The Ambiguous View Of Sexuality In The Low Countries

Since 1945 the Netherlands has often been a frontrunner on the world stage when it comes to sexuality. Belgium is usually quick to follow. But a certain sense of unease has always lingered and seems to be growing these days.

Today’s world is one of comparative rankings. The 2022 World Index of Moral Freedom, in which gender and sexuality weigh heavily, puts the Netherlands in second place, Belgium third and Luxembourg sixth. On the Rainbow Index of 2022, which charts the rights of non-heterosexuals, Belgium ranks third, Luxemburg joint fourth and the Netherlands ninth.

Lists like these are indicative at best, but still show that the Low Countries are amongst the most liberal in the world in terms of sexual rights. Today this no longer comes as a surprise, but from a historical point of view, it remains a remarkable and, all in all, recent development. After all, before the Second World War Belgium and the Netherlands were deeply religious and sexually conservative societies, in which only small minorities dared to preach change.

Joy on the Dam Square at the liberation of Amsterdam. For a moment, the war and liberation seemed to cause a sudden upheaval in dealing with sexuality.

Joy on the Dam Square at the liberation of Amsterdam. For a moment, the war and liberation seemed to cause a sudden upheaval in dealing with sexuality.© Spaarnestad Photo / Wiel van der Randen

For a short while, the war and liberation did seem to cause sudden radical change. Alarming statistics concerning the rapid spread of venereal disease accompanied the charming photos of young women in the arms of allied soldiers. “Horizontal collaboration” during the war also had a great symbolic impact, so the Belgian and Dutch authorities rapidly mobilised the population against moral degradation.

As a result, the 1940s and 1950s were dominated by this struggle against the moral degeneration of the young. The police, public prosecutors and policymakers were obsessed with increased juvenile delinquency. In addition, a disproportionate amount of attention was paid to prostitution and homosexuality, two phenomena that people liked to attribute to the cynical pursuit of profit by corrupting adults, in the form of pimps and pederasts. In practice, this climate of fear translated into a strong emphasis on family values, traditional gender patterns and patriarchal authority.

The 1950s: more interesting than they seemed

Nonetheless, it would be wrong to regard the 1950s simply as a mere conservative spasm preceding the more progressive 1960s. At the time, the liberal humanist movement played a leading role in both countries in advocating for more individual self-determination. In terms of sexuality, however, this was still very limited. Somewhat more pronounced were the movements for sexual reform with close links to humanism. The Dutch Association for Sexual Reform (NVSH) took the lead. Since 1946, it had focused mainly on offering sex education on contraceptives, in clinics set up for that purpose.

It would be wrong to regard the 1950s simply as a mere conservative spasm preceding the more progressive 1960s

Following suit, the Belgian Association for Sexual Reform saw the light of day in 1955. Both organisations operated in a legal grey zone. The religiously inspired morality laws of 1911 prohibited the “open” provision of information on contraceptives in the Netherlands. Similar laws have existed in Belgium and several other European countries since 1923.

As early as the 1950s a fledgling gay movement emerged in the Low Countries. The Netherlands was a pioneer in that, too. Already in 1912, the Dutch Scientific Humanitarian Committee (NWHK) was founded there, a spin-off of the movement to decriminalise homosexuality led by the doctor and activist Magnus Hirschfeld, in Germany. The recently implemented increase in the age of sexual majority for homosexual contacts in the Netherlands – also part of the 1911 morality laws – had everything to do with it. Just after the Second World War, the committee had a breakthrough, with the establishment of the Shakespeare Club in Amsterdam. A few years later it was renamed Culture and Relaxation Centre (COC). This euphemistic name betrays the fact that the initially small organisation was closely watched by the police and had to do everything it could to present itself as a respectable social club.

Belgium lagged a bit behind in the fray. This was largely because there had been no explicit criminalisation of homosexuality there since the French Revolution so, unlike in the Netherlands and Germany, there was no clear issue around which homosexual men and women could organise. After contact with the COC, the gay Centre Culturel Belge was established in Brussels, in 1953.

