Prison Writers: Exploring the World from Behind Bars

Prison life forces reflection. Behind bars, authors confront fear, solitude, and the strict rhythms of confinement. Outside, writers try to understand that world, imagining what it is like to live with so little freedom. Together, their voices reveal the many dimensions of imprisonment.

Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote and Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis: some of the greatest works of world literature came into being in prison. It’s not surprising: detention gives people plenty of time and space to put their thoughts on paper. Often, people with innovative ideas end up locked away because their views clash with those in power at the time.

There are certain countries today where the prison literature genre is rather livelier than it is in the Dutch-speaking region. Nevertheless the Netherlands and Flanders also boast several novels narrating life behind bars. Among them the debut short story collection Galgenaas (Gallows Bait), by Flemish writer and journalist Roger Van de Velde (1925-1970), and Ik lach om niet te huilen (I Laugh to Avoid Crying), by Dutch author and sports journalist Lex Kroon, have for several decades offered insight into prison life and the path that leads there.

Writers on the inside and on the outside

The appearance of the collection Gevangenispost (Prison Post) in 2022 added a new title to this genre’s representation in the Low Countries. Ten prose writers and poets in detention – we’re only told their first names: Melvin, Job, Khalil, and so on – correspond with as many established authors in the Dutch-speaking region, including Christine Otten, Raoul de Jong and Marjolijn van Heemstra.

The book clearly distinguishes between authors inside and outside prison. This reflects the two main perspectives common in prison literature. Those telling their story from the cell focus primarily on life inside, often zooming in on the monotony and claustrophobia; those becoming acquainted with this life from the outside are primarily inclined to reflect on what freedom means to them.

Prison writers sometimes reflect on their life before incarceration and how much—or how little—they want to return to it. At the same time they seek ways of making their stay in prison as pleasant as possible in their minds. They warm themselves on the fact that they are well looked after, as in an all-inclusive hotel: their clothes are washed, food is served and they can participate in all kinds of daily activities, although between the lines the longing for freedom is clear. At the same time there is the fear of being back on the outside: as far as they are concerned the free world has betrayed them by so cruelly locking them up.

Often, people with innovative ideas end up locked away because their views clash with those in power at the time

The writers from outside the walls primarily appeal to their empathy in an attempt to better understand the prisoners. In doing so they make use of their own memories of moments in which they felt locked up or isolated: the odd night in a cell, a stay in a monastery or – on a more poetic level – the longing for summer, which always turns out a bit of a disappointment. They sometimes feel a little artificial, these attempts to approach the experience of a prisoner. They are seldom comparable with years of confinement.

For the authors locked up, the imagination freed up in the writing process serves as a manner of escape. Through the page they are able to lead alternative lives, in which they can wander the earth freely. They also use writing as a means of reflecting on the hardships they have had to endure earlier in their lives. Often their imprisonment was preceded by a complicated childhood, with absent or ill parents, poverty and violence.

Through the page prison writers are able to lead alternative lives, in which they can wander the earth freely

It gives them enough material to fill the pages, but at times the quality falls short of great literature. The stories are direct write-ups of a lonely life, lacking in variety, the poems are childish and trite. Perhaps the most successful is the closing excerpt by Job, who palpably describes his mistrust of himself: “The fear of being alone on the one hand and the fear of encountering a man too much like myself on the other.”

