When British journalist Derek Blyth lived in Utrecht, it was an obscure university city, at best, a pleasant day trip from Amsterdam. Today he falls for the charms of its picturesque canals, lively pub culture, the world’s largest bike parking garage and a cute little rabbit that pops up everywhere in town.

I should have known. You can never step in the same river twice, the philosopher Heraclitus said. Things change. Of course they do. But still. It was disorienting to step off the train in Utrecht, where I had lived for nine months, and realise that nothing was the same.

When I moved there, Utrecht was an obscure Dutch city. No one I knew could place it on a map of Europe. It was seen, at best, as a pleasant day trip from Amsterdam. And yet it struck me as an interesting city. It had dark mysterious canals lined with sunken brick quays, friendly student bars and ancient stone churches. The only problem was that it was impossible to find a place to live. It still is. So I only stayed for nine months.

Citycentre of Utrecht with the Dom tower

Citycentre of Utrecht with the Dom towerA lot has changed since then. Tourists seem to know more now about Utrecht. They can even pronounce the name correctly – not you-trecht but oo-trecht. It’s beginning to get a reputation as a place to visit. More than just a day trip from Amsterdam, which is now, everyone agrees, overcrowded with tourists

Utrecht has ‘one of the liveliest terrace cultures in Europe’, according to The New York Times. It was chosen a few years ago as the liveliest Dutch city centre. And so it seemed like a good time to revisit.

The moment I stepped out of the station, I was lost. You used to arrive in the middle of a stupendously ugly shopping centre called Hoog Catharijne. Designed in 1962, it was originally seen as a bold modern plan to revitalise a dull provincial city. Located on the site of the Hoog Catharijne city gate, it was said to be the largest shopping centre in Europe. Het Winkelhart van Nederland – The Shopping Heart of the Netherlands, the developers liked to boast.

Central station of Utrecht

Central station of UtrechtThe complex combined the railway station, bus station, shops, restaurants, offices and car parks. All under one roof. It seemed a good idea at the time. Hoog Catharijne was ‘a unique, timeless urban development plan’, the planners claimed, even as they tore down an entire neighbourhood, including a striking Art Nouveau building owned by De Utrecht insurance company.

It was a disaster, according to a recent exhibition at the Centraal Museum – Dromen in Beton (Dream of concrete). The mega complex destroyed the urban fabric, increased traffic congestion and sparked off violent protests before it had even opened.

Shopping mall Hoog Catharijne and station square

Shopping mall Hoog Catharijne and station squareThe ‘timeless development’ barely lasted forty years. And now they have torn it down and started again. You step out of the bright, modern station onto a windswept plaza hemmed in by huge office buildings, a glitzy shopping arcade called The Mall and shiny modern hotels. In the distance, you might spot a giant teapot on the roof of a car park.

The most innovative element of the design lies buried below the plaza. Here the city has constructed the world’s largest bike parking garage. It’s a beautiful, bright underground complex with space for 12,500 bicycles neatly stacked, one above the other, in endless rows. But it is already too small: the city needs to add 10,000 more spaces to meet growing demand.

Bike parking garage

Bike parking garageNipping between the bicycles, I headed off in search of the Vredenburg concert centre. Built around the same time as Hoog Catherijne, this was perhaps the only successful element of the project – a warm, democratic building designed by Dutch architect Herman Hertzberger. But it took me a while to spot it. The original building is still there. But it now looks insignificant buried below four new concert halls perched on top of the original building. Renamed Tivoli Vredenburg, the cultural complex offers an ambitious programme of jazz, classical and pop music, including free concerts in the foyer. It’s definitely impressive, but I miss the intimate Dutch humanism of the old Vredenburg.

Concert hall Tivoli Vredenburg

Concert hall Tivoli VredenburgWhat else has changed? I wondered, as I crossed the empty open square in front of Vredenburg and turned down the narrow lane Drie Haringstraat. There used to be a fake English bar called King Arthur at the end of the lane with a tacky interior intended to evoke a mediaeval banqueting hall. It had gone, thank god. The suits of armour and Bass beer taps thrown away, leaving nothing except a faded mural on a side wall.

