Without a Book of Hours, You Were at the Mercy of Fate in the Middle Ages

Books of Hours could be found in almost every late medieval household: talismans full of prayers, songs, and miniatures. The most beautiful ones were incredibly expensive. The Groeningemuseum in Bruges is showcasing a unique collection.

In the autumn of 2024, the fantastic exhibition Medieval Women in Their Own Words at the British Library in London was jam-packed. With great effort, you had just enough time to lean over the display cases before someone impatiently nudged you in the side. Inside those display cases were beautifully stacked Books of Hours. These are small books full of prayers against diseases or for safe delivery during childbirth. Or simply to draw comfort from.

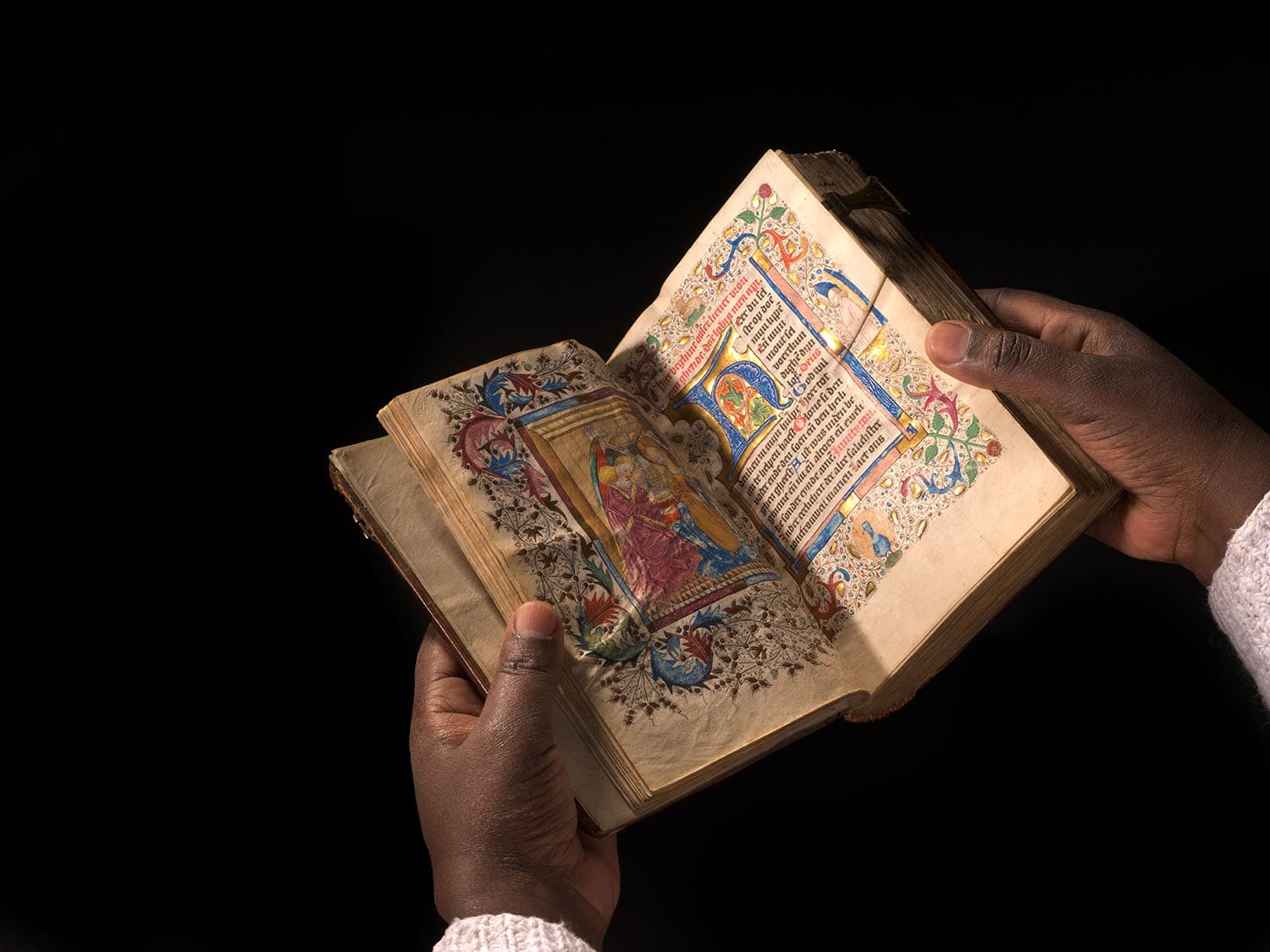

Book of Hours (translation by Geert Grote), Master of the Haarlem Bible, Haarlem (?), ca. 1460–ca. 1480

Book of Hours (translation by Geert Grote), Master of the Haarlem Bible, Haarlem (?), ca. 1460–ca. 1480© Public Library of Bruges

In Flanders, medieval treasures are also popular. They are even worth an investment: in 2023, the Flemish government purchased a thirteenth-century psalter (book of psalms) and a fifteenth-century book of hours from the old County of Flanders and entrusted them to the Public Library of Bruges. Both manuscripts are on display in the exhibition Pride and Comfort: Medieval Books of Hours and Their Readers at the Groeningemuseum in Bruges. Several copies from the private foundation of the noble family Caloen are also shown to the public for the first time.

Mealtime prayer time

Yet prayer books have always been present in our museums. When you walk through the medieval collection of any fine arts museum in the world today, there is a good chance that you will find fifteenth-century panels featuring kneeling men and women holding a booklet in their hands or on their laps. It shows how meaningful prayer books were for medieval readers, how much they were part of their daily lives.

Some copies are modest, made for mass production, while others are unique masterpieces. We find them among all layers of medieval society (clergy, nobility, bourgeoisie, and craftsmen), but primarily among the wealthy class. Readers took pride in their expensive and beautifully decorated copy, for which they were willing to spend their last savings. In the most difficult moments of their lives, they drew comfort from the prayers.

The prayers were read aloud, just like most books in the Middle Ages. It was normal to read aloud even when alone

The core of a Book of Hours consists of the so-called “Hours”: prayers that monks and clerics recited at fixed times. Usually, these were divided into eight prayer times. At midnight, the Matins or Vigil began, around three in the morning the Lauds, around six the Prime, around nine the Tierce, at noon the Sext, around three the None, around six or at sunset the Vespers, and around nine or before bedtime the Compline. Some of these prayer times linger in our spoken language: think of “Noon” for (after) noon.

