Dutch Was an International Language of Diplomacy and Trade

Nowadays, international discussions are mainly held in English, but once upon a time, Dutch played an important role in trade talks and diplomatic relations. In 1856, Russia signed a treaty with Japan that was written in Dutch, Dutch served as a lingua franca around the Baltic Sea for a while and Dutch-language trade documents circulated in the Persian Empire.

People from the Low Countries have always been traders, first in Europe and since the early modern period across the world. They have also needed to carry out diplomacy, building bridges with other parts of Europe and the world. This was above all the case as the Dutch Republic broke away from the Spanish Netherlands, but thereafter, too. To what extent did they use the Dutch language to communicate with others? And was the Dutch language used as a lingua franca by non-native speakers?

Answers to these questions form the basis of this contribution. It does not provide a comprehensive account of the use of Dutch in trade and diplomacy throughout history, but, rather, explores its use in these activities in several regions of the world: Britain, the Baltic, the Muslim world, and Japan.

Great Britain

Given their geographical proximity, over the centuries there has been much trade between Great Britain and the Low Countries. There are reports of seamen from the two areas developing their own ‘mixed’ maritime language, which included many Dutch nautical terms, to communicate with each other.

In the 1600s, each year the Dutch herring fleet would work its way down from the Shetland Islands to the Thames Estuary, with the fishermen going ashore to sell the fish, repair their boats and nets and buy provisions. Some Shetlanders learnt Dutch to communicate with the fishermen. In Great Yarmouth there was a Dutch chapel, which functioned in part to keep the fishermen out of the pubs on a Sunday. English merchants, too, learnt Dutch. Two examples from the seventeenth century are Sir John Elwill from Devon and John Wallis from the port of King’s Lynn. There was little published learning material at this time, and so both men may have learnt the language from native speakers, possibly spending time in the Low Countries.

The Dutch herring fleet, c. 1700, escorted by a naval vessel

The Dutch herring fleet, c. 1700, escorted by a naval vessel© Wikipedia

As for diplomacy, Dutch faced competition from other languages. In 1651, the statesman Jacob Cats addressed the English Parliament in Latin. French, too, played an important role in Dutch diplomacy. Occasionally, however, the Dutch could use their own language in diplomatic relations with England. For example, in 1652, Cats addressed the agent of the Count of Oldenburg, Milius, in Dutch, mixed with Latin.

King William III of Orange

King William III of Orange© Wikimedia Commons / National Galleries of Scotland

It was no doubt during the reign of William III, who ruled England, Scotland, and Ireland between 1689 and 1702, for the first five years as co-regent with his cousin Mary II, that Dutch played a more prominent role in diplomacy with the Dutch Republic.

William himself, who was of course also the Dutch stadholder, was never comfortable with English. He used either Dutch or French; the former in correspondence with the Raadpensionaris, Anthonie Heinsius, and the latter in letters to his favourite, Hans Willem Bentinck.

In 1698, William invited Tsar Peter the Great to England. Peter had already spent time in Holland learning about Dutch shipbuilding and could speak Dutch well. Indeed, he had a Dutch commercial agent, Jan Lups. William seconded an English Vice Admiral, David Mitchell, to the Tsar, as he spoke Dutch.