As early as the 1950s a fledgling gay movement emerged in the Low Countries

The religious-conservative climate of moral restoration in the post-war years explains why the organisations mentioned above remained small at first and had the greatest difficulty surviving. During the same period, however, even the churches began an important transformation in terms of marriage morality. In Protestant-dominated Northern Europe and North America, a theological and pastoral liberalisation movement was underway. In 1952, for example, the Dutch Reformed Church decided that birth control would, in future, be a matter for couples to decide for themselves. This was not at all to the Vatican’s liking, but within the Roman Catholic Church, too, there was debate about procreation as the main purpose of marriage. Was not love between spouses – and sexuality as an expression of it and means to that end – not at least as important?

At the same time, there was also confusion and debate about periodic abstinence, which Pope Pius XI had authorised under unclearly worded circumstances, in 1951. Faced with a huge baby boom among the population, which had suffered severely during the war, many confessors in Belgium and the Netherlands found it less and less natural and even less desirable to demand strict obedience to the precepts of the Church. When, during the late 1950s, the development of the contraceptive pill (in which the Low Countries played an important role) gained momentum, the genie was definitely out of the bottle.

Moreover, several broader social developments were increasingly influencing the debate on sexuality in particular. With the Cold War, the influence and standing of the United States had increased at a staggering rate. Culturally, its influence was perhaps most felt in the influx of corny Hollywood films, exciting children’s literature and provocative music. Conservative voices were very concerned about the pleasure-seeking and individualistic value pattern emanating from them.

The 1960s and 1970s: gathering momentum

During the late 1950s, the combination of an unprecedented economic boom and the expansion of the welfare state also created a historically new phenomenon, that of non-working adolescents with money and free time. They were constantly tempted by a growing leisure and entertainment market that increasingly understood that sex sells. Jeans and leather-clad nozems, as the Dutch referred to them – rebels without a cause as far as the general public was concerned – were the embodiment of the much-discussed debauchery of postwar youth.