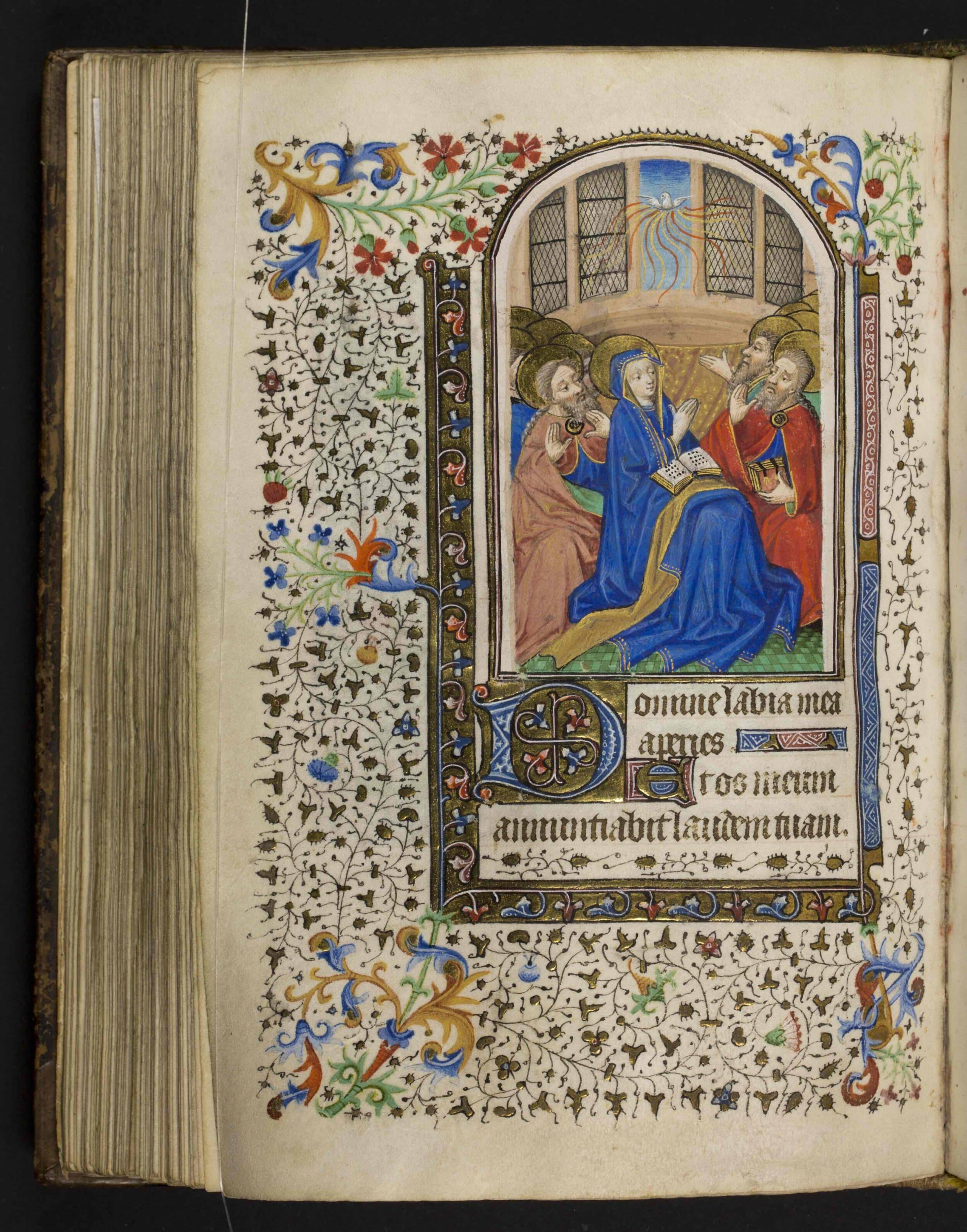

Book of Hours for the Use of Paris, illuminated by [follower of] the Master of the Bedford Hours, ca. 1435–1450

Book of Hours for the Use of Paris, illuminated by [follower of] the Master of the Bedford Hours, ca. 1435–1450© Public Library of Bruges / Van Caloen Foundation

In the Christian Middle Ages, laypeople were also expected to pray daily, although the prayer times were less strict than for religious individuals. For example, the night vigils and Lauds were often combined. The prayers during the day only took about five minutes and could easily be recited between the soup and the potatoes. Thus, the medieval prayer culture is very similar to the prayer times in Islam: (salat) times of prayer when Muslims still perform the prayer (salat) today.

Maria

Books of Hours are a late medieval phenomenon. For more than three hundred years, they were the most produced books in Europe. From the thirteenth century, when the first copies appeared, until 1571, when Pope Pius V prohibited their use during the Counter-Reformation and introduced the Catholic catechism, they could be found in almost every (well-to-do) household. In the thirteenth century, under the influence of the new mendicant orders (such as the Franciscans and the Dominicans), a broader religious interest emerged among non-religious people, especially among the nobility. For them, books were compiled with simple Hours and psalms. In the exhibition, for example, there is the psalter purchased by the Flemish government that Margaretha of Constantinople had produced – she governed the counties of Flanders and Hainaut in her own name from 1244 to 1280.