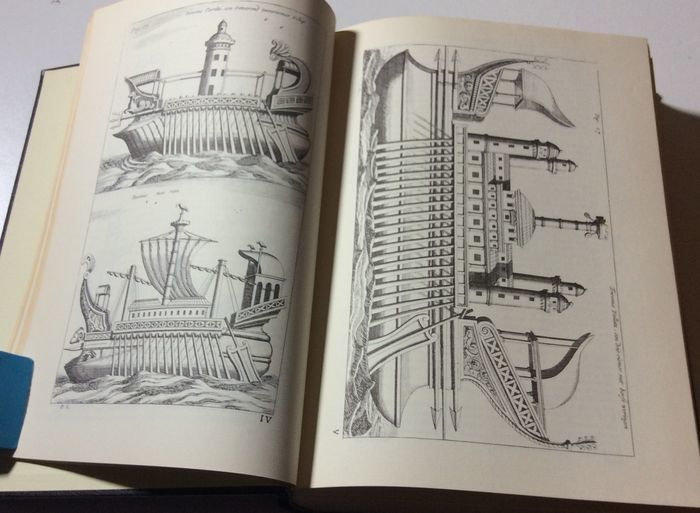

An expert on Russian affairs and shipbuilding, the Dutch statesman and cartographer, Nicolaes Witsen, was a friend of the Russian Tsar Peter I. He wrote a book on shipbuilding: 'Aeloude en hedendaegsche Scheepsbouw en Bestier (1671)'.

An expert on Russian affairs and shipbuilding, the Dutch statesman and cartographer, Nicolaes Witsen, was a friend of the Russian Tsar Peter I. He wrote a book on shipbuilding: 'Aeloude en hedendaegsche Scheepsbouw en Bestier (1671)'.© Catawiki

More recently, above all since the Second World War, English has become the first foreign language learnt by Dutch schoolchildren. Therefore, it is probable that most trade and diplomatic business between the Netherlands and Britain is conducted in English.

The Baltic

Mention of Peter the Great brings us to the Baltic. In the early modern period, many Dutch seamen worked in the Baltic. One consequence of this was that the Dutch language became the lingua franca in the region in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Swedish monarchs, such as King Gustavus Adolfus and his daughter, Queen Christina, knew some Dutch. Gustavus may have spoken the language to his Dutch mistress, Margareta Cabiljau. Christina’s successor, Charles X Gustav, had an English advisor, George Ayscue, who occasionally used his ‘serviceable’ Dutch. Diplomatic correspondence was sometimes written in Dutch and Dutch learning materials and dictionaries were in demand.

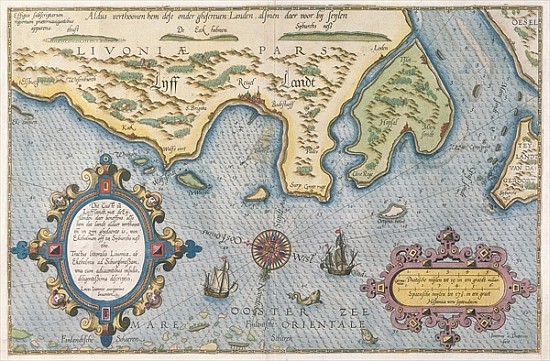

Dutch trade map of the Baltic Sea

Dutch trade map of the Baltic SeaThe leading Antwerp-born merchant, Willem Usselincx, had many dealings with Swedish commercial and political leaders. He and his colleagues wrote to the Swedish Chancellor, Axel Oxenstierna, in Dutch. The Swedish representative to the Dutch Republic, Harald Appelboom, received correspondence from London in Dutch. One of the inaugural lectures of the Royal Academy of Åbo, then in Sweden, now in Finland, was given in Dutch.

Dutch was also used in the military. In peace negotiations between Russia and Sweden in 1618, the Englishman John Merrick wrote to the Field Marshal of Swedish troops in Russia…in Dutch. Given the importance of the language in this region, it is perhaps unsurprising that the States General wrote letters to towns in the Hanseatic League in Dutch.

In peace negotiations between Russia and Sweden in 1618, the English mediator wrote to the Swedish Field Marshal in Dutch

Thanks to Peter the Great’s intensive study and appropriation of Dutch shipbuilding techniques and maritime know-how, many Dutch nautical words were borrowed by Russian and subsequently passed onto other Slavic languages. One example is the Dutch word for ‘sailor’ matroos. The etymologist, Nicoline van der Sijs, writes that this was adopted by Russian as matros and later by Ukrainian and Byelorussian. It was even adopted by other contact languages including Eastern Yiddish and Azeri.

The Muslim world

The Dutch developed extensive diplomatic and commercial relations with the Muslim world in the early modern period. In the early seventeenth century, the Dutch Republic established diplomatic relations with the Sultanate of Morocco and the Ottoman Empire, as they had a common enemy in Spain. Whilst Latin and French were often used in diplomatic contact with Morocco, Dutch was sometimes used in contact with Turkish diplomats and politicians.

