Augustin Goovaerts, a Belgian Palace Builder in Colombia

Churches, schools, hospitals, even slaughterhouses and prisons – Augustin Goovaerts has designed them time and again. Despite this, the Brussels-born architect is hardly known in Belgium. Augustin Goovaerts predominantly acquired his fame in Colombia in-between the world wars. Historian Peter Daerden flew to South America to rediscover this palace builder.

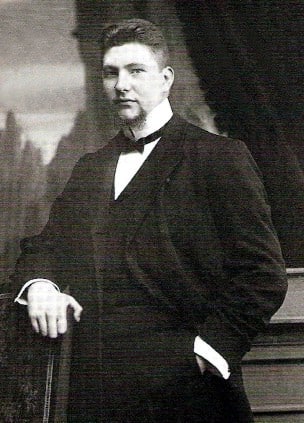

Augustin Goovaerts was born in 1885 into an art-loving family – his father Alphonse a composer and musicologist. After his studies in architecture and engineering, he began working with well-known colleagues including Edmond Serneels and Victor Horta. A portrait photo of Goovaerts from that time shows a somewhat dandy-like, well-built man with a bow tie and a frivolous goatee. Above a dizzyingly high celluloid board, he looks to the future with confidence, life seems to be treating him well.

Architect Augustin Goovaerts (1885-1939)

Architect Augustin Goovaerts (1885-1939)© Wikipedia

However, in 1914 this Belle Époque came to an end. At the beginning of the First World War Goovaerts put himself forward as a volunteer for the Belgian army. During a battle in Duffel, in the province of Antwerp, he was injured and repatriated to a military hospital in Calais. Instead of returning to the front, he remained in France to teach Belgian soldiers.

In 1916 Goovaerts married Marie Desmet in Liverpool and the couple soon had two children. Until 1919 the family lived in Vernon, a small city in the Seine Valley. After the war, there was little opportunity for architects in Belgium, and Goovaerts had a wife and children to support. Through a twist of fate, he came into contact with Henry Jalhay, the Colombian consulate for Belgium. It turned out that Jalhay’s predecessor, the Colombian Pedro Nel Ospina, was eager to find an architect to renew his city of Medellín and to build public buildings there. Ospina wasn’t just anyone, but an influential politician who was even elected President of Colombia a few years later. His years of service in Belgium – where his children had also attended school – had left him with an excellent impression of the country.

Goovaerts was seen as a well-behaved, law-abiding Catholic

‘To understand the choice to appoint Goovaerts, you need to understand the country itself’, explains historian Luis Fernando Molina Londoño in the capital city Bogotá. ‘Colombia is an overwhelmingly conservative country, and the Department of Antioquia – where Goovaerts was due to work – was the most conservative of all. That was the case 100 years ago, and it still is today.’ He looks at me with a smile, which I could describe as affable – he himself comes from that region. ‘Goovaerts was seen as a well-behaved, law-abiding Catholic. Not someone who would go all out. Modernización sin modernidad (modernisation without modernity) was the slogan of the time. This Belgian man fitted perfectly into that picture.’

Goovaerts seized the chance with both hands and travelled to Medellín with his wife and children, arriving on 20 March 1920. There he worked incredibly hard and under very difficult circumstances – I try and imagine the Belgian giant, sweating away in his studio without any running water, the ceilings eaten away by the termites, his plump body assaulted by fleas and midges.

The Gaudí of Medellín

View of Plaza Botero and Museo de Antioquia from the fourth floor of the Palacio de la Cultura Rafael Uribe Uribe

View of Plaza Botero and Museo de Antioquia from the fourth floor of the Palacio de la Cultura Rafael Uribe Uribe© Medellín Guru

My reconnaissance of Medellín starts in the city centre. From the upper floors of the Palacio de la Cultura Rafael Uribe Uribe I have a beautiful view of the Plaza de las Esculturas. In the adjacent Museo de Antioquia, on the same public square, I visit the extensive collection of Botero paintings: an ironic reflection of the Colombian bourgeoisie. Leaving the museum, I pass the old Cathedral of Veracruz and continue walking until I see, a little further ahead, metallic, onion-shaped towers glimmering in the sun. The former government building Palacio Nacional is now occupied by sports- and casual wear businesses. As in much of South America, the sellers are far from shy; cries of ¡a la orden! fill the air. With its arcades and many floors, this building has an unexpected lugubrious quality. Later, I read that the top floor is a particularly beloved place from which to jump to one’s death.