Later, the Books of Hours also gained popularity among broader segments of the population. In the fourteenth century, the disruptive impact of the Black Death (1348-1349) led to new religious movements and an increased religious community life in lay brotherhoods and sisterhoods. At the centre of this was a closer relationship between ordinary men and women and God, and with Books of Hours, the laity could pray by themselves without the help of a priest. Many hours and prayers were dedicated to the Virgin Mary, the most important mediator between God and man.

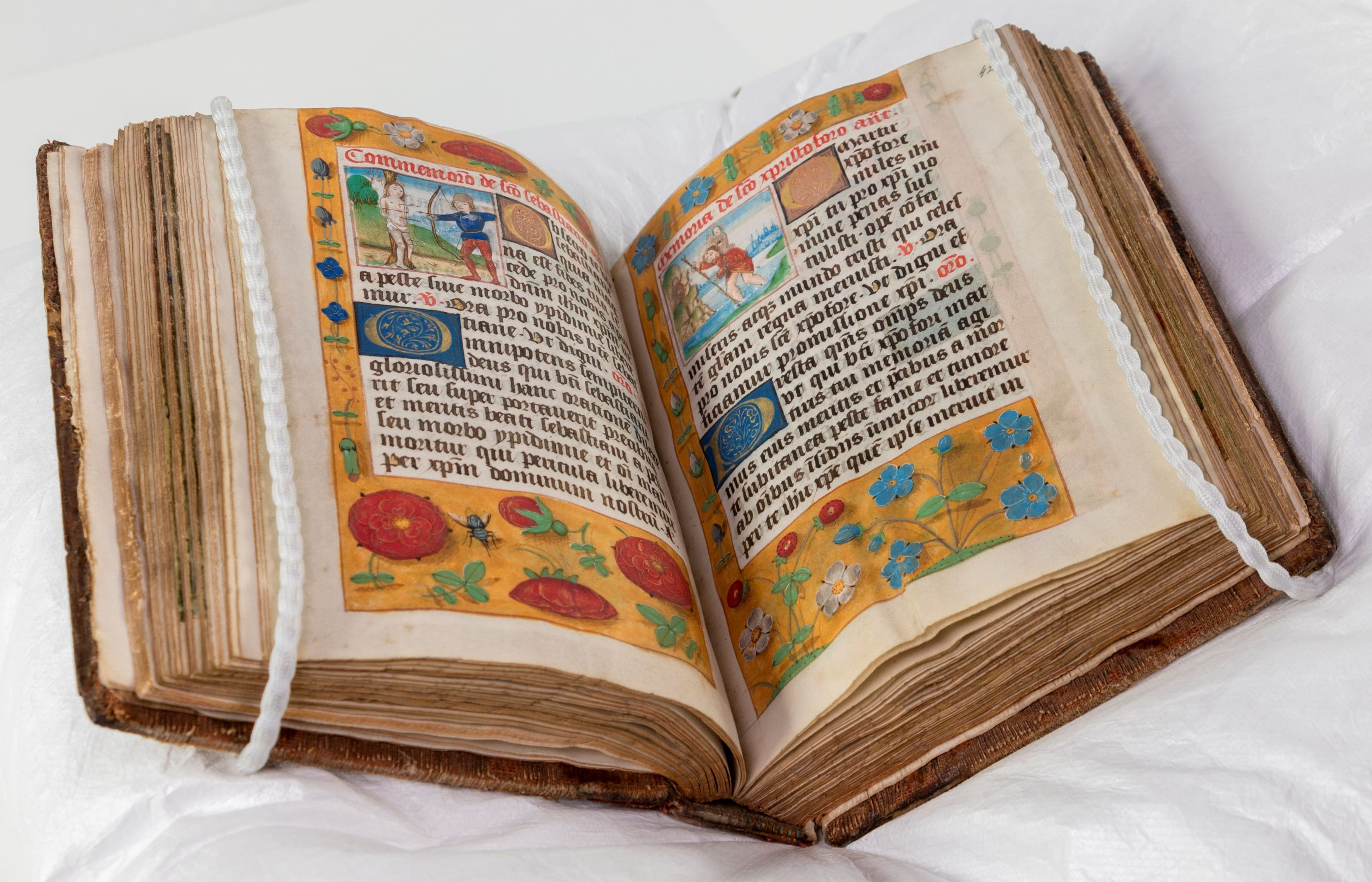

Penitential Psalms with Last Judgment, in Book of Hours, Flanders, ca. 1475 – ca. 1485

Penitential Psalms with Last Judgment, in Book of Hours, Flanders, ca. 1475 – ca. 1485© Public Library of Bruges

The psalters and Books of Hours from the thirteenth century were almost exclusively in Latin, but gradually we began to see Dutch or French translations of prayers emerging in our regions: among others by Geert Grote, a theologian and major inspiration for the Modern Devotion (a spiritual reform movement), or by Christine de Pisan, a prominent French writer from the early fifteenth century. Thus, Books of Hours are indirect witnesses to the increasing literacy of the medieval population.

They were also used in education. Several prayer books intended for children have been preserved, often containing an abecedarium, a kind of alphabet in rhyme, incorporated into them. Sometimes, between the Latin prayers, there are also aids in Dutch or French, short sections and references that make reading and browsing the Latin texts easier for a readership that was not very familiar with Latin.

Talisman

When you walk through the exhibition at the Bruges Groeningemuseum, you will occasionally need to use your back muscles to stare with your nose practically pressed against the glass: Books of Hours are small to even tiny (don’t worry, there are magnifying glasses available). The small size suggests that they were read individually rather than collectively and were often carried in a small bag or box. In the exhibition, you can admire an example of such a box with an additional secret compartment (to smuggle letters?). The prayers were read aloud, just like most books in the Middle Ages. Until the late Middle Ages, it was normal to read aloud even when alone.

