You Are What You Smell: How Scent and Culture Are Intricately Linked

What did the past smell like? And how does scent influence our culture? Questions like these are getting more attention in the field of (art) history research. Biologist and philosopher Geerdt Magiels takes us along on a visit to Fleeting – Scents in Colour at the Mauritshuis, to the stinking seventeenth century and to the nearly scent-free Low Countries of today.

Scents are invisible, but they are all around us, everywhere. They colour our lives and give depth to the world. They form a completely permeating dimension to reality, both in the past and present. And yet we have long been unaware of their importance. We quickly become used to any continuing scent (even if it stinks), such as the smell of our own bodies or that of a household pet. While we can close our eyes to give them a rest, we can’t close our noses.

De Reuk (The Smell), Pieter Jansz Quast (possibly), after Pieter Jansz Quast (1615-1647)

De Reuk (The Smell), Pieter Jansz Quast (possibly), after Pieter Jansz Quast (1615-1647)© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

We seldom realise that we are continuously processing a range of scents until a scent we’re not familiar with drifts into our noses. Or until we lose our sense of smell, perhaps from being infected by a virus. Anosmia, loss of the sense of smell, was a symptom in more than half of the COVID infections, which made many people realise just how drastic that loss can be. Without a sense of smell, we can no longer enjoy the aromas of food and drink, which is what makes them so tasty. Taste is essentially smell. That’s why food seems to lose its flavour when your nose is blocked, for example, by bad cold.

We catch scents when light, volatile molecules escape and make contact with our nervous system in the odorous epithelium at the top of the nasal cavity. Every smell is a fusion of a molecule from the outside world with the inside world of our bodies: whatever we smell becomes part of ourselves. So we are what we smell. The scent receptors connect directly to the feeling and memory circuits in the brain, which explains the enormous emotional impact some scents can have on us. A smell can make us gag, but it can also transport us back to places or times in our memories.

The emotional impact of scents, and how we value them, is largely culturally determined, though the context of smells also determines their meaning. Consider how the smell of tobacco was once a sign of luxury and pleasure. Or how frankincense and other incenses symbolise prayers ascending to heaven.

Scents in colours

How culture and smell are closely linked can be seen – and smelled – in a fascinating exhibition at the Mauritshuis in The Hague. Fleeting – Scents in Colour explores the role of scent in seventeenth-century art. The compilers searched paintings, drawings and objects to create a scent palette for the era and have provided eight ingenious “smelling stations” where visitors can sniff the reconstructed scents of that time.

This multi-sensory presentation responds to a reawakened interest in scent and our ability to detect it. For a long time, the scientific focus of neuro research has primarily concerned the human ability to see, not least because this is relatively easy to study. How, exactly, we are able to smell, however, has long remained a mystery.

In her book Smellosophy

(2020) science historian Ann-Sophie Barwich explains how the three hundred and fifty different receptors in the millions of nerve endings of the nasal epithelium detect the world’s olfactory richness. Each scent is a mixture of often dozens of different molecules that are transformed into a “fragrance image” rich with cognitive and emotional associations.

Author Harold McGee follows a molecular path in his monumental book The Scents of the World (De geuren van de wereld (2021). He links molecules and their organo-chemical properties to smell and taste effects in the brain and takes readers on an encyclopaedic journey through the “osmocosm” where he interweaves molecular structures with geography, biology and history. (Don’t be alarmed by the encounters with terpenoids or furanone along the way.)

We are right at the start of a scent renaissance. For example, the 2.8-million-euro project Odeuropa was launched early this year. This is a project in which (art) historians, linguists, scent makers and experts in artificial intelligence join forces and, using digital search engines, track down scents recorded in four centuries-worth of digitized texts and seven languages. Their mission: to imitate early modern olfactory experiences. Heritage researchers extract the scents of old books and leather gloves while perfume labs and museums work together to recreate the scents of the past.