The Palacio Nacional is a former government building turned into a commercial centre.

The Palacio Nacional is a former government building turned into a commercial centre.© Flickr / Felipe Restrepo Acosta

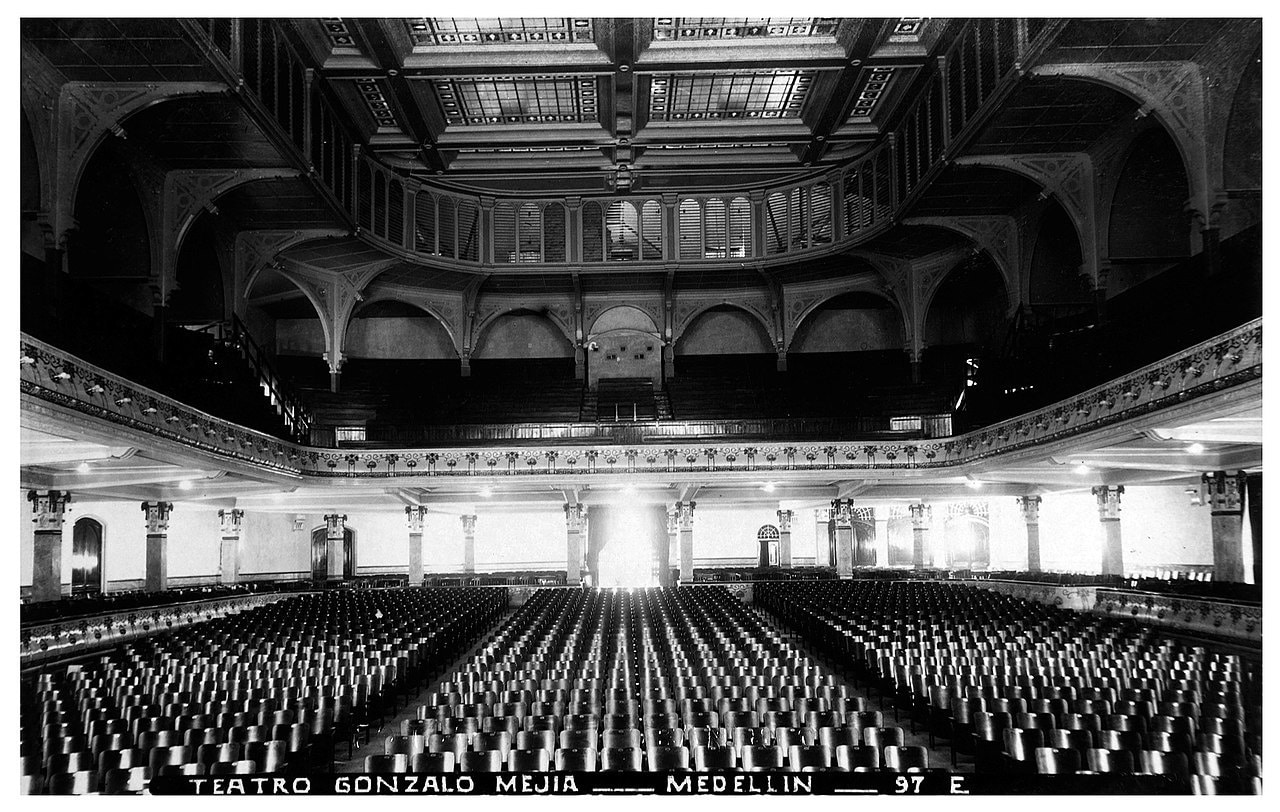

Here I am absolutely immersed in the Goovaerts universe; this is one of his best-known creations. Goovaerts was, all things considered, as important to Medellín as Gaudí was to Barcelona. Unfortunately, however, I would not be able to see his first prestige project, a luxurious art nouveau complex in the city centre. The Gonzalo Mejía building housed a hotel and a theatre, and the latter – the Teatro Junín, with no fewer than four thousand seats – was the seventh-largest theatre in the world. At the October 1924 inauguration, an orchestra led by Goovaerts himself played the Colombian national hymn, and a Charlie Chaplin film was shown. Despite the forty-two meters between the audience and the screen, it appears that the image was pin-sharp.