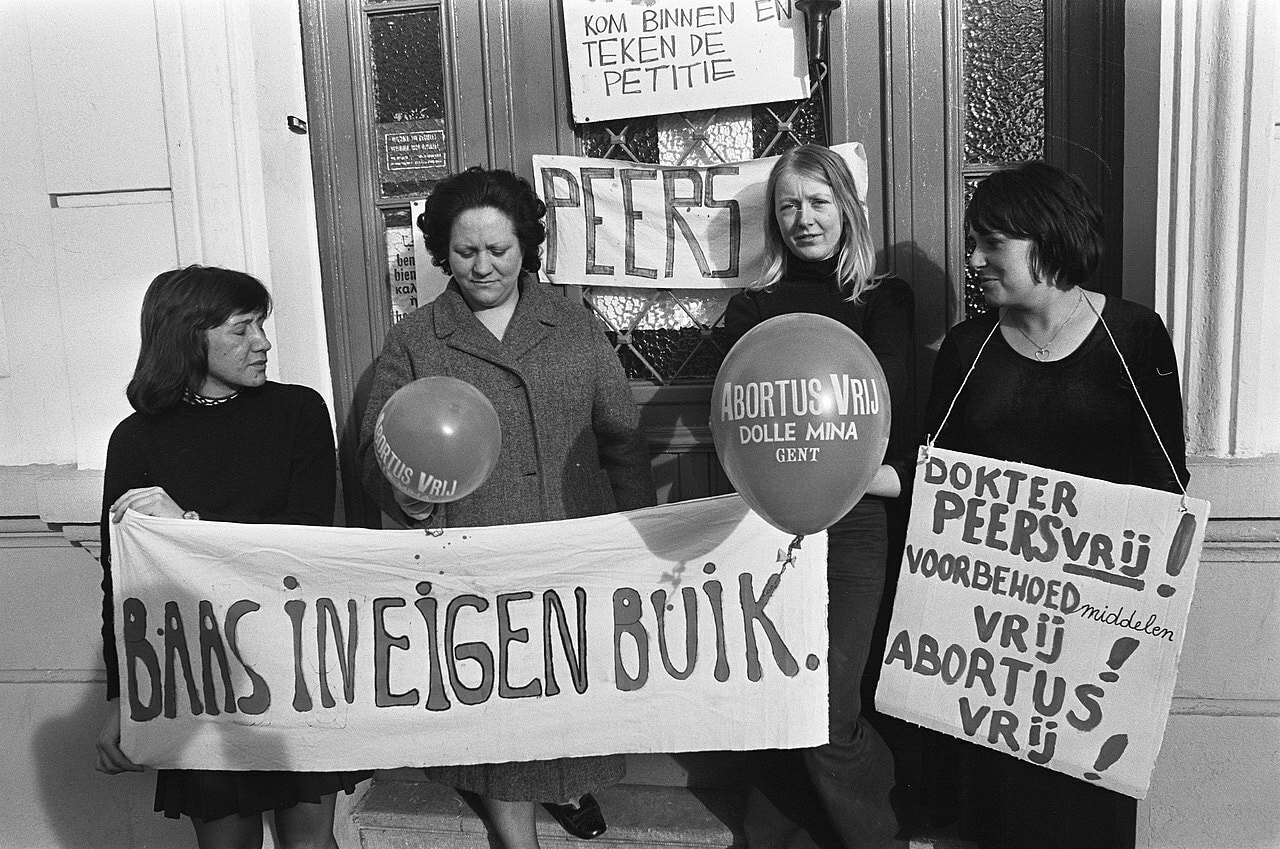

The Dolle Mina's (Dutch feminist group) hold a hunger strike in Ghent in 1973. They are demonstrating for the release of Dr. Willy Peers, an advocate of abortion and contraception.

The Dolle Mina's (Dutch feminist group) hold a hunger strike in Ghent in 1973. They are demonstrating for the release of Dr. Willy Peers, an advocate of abortion and contraception.© Anefo / Bert Verhoeff

By the mid-1960s, these baby boomers were ripe for the universities, which were soon bursting at the seams. There, many learned about the great injustice in the world: about the civil rights movement in the United States, the war in Vietnam and the hypocrisy of the self-satisfied West. This often led to the glorification of anything that was non-Western or anti-capitalist. Radicalism and revolution were the order of the day. That broader climate of contestation was increasingly evident in anything to do with sexuality. In the fierce protests of 1968, which were much fiercer in Belgium and elsewhere than in the Netherlands, sex was still not a major issue. But shortly afterwards women’s movements like Dolle Mina (“Mad Mina”) emerged, women who wanted to become the “boss of their own belly” through the legalisation of abortion.

In both of the Low Countries, radical feminists were considered the most prominent exponents of the sexual revolution during the 1970s. Increasingly visible, too – but less numerous – were the left-wing radical gay and lesbian movements like Rode Hond (“Red Dog”), Paarse September (“Purple September”) and Rooie Flikkers (“Red Faggots”). But, as important as they were, their activism should not obscure the fact that there were also broader social shifts occurring at the same time. Their struggle soon became a primarily rearguard action. For example, the courts recognized that the “public morals” they guarded were no longer what they used to be. And, when the pornography legalised in Scandinavia became available in the Low Countries in the late 1960s, the boundaries of what was considered obscene were pushed back once and for all – especially in the more liberal Netherlands. Meanwhile, opinions on contraception, sex education and premarital sex were shifting too. What had previously been considered the libertarian ideas of a small circle of sexual reformers became the new social consensus in the late 1960s and 1970s.

What had long been considered the libertarian ideas of a small circle of sexual reformers became the new social consensus in the late 1960s and 1970s

This set the first of two major postwar liberalisation movements in motion. The Netherlands was an international pioneer when it equalised the age of sexual majority for homo and heterosexuality, in 1971. In Belgium it would take until 1985. In both countries, the pill had appeared on the market in the early 1960s, and its use was increasing at a spectacular rate. Few things have had a more powerful effect on changing sexual practices than the availability of reliable contraceptives. That women gained more control over their own fertility was a major development. In 1969 and 1973 respectively, bans on the provision of information and commercialisation of contraceptives disappeared in the Netherlands and Belgium.