One Dutch interpreter who worked in the Ottoman Empire was Jeroen Harder. He arrived in Constantinople in 1673, and in January 1675 was recommended to the States General for the position of interpreter for the Dutch delegation to the Sublime Porte. He would no doubt have had to work alongside some of the large cohort of dragomans, the translator-interpreters employed by the Ottomans to facilitate communication across their Empire and with European states.

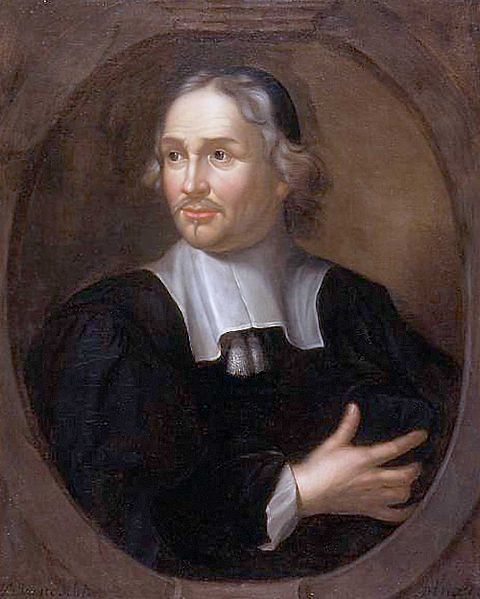

Dutch mathematician and orientalist Jacob Golius

Dutch mathematician and orientalist Jacob Golius© Library Leiden / Wikimedia Commons

Earlier, in the 1620s the scholar Jacob Golius had been in the Middle East. He learnt Turkish and Persian and was temporarily employed in Constantinople as secretary to Cornelis Haga, the Dutch representative to the Sublime Porte. Greece was part of the Ottoman Empire until the nineteenth century. In the mid-eighteenth century, a Greek merchant named Stephano d’Isay was in Amsterdam. He could speak Dutch well enough to act as translator for Greek contractors in the city.

In the Persian Safavid Empire, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) had a trading post at Gamron (now Bandar-e’Abbas), trading above all silk. As elsewhere, VOC commercial documents such as inventories and bills of lading were written in Dutch. Armenians and trading agents called banians often acted as commercial middlemen and some may have spoken Dutch.

