What We Could Do With Controversial Statues

To keep, to remove, or to tuck away in a museum? In his book on statues in the public space, ex-curator Ton Quik does not shy away from difficult questions. But he remains nuanced: statues deemed dubious can remain standing, but preferably after a transformation by artistic intervention.

In 1876, a statue of Jan Pieterszoon Coen was erected in Batavia. This can safely be regarded as a provocation of the first order – almost two and a half centuries earlier, in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), he had massacred nearly all fifteen thousand inhabitants of the Moluccan nutmeg island Banda and sentenced the rest to slave labour.

The statue in Batavia of Jan Pieterszoon Coen, the man who massacred 15,000 people from the nutmeg island Banda.

The statue in Batavia of Jan Pieterszoon Coen, the man who massacred 15,000 people from the nutmeg island Banda.© KITLV

In 1893, another statue was erected in his birthplace of Hoorn. He was posthumously venerated by the Catholic priest-politician Schaepman, who believed that with this sculpture, the artist had succeeded in ‘[awakening] our consciences’ – not, as you might expect from a man of the church, regarding Coen’s genocidal crimes, but regarding his forceful militant example: ‘Something great can be achieved in those Indies.’

At the time, the patriarch of the Dutch socialists Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis registered his dissent, denouncing Coen as ‘a bloodhound’ and declaring that he would rather see a statue of Multatuli, who ‘stood up for the rights of the downtrodden Javanese’ and who had died six years earlier. But Domela Nieuwenhuis was a lone voice in the desert. As late as 2006, a descendant of Schaepman, the Catholic Prime Minister Balkenende, still invoked the blazing optimism of the ‘VOC mentality’ as a worthy example for his wretched compatriots.

The more recently heightened sensitivity towards these dubious statues has undoubtedly stemmed from the Black Lives Matter movement

Such historical naivety has now become unthinkable. Balkenende’s political career might even be defined forever by that one statement about the VOC mentality. The statue of Coen in Hoorn, many people now think, has to go. Either done away with or placed in a museum, where it can no longer cause offence. And if it is allowed to stand, then let it at least be accompanied by a plaque that exposes the deeds and misdeeds of the unscrupulous gentleman. But there remains no definitive solution for the controversial statue. As long as public debates on the broader themes of discrimination, racism and exclusion continue, the municipality will continue to defer any decision on the matter.

The lingering controversy about Coen’s statue was the impetus for Ton Quik, the former curator of the Maastricht Bonnefantenmuseum, to publish a broad review of statues in the public space with his book Meer dan een beeld (More than a Statue). With great nuance, Quik delves into various points of view before unfolding his own perspective in a more general sense. ‘It is not the statue that is the problem,’ he says, ‘but the plinth, […] the act of commemoration.’ He declares himself in favour of ‘a form of activist heritage management that acknowledges the nature and function of the tribute but with respect for the work of art itself.’ To this end, ‘the pedestal and the artwork’ must be separated. And so purely on aesthetic grounds the work of art may remain, the problem lies in the politicization of the statue and in the painful emotions and memories it sometimes evokes.

Communards pose with the statue of Napoléon I from the toppled Vendôme column, Paris 1871

Communards pose with the statue of Napoléon I from the toppled Vendôme column, Paris 1871© Musée Carnavalet / Auguste Bruno Braquehais

The more recently heightened sensitivity towards these dubious statues has undoubtedly stemmed from the Black Lives Matter movement, which Quik overtly references. He took the title Meer dan een beeld from a banner that read ‘More than a Statue’ at a demonstration in support of the removal of the statue of the British apartheid architect Cecil John Rhodes from the campus of UCT Cape Town in 2015.

According to Quik, it is unacceptable to maintain symbols that conflict with accepted principles of human rights

In the introductory chapters, Quik discusses the iconoclasm that followed the police murder of black American George Floyd in Minneapolis on 25 May 2020. At that time there existed in the United States more than seven hundred statues of leaders of the Confederacy, the federal state that expanded from 1861 and seceded from the United States in 1865 over fears of a total ban on slavery. The stalwart Confederate generals on horseback were toppled from their pedestals one after the other. The surviving equestrian statue of General Robert Lee in Richmond became the meeting place of anti-racism activists; and scores of light artists projected onto it their own images and texts.