Abortion was more contentious, but practice was increasingly ahead of the law, and its conditional liberalisation in the United Kingdom, in 1967, served as an example. An abortion law was passed in the Netherlands in 1981 and actually took effect three years later. In Belgium, the debate led to a constitutional crisis, when the deeply religious King Baudouin refused to sign the abortion law that was adopted in 1990. Nonetheless, the law was enacted when the King abdicated for a day – an expedient solution.

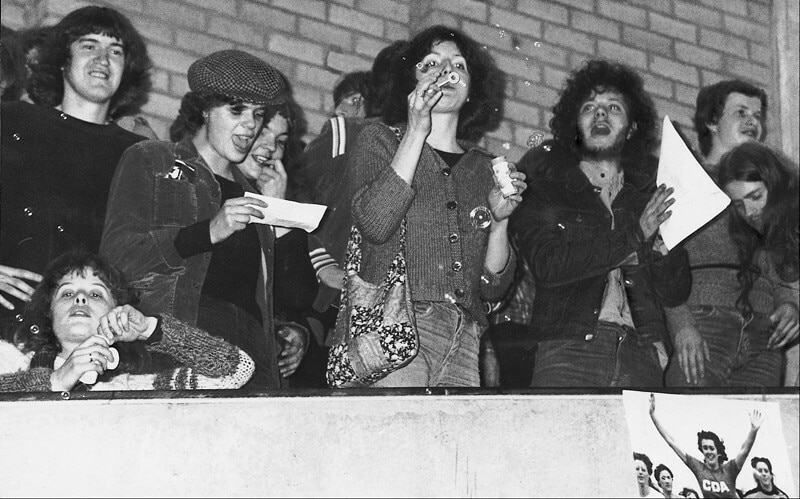

In the 1970s, radical left-wing gay and lesbian movements such as Rooie Flikkers (Red Faggots) became increasingly visible.

In the 1970s, radical left-wing gay and lesbian movements such as Rooie Flikkers (Red Faggots) became increasingly visible.© Liesbeth Sluiter

A second wave of liberalisation

The late 1970s and 1980s were marked mainly by austerity and economic crisis. In the United States and the United Kingdom, political and social reaction against the more progressive 1960s and early 1970s went hand in hand. This manifested itself in the emergence of organised anti-abortion and anti-gay movements. The latter was boosted by the panic created by a mysterious and deadly new disease that was spreading fast, especially among homosexual men: HIV/Aids. In Belgium and the Netherlands, there was a similar reaction, but it remained much less explicit. The disease itself was disastrous for the LGBTQI+ community. More broadly, too, issues of gender and sexuality were not policy priorities during this period.