Murderer and man

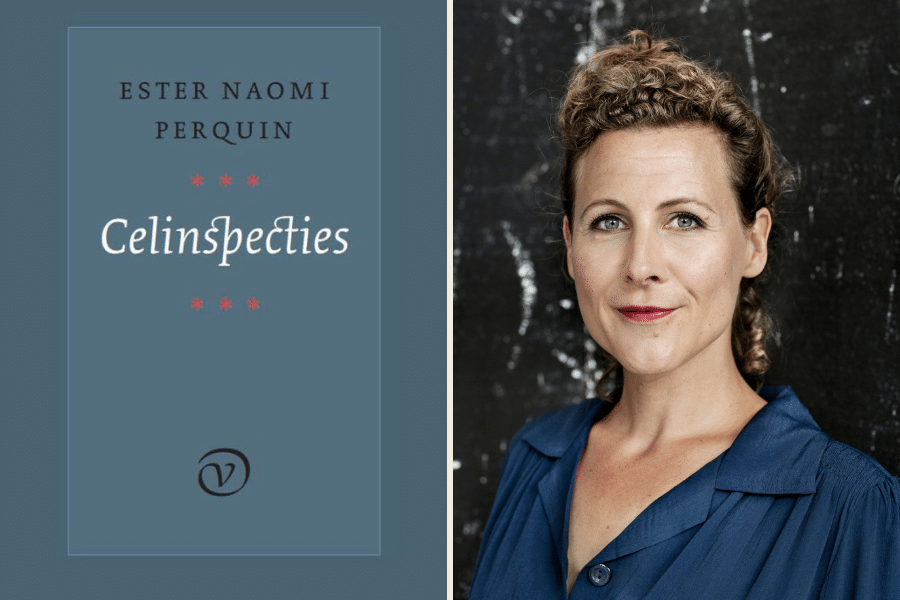

Prison life is not only captured in stories. In her poetry collection Celinspecties (Cell Inspections, 2012) Ester Naomi Perquin focuses on describing life behind bars, a life she knows from close quarters, as she worked as a prison guard to pay the bills while studying.

Nevertheless Perquin remains acutely aware of her position as an outsider. The collection opens with the lines, “Dropped me carelessly into someone else’s life that day, some else’s / driving lesson, shopping list, lecture, into someone else’s / hesitations, beginner’s legs in a dance lesson.” These lines imply that the poems will be about everyday lives. In fact nothing could be further from the truth. They are about people who have received a prison sentence. Several of the poems also bear the names of prisoners, such as ‘Frans van A.’, ‘Jakob de B’ and ‘Carlo “The Conqueror” da C.’.

The poems in Celinspecties switch between different perspectives: that of the culprit, family member or onlooker in the background. We read about feelings of regret among prisoners, about their need to defend their actions, about the lack of privacy in the cell, about the fearful nightmares which overwhelm them at night.

Ester Naomi Perquin with ‘Celinspecties’

Ester Naomi Perquin with ‘Celinspecties’ © Lenny Oosterwijk

The poetic form used by Perquin is perfectly suited to the multifaceted nature of their situations: she presents them simultaneously as murderer and as human being, as culprit and victim, as an honest person and as a hypocrite. As readers our allegiance switches back and forth, although the insight into the prisoner’s thinking helps us understand why they have ended up behind bars.

Every morning as the world opens up, you think of the girls

skipping out of the house, springing into view, their dancing

pedalling legs your dancing pedalling heart

(…)

and you think of the door, the steely smell of self-preservation, you think

of the girls, skipping into view, never knowing if

one of them jumps from her bike, runs up, loves you.

In Celinspecties it’s not only prisoners whose voice we hear. Take for example the poem ‘Frederik C.’, which reflects from an apparently neutral position on the importance of language within the setting of the court. “Take care of the whole story – don’t spare yourself too much but / shift out of the picture, take it slow,” the lyrical narrator advises, and, “Instead of murderer / you opt for ‘offender’. More room for manoeuvre, less loaded.”

Is it the verbal artist Perquin who addresses us here?

