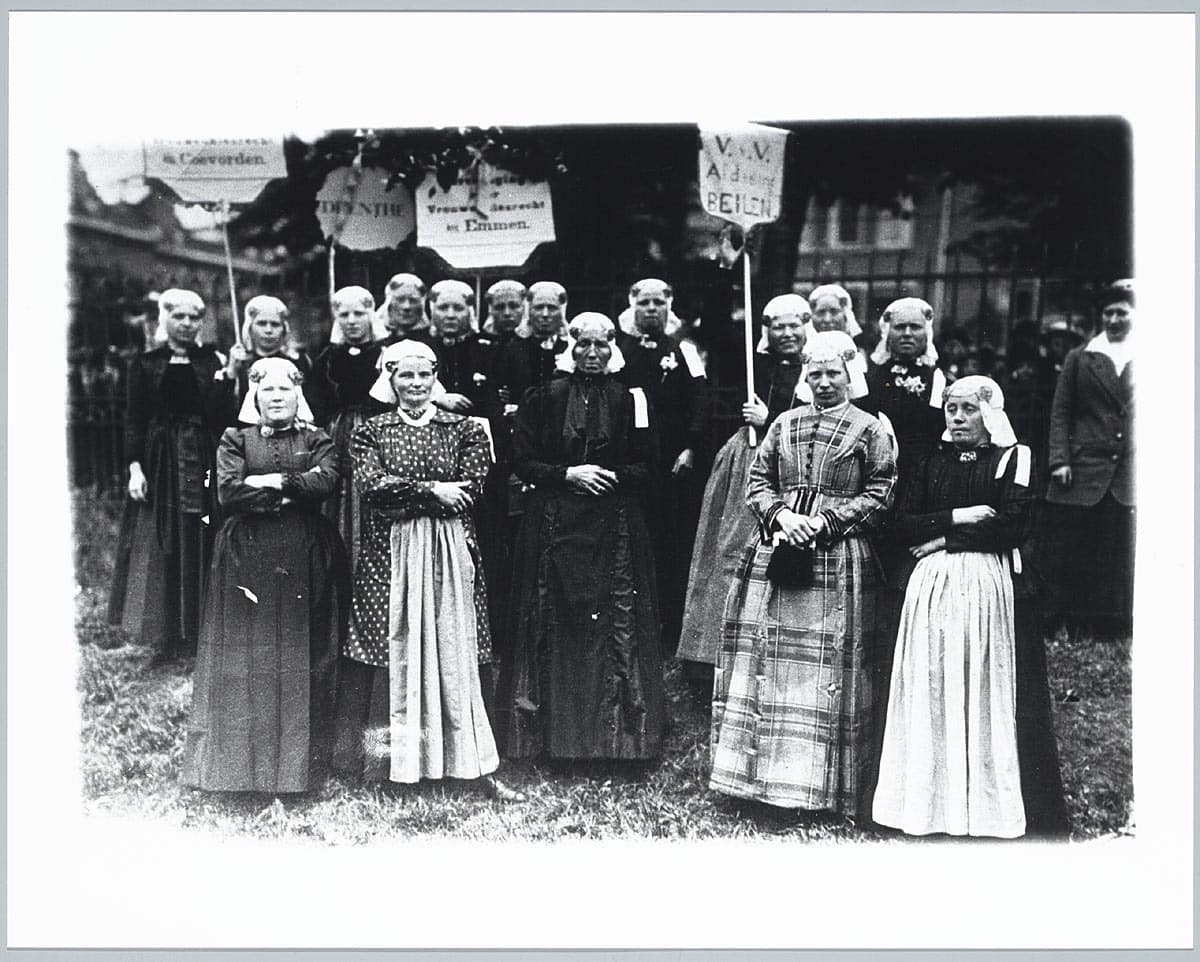

Members of the Association for Women’s Suffrage in Drenthe in 1916

Members of the Association for Women’s Suffrage in Drenthe in 1916The widespread fear that all women would vote catholic proved to be unnecessary. Women and men cast their votes in an equally diverse way. However, it is true that women’s suffrage did not automatically impact female participation in politics. In fact, In Belgium, a female minister was not appointed until 1965, whereas in the Netherlands that first happened in 1956. Even today, gender equality in both countries remains a distant dream.

A women casts her vote in Amsterdam in 1920

A women casts her vote in Amsterdam in 1920One hundred years after the brave fighters of the first feminist wave finally booked some results, we must conclude that we are not quite there yet. In Western countries too, women continue to be the first and most hardly hit victims of the economic downturn, violence against women remains a problem, women of colour especially are suffering, and we all have to battle against gender norms that are all too strict across various layers of society.

The Dutch celebrations commemorating the anniversary of women’s suffrage are actually the prefect incentive to reflect on this, and for us to jointly decide how we can finally rid the world of these problems.