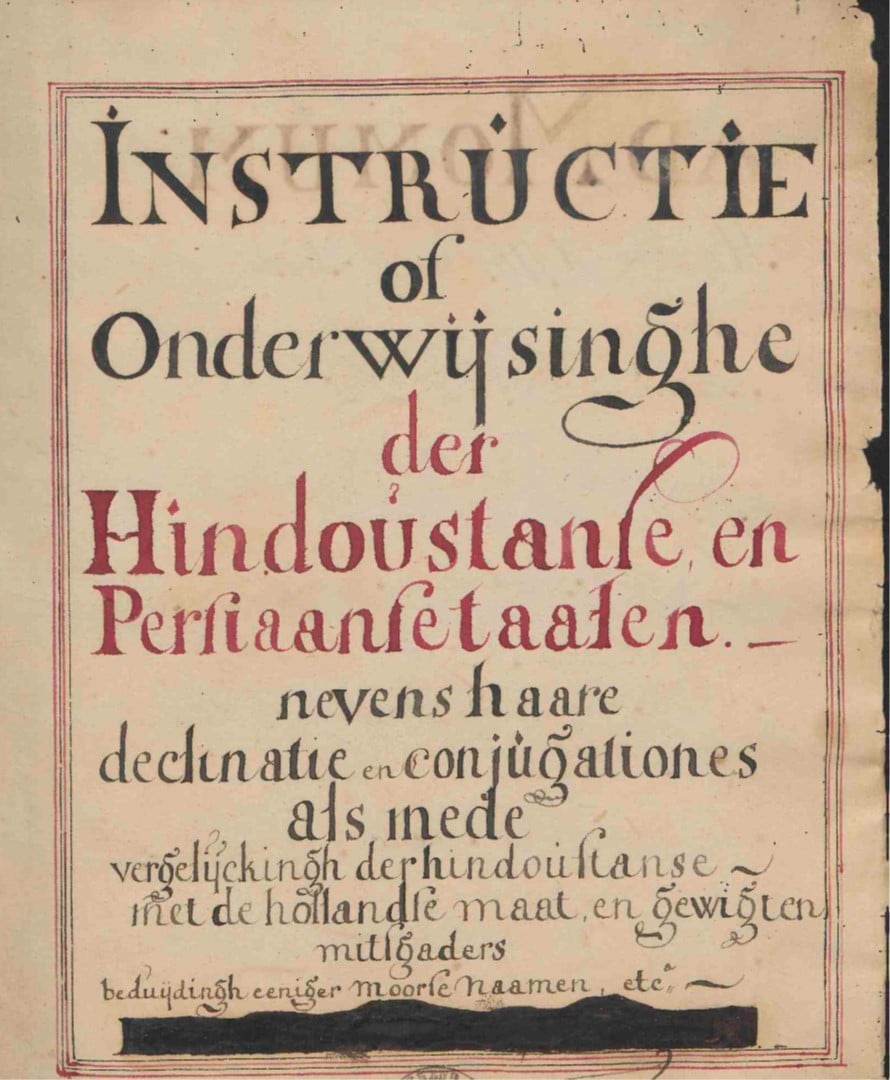

Dutch was the first European language to come into intensive contact with some non-European languages

As a result of VOC commercial activities, Dutch was the first European language to come into intensive contact with some non-European languages in the early modern period. This led to the production of early grammars and lexicons in these languages. One example is the first Dutch grammar of Persian and Hindustani. This was published by the VOC merchant Joan Josua Ketelaar in 1698.

There was a string of VOC trading posts along the Malabar and Coromandel coasts in southern India. The church minister Philippus Baldaeus published his account of the region in Amsterdam in 1672. This included an early grammar of a Dravidian language. The intellectual cosmopolitan Isaac Titsingh was the head (opperhoofd) of the VOC trading post at Chinsura in Bengal in the late eighteenth century. He wrote private and official letters in Dutch which were a riot of code switching into other local and European languages.

Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) was home to some Muslims as well as Christian converts, though the majority of Ceylonese were Buddhist. Between 1656 and 1796, the VOC controlled much of Ceylon, where it had a monopoly on the supply of cinnamon. Dutch was used for commercial activities and was introduced into the schools that the VOC built as a means of making the island in some sense Dutch. However, it made relatively little headway in this regard as the previous colonial power, the Portuguese, had managed to establish their mother tongue as a Language of Wider Communication.

Dutch did, nevertheless, make its mark. Some 230 Dutch loanwords have been identified in Sinhala although some have fallen into disuse. For example, several Dutch commercial terms such as kwitantie

‘receipt’ (Sinhala: kuyitansiya) have been borrowed by Sinhala, as have several words for food such as aardappel ‘potato’ (Sinhala: artapal).