Quik exhibits undeniable sympathy for these anti-racist iconoclasts. Maintaining ‘symbols that conflict with accepted principles of human rights is unacceptable.’ But usually, these relationships are not so black and white. In those cases, alternatives to the extreme options of ‘keep’ or ‘remove’ should be considered. History offers us ample examples from which to learn.

The Van Heutsz Monument in Amsterdam (1935), which in 2004 was transformed from a tribute to the cruel general into a memorial of the Dutch colonial presence in the East.

The Van Heutsz Monument in Amsterdam (1935), which in 2004 was transformed from a tribute to the cruel general into a memorial of the Dutch colonial presence in the East.© Wikimedia Commons

We can look, for example, to the Codex Theodosianus, the collection of legal texts by the Christian emperor Theodosius II from 383 in which fanatical Christians who attacked pagan statues were called to desist. Temples with statues ‘measured more by their artistic value than by their sanctity’ could now remain open, and the trading of these cult figures was no longer considered sacrilege. Space was created for ‘an aesthetic parallel world of collectors and art dealers’.

Something similar happened during the French Revolution. The destruction of monuments that propagated the questionable values of absolute monarchy, however understandable from a revolutionary point of view, was nevertheless regarded as a form of vandalism, as an act that ‘impoverishes and dishonours the nation’ – Quik quotes a proponent of art conservation from the Assemblée Nationale. The revolution developed a new institution to preserve the art treasures while at the same time neutralizing their undesirable ideological implications: the museum.

Still, according to Quik, the removal of statues from the public sphere is not always the best option. Images deemed dubious can remain, provided they are adapted or ‘contextualised’ – for example with commentary upon the changed political or moral valuation of the figure. He sees more value in ‘adding other perspectives, preferably through artistic intervention’.