The lane emerges on the lovely canal Oude Gracht – a deep sunken canal with a lower quay reached by steep wooden steps. The canal was named Oude Gracht after the Nieuwe Gracht was dug in 1390, so it is very old (for the Netherlands), and rather strange, with dark cellars on the lower quay.

Oude Gracht

Oude GrachtThere are more than 300 of these cellars next to the canals, a unique urban phenomenon. They were built along the low brick quays to store goods shipped by river. Until recently, the dark, damp spaces were mostly abandoned. But these urban hideaways are now hot properties occupied by student bars, restaurants and even B&Bs. And they’re not cheap – a local estate agent recently listed a small cellar on sale for €325,000.

As I squeezed past old trees planted along the lower quay, I noticed strange hidden sculptures. Placed at the base of lamp-posts, these quirky works were carved by Swiss artist Jeannot Bürgi over a 20-year period. Some realistic. Others grotesque. Each one unique.

I could see the appeal of a cellar on Oude Gracht, even if it was a bit pricey. I was there on a Saturday morning, and the carillon in the Dom tower was playing a cheerful tune as flower sellers yelled out bargains. Vier bosjes voor vijf euro – four bunches for five euros.

Broodje Mario

Broodje MarioThen I remembered Broodje Mario on the Visbrug, run by a friendly Italian who sold oversized Italian buns filled with salami, cheese, chorizo and spicy red peppers. He brought an exotic touch to a time where a broodje kaas

was the default Dutch sandwich. Mario died in 2013, although his distinctive sandwiches are still sold in a shop on the Oude Gracht.

As I stood on the Visbrug, something seemed wrong. It looked as if they were constructing a tall apartment building in the city centre. Then I realised it was the beautiful Dom tower covered in a protective screen. You could see nothing of the elegant Gothic tower that has watched over Utrecht since 1382.

The Domtower before restoration

The Domtower before restorationWhen I asked at the tourist office, they told me it was going to take five years to restore. Five years! When I mentioned this to a Dutch friend, he remembered a stunt back in 1986 when a full-scale replica of a Saturn V moon rocket was built against the Dom tower. ‘People said the rocket was as tall as the Dom tower, so someone set out to prove it.’

Later in the day, I walked past a grand house with a brass sign attached to the wall. Utrecht, sy is de Parel van Euroop – ‘Utrecht, you are the pearl of Europe’, it said. Everard Meyster wrote these words in 1668 while living in his town house on Achter Sint Pieter.

Six years later, a devastating hurricane ripped through the pearl of Europe. It destroyed monasteries, tore off roofs and brought down a large part of the Cathedral. The city didn’t even bother to rebuild it. Instead, they demolished the nave, or what was left standing, leaving an empty square separating the tower from the choir. Until recently, bus number eight went straight through the Gothic arch under the Dom tower.

The Dom quarter has been settled since the Roman period when a fort was built next to the river. Nothing has survived except the fort foundations buried below the Dom square. But the outline is marked by iron strips set in the paving that are lit at night with a mysterious green light (which changes to orange on the King’s birthday).

I was following the canals as they meandered gently through the old city, past unusual shops, unexpected art and brown cafes. First the Oude Gracht, then the elegant Nieuwe Gracht, then the strangely-named Drift.