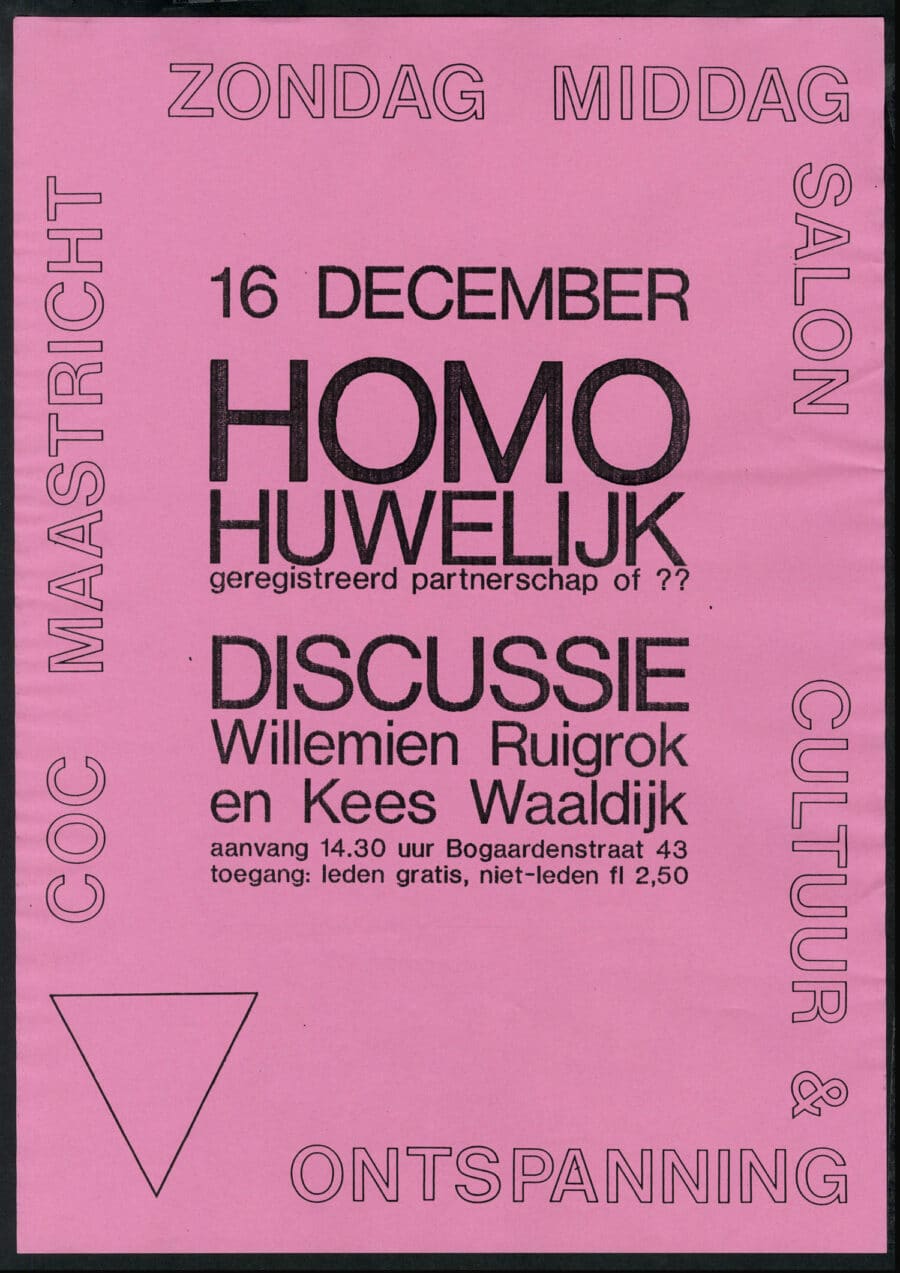

Poster from 1990 for a debate on same-sex marriage. It would take more than a decade before it became possible.

Poster from 1990 for a debate on same-sex marriage. It would take more than a decade before it became possible.© International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam

During the 1990s, once again first in the Netherlands, a new wind began to blow with the formation of ‘purple’ (socialist/liberal) governments which, for the first time in many years, did not include the Christian Democrats. This launched a second wave of liberalisation which translated, starting with registered partnerships in 1998, into same-sex marriage in 2001. Belgium, which formed a government without Christian Democrats in 1999, made same-sex marriage possible in 2003. In its wake there followed (further) liberalisation of gay adoption, the rights of trans people to change their gender identity, and powerful anti-discrimination laws.

Ambiguous legacy

In retrospect, the last seventy-five years seem to have brought a lot of changes in terms of sexuality. Yet their legacy remains ambivalent. These days, the debate about sexuality is – no less than it was before – surrounded by a sense of unease. Central to this is often the vulnerability of minors in a highly sexualised society. In the 1990s there was the Dutroux affair in Belgium. More recently, the population was shocked by the revelations concerning the abuse of children by priests.

Civil wedding of two men in Amsterdam in April 2001, the first month in which the Netherlands made it possible - the first country in the world to do so.

Civil wedding of two men in Amsterdam in April 2001, the first month in which the Netherlands made it possible - the first country in the world to do so.© Wikimedia Commons

In 2023, parents are struggling with the ubiquitous presence of pornography and grooming (sending sexually charged messages and images) on the internet. Consent became a hot topic when studies indicated how many people – especially women, gay and trans people – fall prey to sexual intimidation and violence.

As pressure groups push for more rights – for intersex people, for example – more and more voices on the right call for a halt or even reversal of these rights. The internationally organised reaction against a liberal and secular conception of sexuality has never been stronger than today, even in Europe. In the Low Countries, the liberal view remains dominant for now, but contestation is growing. As far as views on sexuality are concerned, a lot is going on, and it is far from clear which direction Belgium and the Netherlands will go.