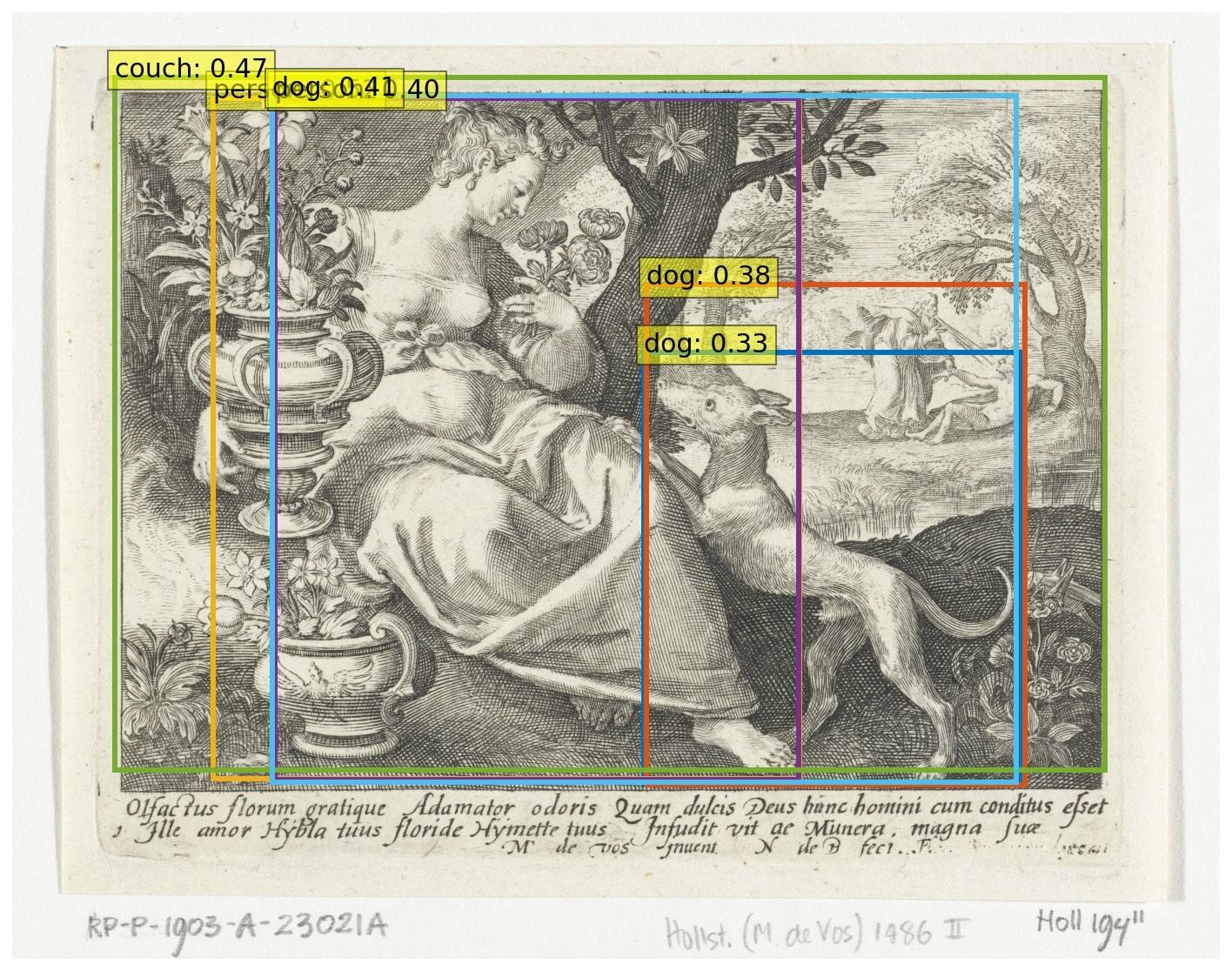

In the research project Odeuropa, scientists look at how smell is represented in works of art, such as here in 'Zintuig reuk' by Nicolaes de Bruyn (1581-1656).