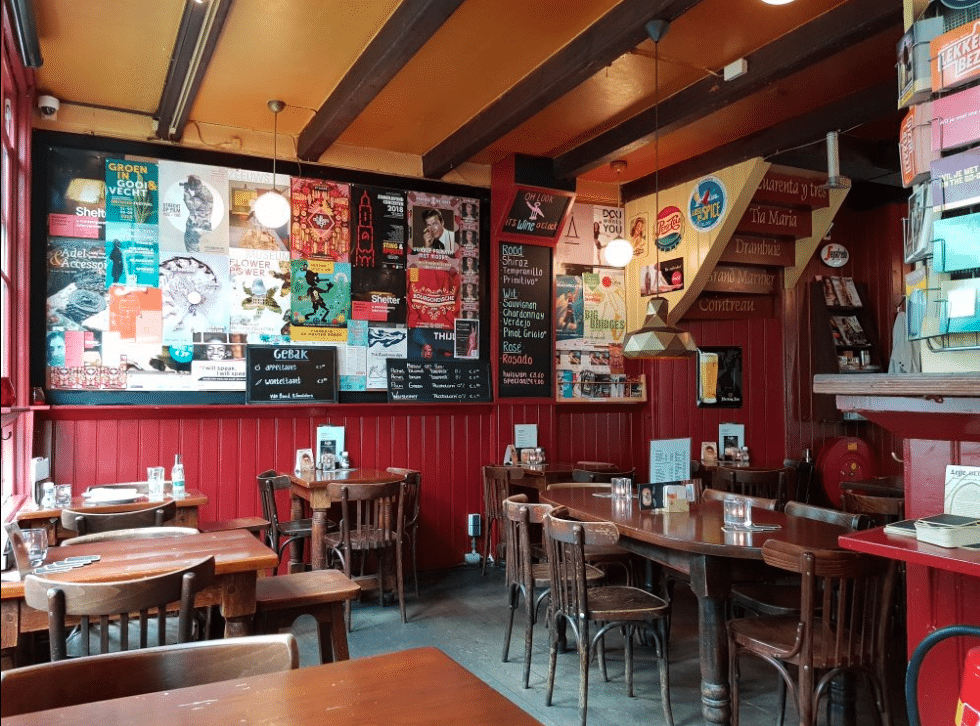

Inside café De Vingerhoed

Inside café De Vingerhoed© Thomas Haarlem

As darkness fell, I dived into the Vingerhoed on the narrow Donkere Gaard lane where the interior had barely changed since the last time I drank there. It still had its red walls plastered with theatre posters, tables at the back looking out on the canal and treacherous steps down to the toilets.

Looking out on the canal, I realised Utrecht was more mysterious than anywhere else I knew in the Netherlands. I liked the strange atmosphere along the lower canals and the narrow lanes that ran off the canals, where you might stumble upon a hidden courtyard like a Pieter de Hoogh painting, a little park with a single bench or an ancient violin workshop.

I thought I had nailed Utrecht, but I had missed something very important.

Miffy in the city

Miffy and her family

Miffy and her family© Nijntje Museum

The next morning, I went on a long walk through Utrecht. Along the way I started to notice something I hadn’t expected. The cute rabbit known as Nijntje (or Miffy in English) was popping up in all sorts of places. There was a Nijntje statue in a park. Bright Nijntje postcards next to the more traditional Rembrandt reproductions. Little Nijntjes in shop windows. It seemed Nijntje had become the unofficial symbol of Utrecht.

Dick Bruna biking in his hometown Utrecht

Dick Bruna biking in his hometown UtrechtIt eventually made sense. Dick Bruna, who created the Nijntje books, lived all his life in Utrecht. Born in 1927, he studied graphic design in Amsterdam before joining the family publishing firm. He began by designing iconic covers for Maigret thrillers before turning to children’s books. Working in a studio near the Dom Cathedral for 30 years, Bruna created simple stories about the little rabbit Nijntje using bold shapes and simple primary colours.

The city celebrates Dick Bruna the way Amsterdam commemorates Rembrandt. The Centraal Museum reconstructed Bruna’s studio in an attic room in 2015 while an enormously popular Miffy Museum opened on the opposite side of the street in 2016. You see the rabbit everywhere – on fridge magnets, pencils, school bags and balloons. There is a Nijntjepleintje (Miffy Square) with a bronze statue of the rabbit made by Bruna’s son Marc, a set of Miffy traffic lights and even a Miffy dorm in the Stayokay hostel.

Miffy traffic light

Miffy traffic lightDespite Miffy’s global success, Bruna continued to live modestly until his death in 2017. His greatest pleasure, he once said, was to cycle to his studio through the streets of Utrecht, stopping off almost every day for a coffee at his favourite local café.

