Love as Activism: The Art and Writing of Fleur Pierets

The work of writer and performance artist Fleur Pierets expresses a deep longing for an equal world, one in which everyone can live life to the full. The backdrop for this is one of great erudition, combined with an intense romantic relationship that was doomed to end prematurely.

Fleur Pierets is a novelist, dancer, singer, actor and director.

Fleur Pierets is a novelist, dancer, singer, actor and director.© Uitgeverij Oevers

Are you a novelist, dancer, singer, actor or director? This is undoubtedly an awkward question for Fleur Pierets (b. 1973). Although by her own account she always wanted to be a writer, she already had diverse works of art to her name before her debut on paper.

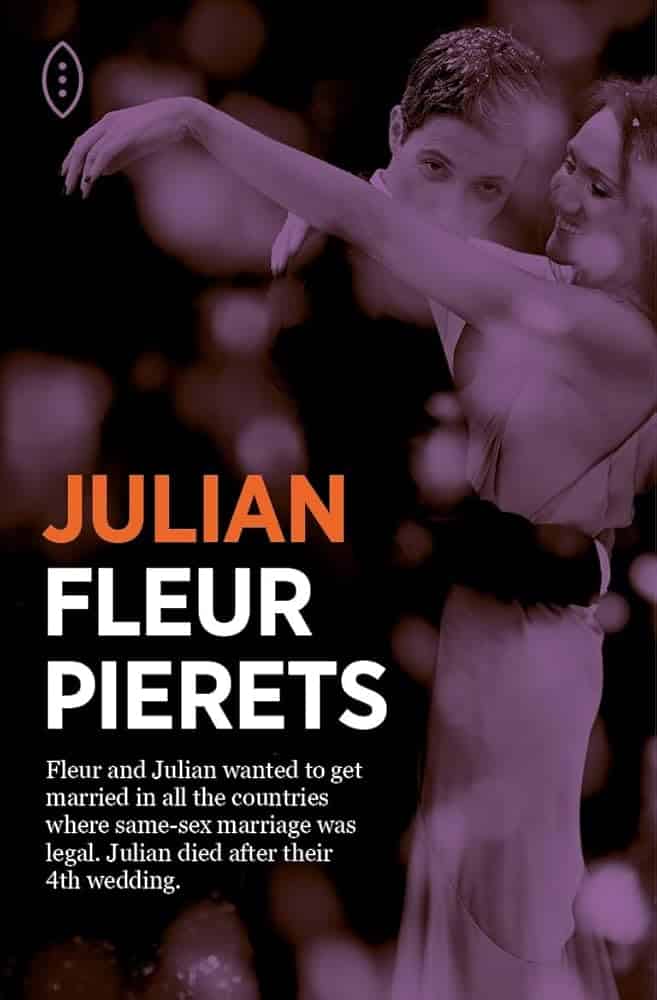

She first acquired fame, alongside her partner Julian P. Boom, with the foundation of Et Alors? Magazine, a publication dedicated to conversations with queer musicians, visual artists, writers and performers, which has produced a total of twenty editions since 2014. The couple picked up further popularity with 22, a performance art project in which the couple planned to get married in every country that permitted homosexual marriage at the time.

Fleur Pierets and her partner Julian P. Boom at one of the wedding ceremonies of the 22 project.

Fleur Pierets and her partner Julian P. Boom at one of the wedding ceremonies of the 22 project.© Fleur Pierets