In the research project Odeuropa, scientists look at how smell is represented in works of art, such as here in 'Zintuig reuk' by Nicolaes de Bruyn (1581-1656).© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

What a stench!

The seventeenth century had an intense scent palette. It seems likely that the stench was barely tolerable. In 1666, the French satirist Pierre Le Jolle addressed the Amsterdam canals as “vostre illustrissime saleté” (Your Illustrious Filth). The canals that crossed the cities were effectively stinking, open sewers, especially in warm weather. Excrement, animal carcasses, garbage and rotting food scraps floated in them. Sewer systems and running water were non-existent. Food rotted in the absence of refrigerators.

Bathing and teeth-brushing were not common, hygiene was pretty much limited to trying to conceal body odours through the use of pomanders, luxurious showpieces in which the rich carried scented substances (the name comes from pomme d’ambre, after the ambergris extracted from the stomach of sperm whales). All in an attempt to drown out the pungent smells of tanned leather (footwear and gloves).

Pomander, probably Northern Netherlands, c.1620. Silver and silver-gilt, h. 6 cm

Pomander, probably Northern Netherlands, c.1620. Silver and silver-gilt, h. 6 cm© Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede (on loan from the Martens-Mulder Foundation)

Urine was collected in barrels for use in tanning hides and dying and fulling fabrics. The fumes from bleaching fields, lime kilns, whale-oil refineries and tanneries could be smelled miles away. Linen was bleached with sour buttermilk and caustic potash liquor, resulting in a truly pungent odour. The bleaching fields were, in fact, banned from the city limits whenever possible. And there were also the gallows fields, where the hanged lingered as fodder for crows and rats and signalled that the town was tough on crime. The smell of rotting corpses was a sort of scent flag that marked the city council’s territory.

Anatomy lessons in medical faculties were only given in the winter but were, nonetheless, olfactory torture. In the winter, wood or peat was burned for heating. Good stoves had yet to be invented and houses were very smoky – which might have been a small advantage, as the smoke masked the other scents. And outdoors wasn’t much better. The air hanging “above all the great cities” was “often filled with smoke-vapour […]”, according to historian Tobias van Domselaer. A city could be smelled from afar, sometimes hours before arriving there.

Jacob van Ruisdael, View of Haarlem with Bleaching Grounds, c.1670-1675

Jacob van Ruisdael, View of Haarlem with Bleaching Grounds, c.1670-1675© Mauritshuis, The Hague

Rich people fled to houses in the country to escape the incredible stench, especially in the summer months. The poorest neighbourhoods were, and often still are (in the western hemisphere), downwind, on the east side of the city. Traces of this urban planning tactic can still be seen on maps and these areas are often those with the lowest socioeconomic status. In the countryside, a steaming, fragrant dunghill was a sign of wealth and fertility.

Sick air

There was a belief that bad smells caused sickness so the link between dirt and disease could not be ignored. Malaria illustrates this idea perfectly: “mal aria” is bad air, the miasmas rising from swamps, cesspools or rotting carcasses.

In the eighteenth century, one of the first tools used to take chemical measurements was the “eudiometer,” which indicated the “goodness” of the air and provided a visible measurement of the amount of oxygen in an air sample. Although “oxygen” as a chemical concept was not yet understood, people already knew that a certain gas (“dephlogisticated air”) could make a flame burn longer and more intensely and keep a mouse or bird alive longer under a glass dome.

Michiel and Pieter van Mierevelt, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Willem van der Meer, 1617

Michiel and Pieter van Mierevelt, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Willem van der Meer, 1617© Museum Prinsenhof, Delft

Alongside his other activities, the Brabant physician and researcher Jan Ingenhousz, who discovered the process of photosynthesis, perfected the technique and took measurements in prisons and market halls, in cities, at sea and in forests, at ground level and up church towers, always on the hunt for better air.