The Gonzalo Mejía building, original black and white photo, by an unknown author, illuminated by Juan C. Posada S.

The Gonzalo Mejía building, original black and white photo, by an unknown author, illuminated by Juan C. Posada S.In 1968, the entire building was demolished to make way for the Coltejer tower, a modernist colossus that juts up 175 meters into the air. It is particularly cynical that Belgian architects from Goovaerts’ age didn’t only face the destruction of their work at home – consider how many buildings by Horta and his contemporaries were torn down – but that their creations didn’t escape this fate thousands of kilometres away either.

Teatro Junín in 1924

Teatro Junín in 1924© Wikipedia

Elsewhere in the region Goovaerts also made his mark – in municipalities with powerfully poetic names like Anorí, Yarumal, El Limón, Titiribí, Copacabana of Fontidueño, places he visited astride donkeys when necessary, because neither road nor rail connections yet existed. Those with time and money to spare could invest in a new tourist trail, a sort of Ruta Goovaerts, that encompasses all of the locations where the Belgian’s architectural fingerprints are still to be found. And yet, when I decided to visit just one location, it became immediately obvious to me what a Sisyphean task this would present.

Hotel designed by Goovaerts in El Limón

Hotel designed by Goovaerts in El Limón© Peter Daerden

El Limón is still a bafflingly isolated destination. Unserved by bus, it is only reachable aboard a motorised goods wagon that creeps, at a snail’s pace, through an almost century-old railway tunnel. Upon leaving the tunnel, the surroundings could be mistaken for a filmset. The charming station makes a forlorn impression, the warehouses of yesteryear are long gone, and it has been forever since a train was last spotted here. The hotel that Goovaerts had built in 1921 – intended for the workers that built the connecting tunnel – is thankfully still standing, its scarlet-red doors, balconies and balustrades kissed by the sun and marvellously contrasting with the surrounding vegetation. Perhaps it is the unexpectedness of this encounter, popping up like a mirage out of a no man’s land that leaves me feeling strangely moved.

An American Bruges

As long as he worked for private individuals, Augustin Goovaerts had it relatively easy. More obstacles could be foreseen for the large government projects, which were slower to start and more academic in style. The government palace Palacio de Calibío was to become Goovaerts’ biggest test yet: for this project he had designed a five-storey building with 315 offices, a large parliament room, and a residence for the governor. Later the palace became a centre for administration and was renamed to Palacio de la Cultura Rafael Uribe Uribe. Walking through the narrow corridors, under neo-Gothic arches and art deco lighting, between sturdy white columns with floral patterns, and past high wooden doors inlaid with sober stained glass, one experiences a very specific atmosphere that immediately creates an image of the time period. Where else on this tropical latitude, I wonder, are the echoes of the European interwar period so strong?

Palacio de la Cultura Rafael Uribe Uribe, previous the government palace Palacio de Calibío

Palacio de la Cultura Rafael Uribe Uribe, previous the government palace Palacio de Calibío© Medellín Guru

Today the palace is the pride of Medellín and a natural draw for tourists. But contemporaries of Goovaerts relentlessly ridiculed the project, considering it a malignant growth on Colombian soil. An increasingly intense polemic grew, especially in the liberal press. Goovaerts was accused of holding outdated views and being out of touch with the local culture and context. In order to distinguish themselves from the outdated capital Bogotá, people wanted functional government buildings to be built in Medellín, buildings adapted to the new modern times, where rationality ruled. But what did people get? Neo-Gothic! Walls from the Middle Ages! Church-like spires! His critics taunted the man, with a sometimes barely concealed tone of nationalism and anti-church sentiment. The newspaper El Heraldo de Antioquia denounced the ‘extremely narrow foreign view’ of the Belgian schemer. One Member of Parliament expressed fear that Goovaerts was transforming the city into an ‘American Bruges’. Colombia’s most influential poet, León de Greiff, scornfully called the new government building ‘Goovaerts’ Abbey.’ It was said that passers-by often made the sign of the cross as they passed the site, convinced that a church was under construction. The leading painter Pedro Nel Gómez described the construction as ‘prudish’.