For children as well as adults

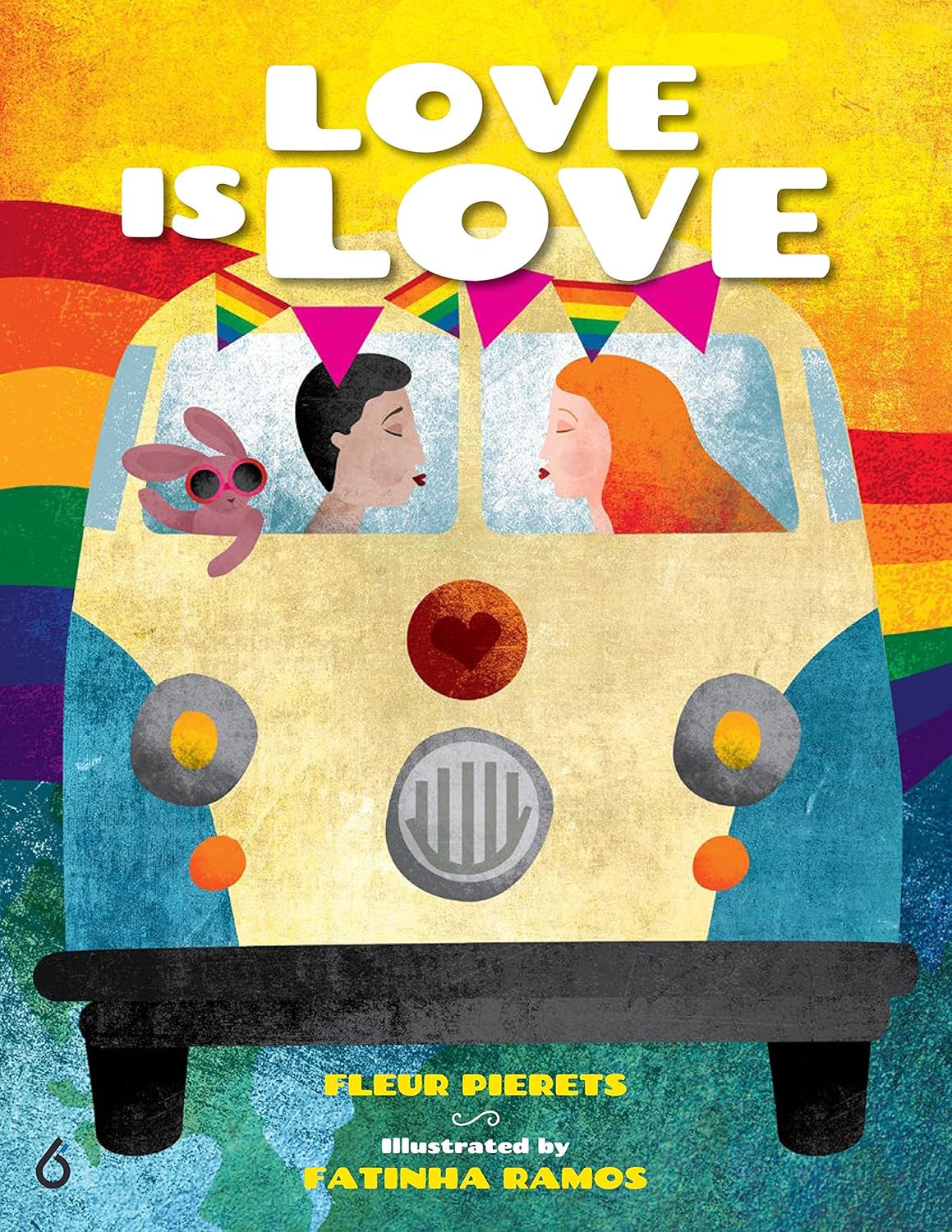

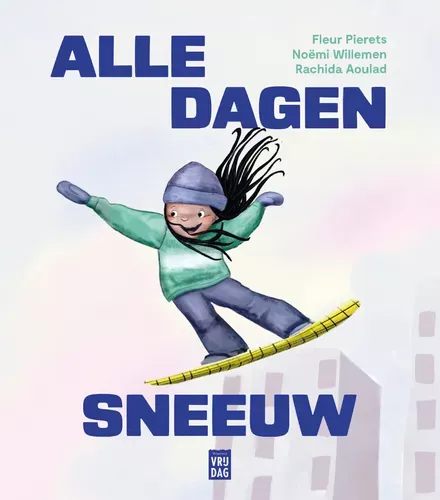

Boom, however, died after the fourth wedding, a tragedy that formed the basis for Pierets’ debut memoir Julian. This was followed in 2022 by the two-part children’s book Love around the World and Love Is Love, commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. Here she rewrote her love story for a different target audience. In collaboration with Noëmie Willemen and Rachida Aoulad she also produced the Dutch-language picture-book Alle dagen sneeuw (Snow Every Day), about a snowboarding girl investigating why she receives less applause than the boys.

The same year saw the publication of Heerlijk Monster (‘Lovely monster’), about a nameless writer roaming the United States with Patricia Highsmith’s book Carol in hand – the first novel depicting a romance between two women that ends relatively happily – in search of the places the lesbian main characters visited in their day. In 2024 Pierets added Beton (Concrete) to her body of work, an essayistic exploration of different forms of pain, loneliness and fear – emotions that were already established among her major themes.

Part of the queer community

Both Pierets’ written work and her performances focus on lesbian sexuality. After a ten-year marriage to fellow writer Jeroen Olyslaegers, Pierets drew a line under her heterosexual life and fell madly in love with Boom, a feeling she explores extensively in her debut memoir. It instantly made her part of a new circle, the queer community.