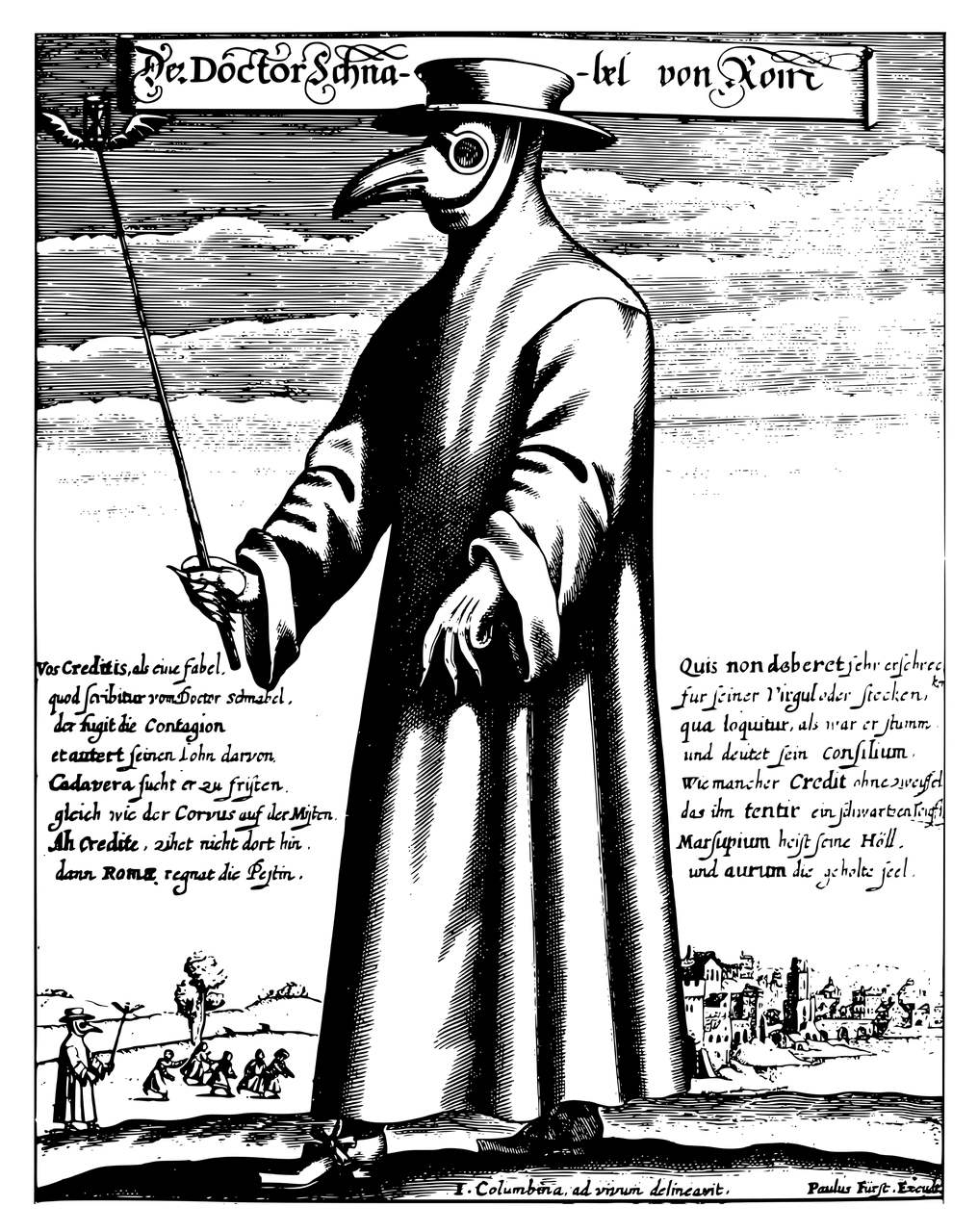

It was, of course, not the stench that caused illness; rather it was likely that gases making up the smell are what made people feel unwell. It would be another hundred years before parasites or micro-organisms were recognised as the causes of disease. Meanwhile, the protective clothing worn during plague epidemics may have served its purpose. The closed suits of boots, hats, gloves and masks prevented transmission, much as proper PPE does in today’s pandemic.