Dome of the Palacio de la Cultura Rafael Uribe Uribe

Dome of the Palacio de la Cultura Rafael Uribe Uribe© Flickr

Goovaerts was also ridiculed by caricaturists, an excellent victim considering he weighed 90 kg and was of colossal physique compared to local standards. His professional dignity was severely compromised, but he picked himself up, dusted himself off, and continued to work imperturbably.

By 1928, Goovaerts’ imprint on Antioquia had become indelible. 74 schools and colleges, 6 slaughterhouses, 12 prisons, seven hospitals and 17 monuments and parks now bore his name as engineer and architect. He had also been involved in the design and construction of some thirty religious buildings. At this point he also had two large-scale projects under construction: the Palacio Nacional and the monumental Palacio de Calibío (today the Palacio de la Cultura Rafael Uribe Uribe). Goovaerts also taught and mentored young architects in Colombia, even paying for one of them to study architecture in Brussels.

However, the storm of criticism never really died down, and it is possible that this eventually wore Goovaerts down. On 30 July 1928, he wrote a parting letter ‘with a heart full of affection for Columbia’, before returning to Belgium.

Back in Belgium, Goovaerts worked on a few less spectacular projects. On 15 August 1939, he died of paratyphoid and leukaemia.

The Second Miracle

Historian Luis Fernando Molina Londoño took on the task of saving architect Goovaerts from oblivion.

Historian Luis Fernando Molina Londoño took on the task of saving architect Goovaerts from oblivion.© Peter Daerden

Goovaerts has remained an internationally unknown architect. His most important works -which have in many cases been adapted, were unfinished, or simply knocked down – found themselves in a region that was never in the spotlight, and attracted little or no foreign visitors. In Colombia too, interest in Goovaerts did not pick up again until the late 1980s. Only when his last major works were also threatened with demolition, did a counter-reaction grow. This brought about the restoration of the Palacio de Calibío in 1988. The once peaceful city of Medellín, meanwhile, had fallen prey to a merciless spiral of violence from gang wars, kidnappings and bombings. Amidst all the misery, a young historian, Luis Fernando Molina Londoño, took on the task of saving the architect from oblivion. He managed to track down Goovaerts’ descendants in Belgium. When he first arrived in Belgium in 1992, he was received almost theatrically: the Colombian flag had been rolled out and the national anthem was sounded from loud speakers. The event was still crystal clear to him. ‘I was completely surprised, the tears streamed down my cheeks.’

The Church of San Ignacio of Medellín was renovated by Goovaerts

The Church of San Ignacio of Medellín was renovated by Goovaerts© Wikipedia

In a letter written in 1991, before his first visit to Belgium, the Goovaerts family expressed their surprise at how young the Colombian researcher was. Molina explained to them the circumstances in which he was living and working: ‘With regard to my photo and your noting how young I look – the death rate in young people is very high in Medellín. I think I can even be considered pretty elderly at 30. In Colombia it is normal to see graffiti on the walls, which reads “Jesus lives… through a miracle”.’

So many years later, Medellín has once again become relatively serene. The world has rediscovered this city, it can be surprisingly pleasant to stay here, and the friendly Paisa’s will welcome you with open arms. Goovaerts’ name is also starting to reappear in travel guides and information brochures. In fact, those who visit the former Palacio de Calibío are now presented with a permanent exhibition all about this giant Belgian man. To not know who Goovaerts is, is no longer an option. Maybe that’s the second miracle.

- Consulted Sources:

Sint-Lukas Archives Brussels

Le Journal de la Famille Goovaerts.

Molina Londoño, Luis Fernando, Agustín Goovaerts y la arquitectura colombiana en los años veintes. Bogotá, 1998.