That change was one she grasped with both hands in order to reflect in word and performance on the deprived position the LGBTQ+ community still holds. In the majority of the world, as she demonstrated in 22, they are openly discriminated against and restricted, even in countries where you wouldn’t expect queer people to be harshly side-lined. Often this does not happen openly, but rather very subtly – in suspicious looks when two people of the same sex walk hand in hand down the street, with disappointed grumbling when LGBTQ+ people come out to their parents.

Illustration from Fleur Pierets’ book Love Is Love.

Illustration from Fleur Pierets’ book Love Is Love.© Fleur Pierets

Literary predecessors

It may well be down to her late entry to this community that Pierets reflects with some exploratory distance on these matters. In all her books she frequently cites other writers and researchers to back up her points. Heerlijk Monster is the clearest example of this: in this book Carol is a continually recurring subtext, revealing the subtlety with which women in 1950s America had to communicate their love for one another.

In Julian, her account of her grief, she also searches for footholds in her literary predecessors – from Oliver Sacks to Guy de Maupassant, from Tennessee Williams to Virginia Woolf. Many of the texts she quotes are about love and loss – often love that is impossible in the eyes of the world, due to a large age gap or because both partners are of the same sex.

Plea for equality

In the course of Pierets’ oeuvre such subtexts take up ever more space. For instance Beton consists almost entirely of reflections on the work of others – from the repercussions of real events to literary texts or works of art. Taking an associative route, Pierets moves from the artist Niki de Saint Phalle, famous for her sculptures of voluptuous women, to Lars von Trier’s film Melancholia and Caroline Criado Perez’s book Invisible Women, illustrating how many decisions in this world are made on the basis of the male norm – from the airbags in cars that are shaped for a male body to the choice no longer to leave street lighting on at night in large cities, making it considerably more risky for women to venture out.

The web of stories thus formed can be read as a plea for equality between the sexes and an account of years of grief. Longing for Julian indirectly permeates this book too, often in the form of reflections on the meaning of life, or the lack thereof. As in her debut, Pierets focuses on the question of what makes life worth living when something that makes us so happy can be so easily snatched away.

It is an undercurrent that is equally pervasive in Heerlijk Monster. On her journey the main character starts a relationship with Niko, a woman in her late twenties who even accompanies her for part of her travels. Although the pair clearly click, the writer keeps her lover at a distance, wary of the intimate connection that might develop between them. This might also explain the continuous references to one-night stands, which – perhaps due to the same fear – never grow into more. It raises the question of how a person’s romantic life might look when they have already lost the love of their life at a relatively young age.

Text, image, fact and fiction

Many of Pierets’ books, for adults as well as children, are a combination of text and image. In Beton the descriptions of works of art are supported here and there with pictures, and in Heerlijk Monster every chapter is introduced with a grainy snapshot indicating a location or moment in the story, such as a woman’s hand on a steering wheel or a chair in an American diner. Yet Pierets hasn’t made the journey herself, she admits in an interview with the Dutch newspaper Het Parool: she wrote the book during the coronavirus pandemic, settling for strolling around on Google Maps.

No genre label appears on the cover of Heerlijk Monster – a conscious choice, Pierets notes in the same conversation. ‘It’s not a memoir, as 80 percent of what happens in the book is not true. The first-person narrator has lost her wife and is a writer, but there the similarities end. It’s not a novel either, as the material is too personal for that.’

It’s a strong example of the extent to which fact and fiction overlap in Pierets’ work. The reading experience of Heerlijk Monster acquires significantly greater depth if we interpret the intense relationship and tragic death of Boom as lying at its heart. The same goes for Beton, where this background would explain the manic-depressive thoughts for which the narrator seeks help from a therapist. Her narrative style contributes to that overlapping of reality and imagination: it is natural, without too much embellishment, so that every sentence reads as if it could really have happened.

Plea for activism

In her ever-growing body of work Pierets focuses on a few major themes of our time: the importance of equal rights for men and women and the quest for the role love can play in our lives. Particularly on the first front, as in her performance art, she presents herself as an activist: she doesn’t shy away from giving voice to her personal opinion in her texts, and encourages her readers to take a stand themselves. For instance in Beton she writes, in response to the war the mayor of her home city has declared on everything he considers woke: ‘(…) And I consider what I’ll protest about first. Until my opinion is as important as his. Until then the question isn’t why I’m an activist, the question is why you’re not.’

Even the main character of her children’s book Alle dagen sneeuw grabs the chance to resist the prevailing norm: along with other girls from her team she takes a stand, letting the jury members of the snowboarding team know that they want the same treatment as the boys. ‘Together the friends have built a better world,’ is the concluding line of Alle dagen sneeuw – an intention that pervades every part of Pierets’ work. Both her performance art and her writing embed an aspiration for an equal world – a passion supported as much by her artistic predecessors as by her personal experience.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.