Completion of the Hours of the Passion (text) and Noli me tangere (miniature), Book of Hours of Jacoba of Bavaria, Paris, ca. 1410

Completion of the Hours of the Passion (text) and Noli me tangere (miniature), Book of Hours of Jacoba of Bavaria, Paris, ca. 1410© Public Library of Bruges

Most Books of Hours are luxury items, comparable to jewellery. The most expensive copies contain beautiful decorations and miniatures. The international book market in late medieval Bruges particularly catered to the production and illumination of luxurious Books of Hours for both the international and regional markets. Standard Books of Hours were massively shipped to England to be further personalised and sold there.

Famous medieval painters such as Jan van Eyck created miniatures for Books of Hours, but usually it was specialised miniaturists, like the Utrecht-based Willem Vrelant, who established himself in Bruges and set up a workshop specialising in the illustration of Books of Hours. In that workshop, several women also worked as miniaturists.

Prayer books are often true family documents, passed down from generation to generation, and sometimes gifted at a wedding. Notably, we found that quite a few women were owners, spanning generations. Prayer books were passed down from mother to daughter, from mother-in-law to daughter-in-law, from stepmother to stepdaughter, like a precious jewel. The text in these books was not ‘fixed’ – occasionally a prayer, song, or scribble was added, such as the birth and death dates of a child. They were real talismans. The miniature of Saint Margaret, who guaranteed a swift delivery, can be found in many prayer books in worn condition: heavily pregnant women rubbed over it multiple times before going into labour.

Books of Hours may be small booklets, but you won’t find anything closer to real medieval readers. You know that the Flemish Countess Margaret of Constantinople truly held this booklet in her hands and used it daily. Books of Hours are more than just books. They are unique windows into the real lives of medieval people.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.