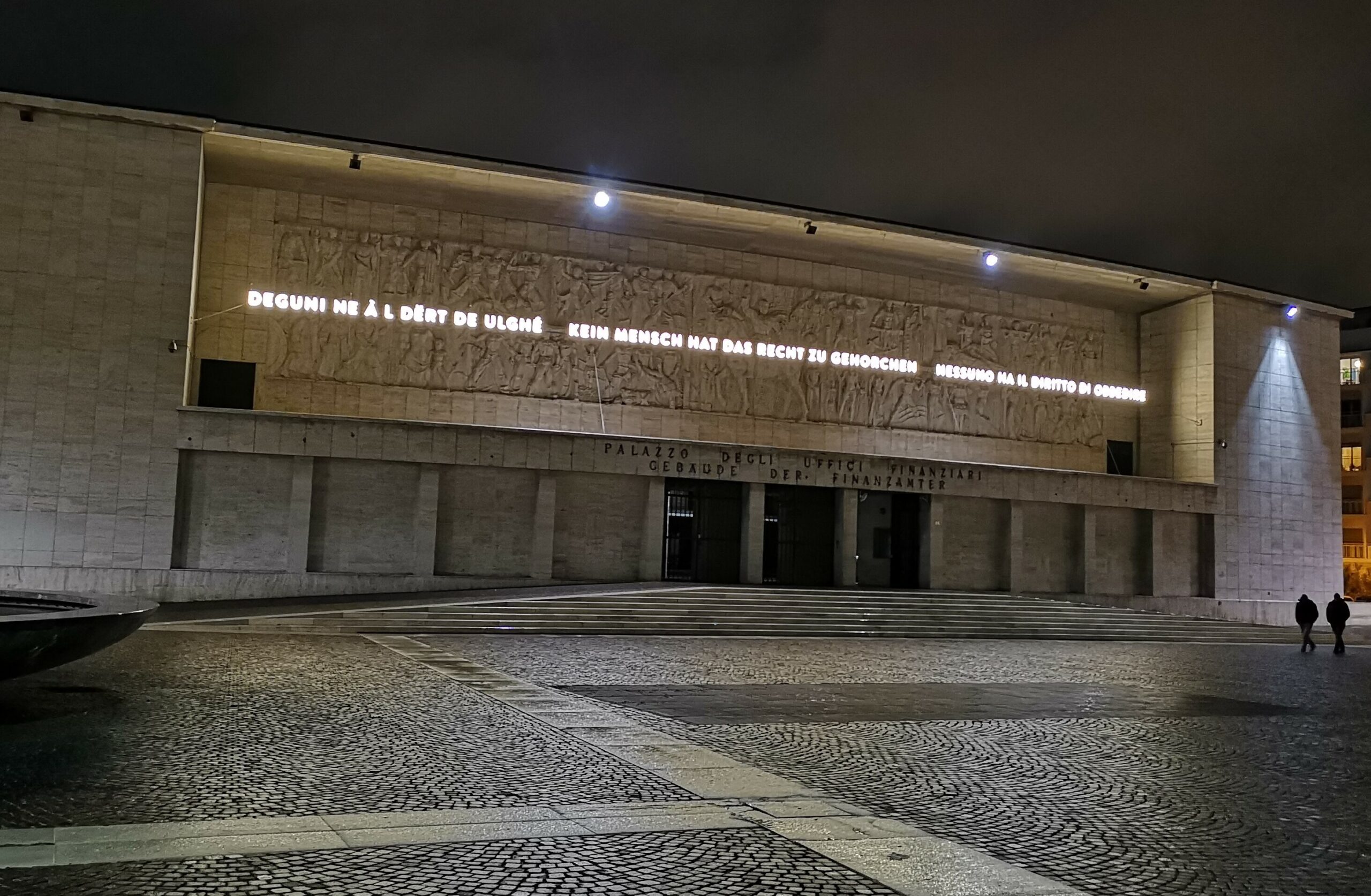

A relief from Casa del Fascio in Bolzano (the former seat of the Italian fascists) which has been newly contextualized by a neon-lit Hannah Arendt quote Kein Mensch hat das Recht zu gehorchen – ‘No man has the right to to obey.’

A relief from Casa del Fascio in Bolzano (the former seat of the Italian fascists) which has been newly contextualized by a neon-lit Hannah Arendt quote Kein Mensch hat das Recht zu gehorchen – ‘No man has the right to to obey.’© Wikimedia Commons

But use cases are not obviously identifiable. Quik mainly refers to examples in foreign countries, like the relief from Casa del Fascio in Bolzano (the former seat of the Italian fascists) which has been newly contextualized by a neon-lit Hannah Arendt quote: Kein Mensch hat das Recht zu gehorchen – ‘No man has the right to obey.’ He also refers to various sculpture parks in Eastern Europe, where Stalinist relics have been erected in a new environment in a sort of open-air museum meets amusement park. Here, ‘initial admiration and unease,’ says Quik, ‘intermingle with contemporary educational entertainment.’

Why don't we bring together controversial statues in a thematic exhibition that delves into the commemoration culture of the nineteenth century?

The Netherlands can certainly learn from these examples: what if ‘we bring together controversial statues (of Jan Coen, of Piet Heyn – and who else?) in a thematic exhibition that delves into the commemoration culture of the nineteenth century.’ But Quik sees the most potential in the transformation of these dubious images: ‘the actualization of a monument in function and design.’ As an example, he cites the Van Heutsz monument in Amsterdam (1935), which in 2004 was transformed from a tribute to the cruel general into a memorial of the Dutch colonial presence in the East.

The closing chapters deal with what Quik calls the ‘new imagery’ that followed the Second World War – the need to embellish our lived-in environments with modern, non-politically motivated sculptures. His informal research into the question of why artworks are placed where they are is also fascinating. He couples this discussion with a trip through Rotterdam, commenting upon work by Wessel Couzijn, Willem de Kooning, Paul McCarthy, Ossip Zadkine and Ben Zegers. It is a shame that his book came out just a touch too soon, so as not to include the rhetoric surrounding the – in my opinion beautiful – new Rotterdam sculpture Moments Contained by the Briton Thomas J Price, which depicts a young, anonymous woman of colour right in front of the station.

Ton Quik, Meer dan een beeld. Gestoorde verhoudingen, IJzer, Utrecht, 2023, 272 pages