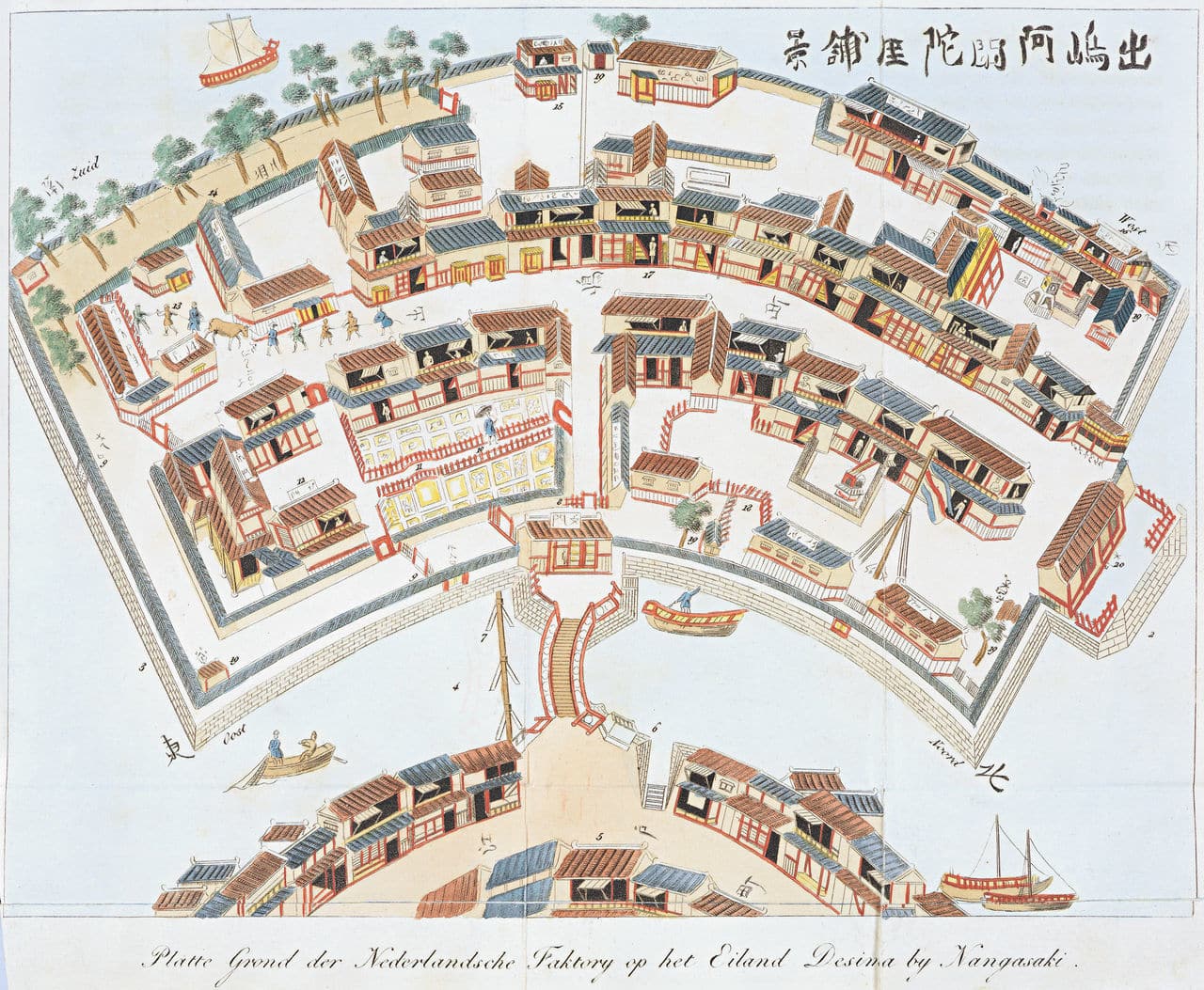

Japan

The first Dutch ship, De Liefde (Love), reached Japan in 1600. The VOC traded with Japan from 1609 until it ceased operations in 1799. Thereafter, the Dutch state traded with Japan. Between 1609 and 1641, the Dutch operated a trading post at Hirado and then on Deshima, an artificial island in Nagasaki Bay. The Dutch were forbidden from learning Japanese and so they had to pay Japanese interpreters to help them communicate with Japanese merchants and officials. The interpreters often learnt Dutch from other interpreters and so VOC employees in Japan frequently complained about their command of the language.

Replica of the galleon 'De Liefde' (Love) in the Japanese theme park Huis Ten Bosch

Replica of the galleon 'De Liefde' (Love) in the Japanese theme park Huis Ten Bosch© Wikimedia Commons / Nissy-KITAQ

Over time, though, the Dutch worked with Japanese interpreters and scholars to produce learning materials that would help improve the interpreters’ Dutch. One important example of this is the Dutch-Japanese Zūfu Haruma lexicon. This was compiled by the head of the trading post, Hendrik Doeff, with the assistance of interpreters. Dutch grammars such as those compiled by Willem Sewell and Matthijs Siegenbeek were imported and re-printed in Japan and other learning aids such as pronunciation guides were produced.