Route to prison

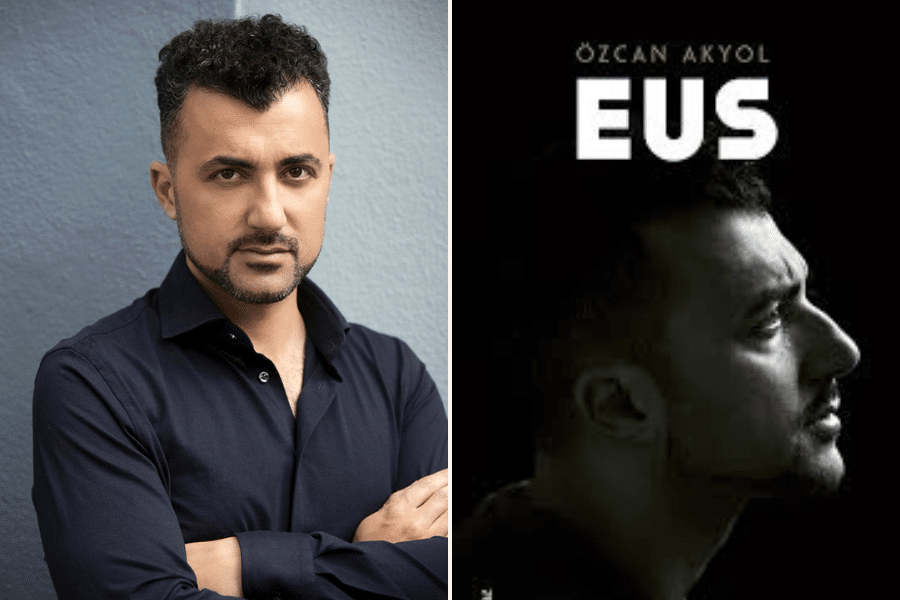

Sometimes a tale of crime can ensure a flying start in Dutch literature. Özcan Akyöl experienced this in 2012 with the publication of Eus, which was presented as a “semi-autobiographical picaresque novel”. The story – as we often see in prison literature – was to lean heavily on the personal life of the writer. His father was an alcoholic and abused his sons, leading Akyöl himself to go off the rails and end up in a remand centre and subsequently in a life of crime.

Eus sold more than 100,000 copies. Its bestseller status may be down to the near-mythical story of the boy who develops in the cell from a jailbird into a major lover and even creator of literature. The novel tells the story of a boy who doesn’t feel at home anywhere: he doesn’t fit into his Turkish family, because he rebels against their Islamic traditions, but the Dutch community doesn’t straightforwardly accept him due to his Turkish background, seemingly denying him entry to society. Despite good grades in school he is advised to opt for vocational training rather than academic study. He then becomes swept along in a vortex of excessive drinking, deception and fraud, until he ends up in prison.

Özcan Akyöl with ‘Eus’

Özcan Akyöl with ‘Eus’ © Prometheus

The novel is strongly focused on getting the reader to understand how a boy with so much potential can nevertheless end up on a path to crime. The key issue is the marginal position society has pushed him into. His personal situation also plays a role. Like the author, Eus suffers under a tyrannical father who forces him to give up his education and earn money by illegal means. Eus is surrounded by friends who push him towards the dark side of society. His unmet need for belonging pushes him towards marginal groups who only reinforce his outsider position.

The power of prison literature resides in the different perspectives that prose and poetry can offer on the themes of freedom, imprisonment and betrayal

As prison literature, Eus primarily reveals the path that has led to imprisonment. It’s a story about the deterministic aspect of society, raising the reader’s awareness of the negative spiral people can be drawn into when they start out from a disadvantaged background. When reading Akyöl’s account, we see almost no other possible route for the main character than a life of crime. Prison is the endpoint of a long road with ever deeper dips, which are made relatable for even the best behaved of good citizens.

Unlike in other countries and times, here it is rarely great philosophers who end up behind bars. Nevertheless the cell provides sufficient impetus to reflect on the meaning of freedom, imprisonment and betrayal. The power of prison literature resides in the different perspectives that prose and poetry can offer on these themes. It brings the reader new insights into the prisoner’s mind-set: what it’s like to be confronted with endless waiting, the way a stay in prison offers so much space for reflection that it can be maddening, and how the human mind uses imagination to resist that madness.

Gevangenispost. Tien schrijvers van binnen ontmoeten tien schrijvers van buiten, (Prison Post. Ten Writers on the Inside Meet Ten Writers on the Outside) De Geus, Amsterdam, 2022.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.