The café is called Orloff. It’s a friendly place in the heart of the old town with a big old clock hanging from the ceiling and a plaque marking the window table where Bruna liked to sit. But no Miffy anywhere.

And then I discovered something surprising. It seems Dick Bruna was inspired as a small child by the Rietveld-Schröder House on the edge of Utrecht. Built by the young architect Gerrit Rietveld in 1924, this modern house at the end of a row of conventional terraced houses is still an astonishing sight. Designed for Truus Schröder after her husband died, it is a stark modern building featuring concrete walls and primary colours.

The house was almost new when Bruna was a small child. He regularly passed it when his mother took him to a local park. Its strong black lines and bold colours led to the distinctive graphic style of the Miffy books.

An Utrecht lady’s charms

I had one last place to visit. It had started to rain as I wandered down the gently curved Kromme Nieuwegracht canal looking for the house at number 3-5. A rather grim grey mansion on the edge of the canal, it was once the home of the Utrecht writer Belle van Zuylen. On a bronze plaque next to the door, a quote by Belle from 1794. ‘I don’t ask for freedom of thought,’ she said. ‘I already have it.’

The house of Belle van Zuylen on Kromme Nieuwegracht

The house of Belle van Zuylen on Kromme Nieuwegracht© Derek Blyth

Years ago, I came across Belle van Zuylen while reading the diaries of the Scottish writer James Boswell. He arrived in Utrecht in September 1763 with the plan to study Dutch law. He found a room in the hotel Het Kasteel van Antwerpen where he was immediately miserable. ‘I was shown up to an old bedroom with high furniture, where I had to sit and be fed by myself,’ he wrote to a friend. ‘At every hour the bells of the great tower played a dreary psalm tune. A deep melancholy seized upon me. I groaned with the idea of living all winter in so shocking a place. Poor Boswell! Is it come to this?’

Belle van Zuylen, painted by Guillaume de Spinny, 1759, private collection

Belle van Zuylen, painted by Guillaume de Spinny, 1759, private collection© Wikimedia Commons

Boswell’s spirits lifted in October when he met Belle van Zuylen. ‘At night you was absurdly bashful before Miss de Zuylen,’ he wrote in his diary. He even composed a love poem: ‘And yet just now a Utrecht lady’s charms/Make my gay bosom beat with love’s alarms.’

And that’s where I became interested. Sitting in the public library on the Oude Gracht with my Dutch-English dictionary, I struggled through biographies, long letters in French and Belle van Zuylen’s notorious 1762 novella Le Noble (which her father tried to ban). It was soon clear that something interesting happened in Utrecht in the winter of 1763.

James Boswell, painted by Joshua Reynolds, 1785, National Portrait Gallery, London

James Boswell, painted by Joshua Reynolds, 1785, National Portrait Gallery, London© Wikimedia Commons

Isabella van Tuyll van Serooskerken was 23 when Boswell entered her life. She came from an old aristocratic family that owned the cold grey-stone town house on Kromme Nieuwegracht along with an ancient castle on the River Vecht. The young Isabella had visited Paris and Geneva with her Swiss governess at the age of ten. She learned French in Geneva and met the painter Maurice-Quentin de la Tour in Paris. She also came in contact with new French ideas on liberty and nature, which led to her rejecting the old notions of her father’s generation.

It was clear from the beginning that Boswell and Belle were incompatible. ‘You was shocked, or rather offended, with her unlimited vivacity,’ Boswell wrote in a diary entry dated 28 November, after they played cards together. By the following January he was criticising her boundless vanity, and by April he had definitely scored her off his list of potential wives. ‘Zélide was nervous. You saw she would make a sad wife and propagate wretches,’ he wrote. ‘She would never make wife,’ he told himself three weeks later. ‘You would be miserable with her,’ he reminded himself on 11 June.

Boswell left Utrecht in the summer of 1764. He never saw Belle again. Heraclitus was right. You cannot step in the same river twice.