Whilst commercial documents including bills of lading, inventories, correspondence, and the factory journal were written in Dutch, the authors often had to switch into other languages such as Japanese or indeed Portuguese or Chinese to render unfamiliar words. Amongst the Japanese words they had to render in Dutch were types of coin, weights and measures and boats. The Dutch form could be quite different the original Japanese. For example, the unit of length ikken

was rendered by Dutch authors as ickge and the unit of volume koku

as cockjen. The Dutch also gave Dutch names to Japanese associates and Dutch toponyms to Japanese places.

Although the Dutch were in Japan primarily to trade, they were required to perform several diplomatic and political functions. Each year (and every four years after 1790), a delegation of senior Dutch merchants made the journey from Deshima to Edo, now Tokyo, to pay homage to the shogun and thank him for allowing the Dutch to trade with Japan. As in Deshima, communication between the Dutch and the shogun and his officials was facilitated by Japanese interpreters. On one occasion, the shogun asked the senior Dutch merchant, Jan Louis de Win, to write the Dutch words for ‘crane’, spruce fir’ and ‘tortoise’. These are all symbols of long life in Japan. Whilst in Edo, Japanese scholars would visit the Dutch to learn about developments in Western science. This was part of the movement known as rangaku or ‘Dutch studies’.

Map of the Dutch factory on the island of Deshima near Nagasaki

Map of the Dutch factory on the island of Deshima near Nagasaki© Royal Library of the Netherlands, The Hague

Book of rumours

Between 1640 and 1854, the Dutch were the only nation outside East Asia permitted to trade with Japan. Furthermore, Japanese were not allowed to leave the country. The Dutch therefore provided a window onto the wider world for the Japanese. Each year they had to write a report on events outside Japan. This report was compiled in Dutch and translated into Japanese, with the title Oranda fūsetsugaki or ‘Dutch book of rumours’. From 1840, after the outbreak of the First Opium War (1839-42), the Dutch wrote an additional report which was translated into Japanese with the title Betsudan fūsetsugaki (‘Special [Dutch] Book of Rumours’), This analyzed the impact of the war on East Asia.

Between 1640 and 1854, the Dutch were the only nation outside East Asia permitted to trade with Japan

The privileged position of the Dutch ended in 1854, when the Americans forced the Japanese to trade with them. Other Western countries such as Britain, France and Prussia soon followed and in 1860, the Dutch closed their trading post at Deshima. However, the Dutch language in Japan did not immediately go into decline, for it was used as a language of diplomacy between the Japanese and Western diplomats. In 1856, Russia concluded a treaty with Japan written in Dutch. A treaty between Japan and Belgium concluded in 1866 was written in Japanese, French, and Dutch. Although French was then the dominant language in Belgian public life. the Dutch version was given legal priority in case of doubt. Dutch was also used in negotiations between the Japanese and Italy, Siam, Portugal, and Prussia. In 1868, the Meiji Restoration heralded a new era in Japan and the use of Dutch declined rapidly in favour of English, French, and German.

Finally, Japanese has borrowed over 300 Dutch words. The Dutch introduced many new items including food and drink into Japan. Indeed, the Japanese words for ‘beer’ and ‘coffee’, bīru and kōhī, are derived from the Dutch bier and koffie. The Dutch word koffie in turn is derived from the Ottoman Turkish kahve, possibly via Italian.

Ultimately, Dutch has not become a world language like English or Spanish. But as has been shown, the language did leave its traces in other languages. Above, we mentioned examples of lexical borrowings in Russian, Sinhala, Japanese, English and Mandarin Chinese. These borrowings are mainly the result of the extensive commercial contacts between native speakers of Dutch and other languages in the world.

This article was realised with the support of the Nederlandse Taalunie (Dutch Language Union).