In addition to a vinegar-saturated sponge, the bird beaks of the masks contained mixtures of dried flowers (such as roses and carnations), herbs (such as lavender and peppermint), camphor, juniper, ambergris, cloves, labdanum, myrrh, and storax. They probably did little more than drown out the stench of the festering wounds. Perhaps the stick used by the plague masters was the most effective in keeping the sick and disease at bay.

Plague master

Plague masterIn contrast to the seventeenth century, our society today is largely “deodorised”. Of course, we can still catch a scent on the street: the launderette on the corner, a passing smoker, a chip shop or fresh bread from a bakery. But to experience a truly fragrant urban landscape it is necessary to visit tropical megacities such as Lagos or Mumbai, where aspects of our former living conditions still prevail.

In the Low Countries, our lives are almost unnaturally stink-free. Rubbish is collected regularly, sewers and water purifying plants function properly, catalytic convertors ensure a cleaner exhaust and refrigerators keep food from going off as we opt for water-soluble, scent-free paint. (Of course, scent-free doesn’t mean completely safe: DDT and PFOS are odourless.) Artificical scents have taken over. Detergents, deodorants, perfumes and soap dominate the natural odours in the background. It has become rather difficult to find unscented loo rolls or other household products free from artificial additives.

Even the smell of roses has disappeared. Today, they are primarily selected for their showy blooms at the expense of their intense scent. And this while “scent events” focusing on scent marketing in retail spaces try to create an atmosphere that entices customers to stay longer and buy more.

Noses first

Smell is the primal sense. Unicellular organisms detected molecules in the environment and orientated themselves towards food sources or away from perceived danger using smell before hearing or seeing anything. Millions of years later, scent is still the primary signal of possible danger for animals and, therefore, also for humans. Sweet and pleasant scents are attractive, stench indicates spoilage, disease, death. Scavengers are, of course, drawn to the rottenness, but for the rest of us, the smell of a ripe, stinky cheese or surströmming (fermented herring) generally has to be overcome before we are willing to take a bite or develop a taste for it.

Despite the pervasiveness of scents, we have few words for them. There are hundreds of words for specific visual or auditory sensations, but remarkably few words pertaining to smell. Perhaps this is because smell is so difficult to quantify whereas light and sound waves can be accurately measured. When we want to name a scent, we usually refer to something it smells like.

A scent is therefore always part of something else and, as a result, scents are never far away. Our fragrance environment is a cultural landscape that evolves along with fashions, styles and standards and helps determine who we are. In short: scent is an irrevocable part of the human story and is beginning to receive the attention it deserves. When Andy Warhol wished, in 1975, for “some kind of smell museum, so certain smells wouldn’t get lost forever” his desire went unfulfilled. Today, the exhibition at the Mauritshuis is just one of the many (museum) initiatives that are teaching us to newly value our sense of smell.

- Vervlogen – Geuren in kleuren, until 29 August at the Mauritshuis, The Hague. You will be able to experience this exhibition at home even after it has ended.

- The Mauritshuis is pioneering an interactive smell and look tour. Culinary journalist Joël Broekaert and curator Ariane van Suchtelen take the viewer on a virtual tour, while you can sniff out certain scents from the exhibition with four inventive pumps from a scent box that can be ordered through the museum.

- Barwich, A.S. Smellosophy. What the Nose Tells the Mind, Harvard University Press, 2020

- McGee, Harold, De geuren van de wereld. De ultieme gids voor alles wat we kunnen ruiken (original title: Nose dive. A field guide to the world’s smells), translated by Jacques Meerman, Nieuw Amsterdam, 2021

- Muchembled, Robert. La civilisation des odeurs, Les Belles Lettres, 2017