When Flemish Rabbits Fed the Poor of London

When people think about Ostend and food, it tends to be shrimps or mussels. But for Londoners in 19th century, it would have been rabbits. From the 1840s on, vast numbers of rabbits – skinned and packed into crates – were sent across the Channel by steamer to be sold in London’s markets. These “Ostend rabbits” became a popular source of cheap meat for the poor of London, and later in the century a staple in middle-class kitchens.

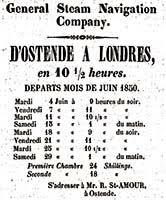

Steamers began to make regular journeys between Ostend and London in the 1820s, carrying passengers and cargo in both directions. It is not clear when rabbits became part of this cross-Channel trade from Flanders, which also included eggs and butter, but by 1843 it was large enough to attract the attention of the humorous periodical Punch. “Since the importation to this country of a vast number of Ostend Rabbits, without their furs, there is scarcely a cat to be met with in the Netherlands,” it quipped. “A correspondent has suggested, that they should in future be called Ostensible Rabbits!”

Market stall in Hoxton Street, Shoreditch

Market stall in Hoxton Street, ShoreditchⒸ Bishopsgate Institute

The appearance of skinned rabbits on London market stalls would indeed have been rather odd. People were used to buying wild rabbits with their fur on, from game dealers, grocers, or even ‘rabbit men’ who walked the streets with the animals dangling from a pole. According to one contemporary game dealer, skinned rabbits would hardly have been saleable in the late 1830s.

But Londoners knew a good thing when they saw it, and these skinned rabbits were cheap, plentiful and generally wholesome. The carcasses may have looked odd with their fur off, but the meat appeared appetising. This was partly because Flemish rabbits tended to be bigger than wild English rabbits, partly because the muscles plumped out when pressed into boxes.

Piles of these cases, each containing about 120 rabbits, would arrive in London every Wednesday and Saturday, courtesy of The General Steam Navigation Company. By 1852, London was importing 50-100 tons of rabbit meat every week, providing work for some 1000 salesmen, porters and other workmen, and feeding approximately 100.000 people.

While the cross-Channel steamers made the Ostend rabbit trade possible, there was no time to waste if the carcases were to remain saleable for more than a day or so. Traders would gather at the wharf where the steamers docked at break of day, hoping to be first in line to claim their produce.

“There would be jostling and pushing for position,” wrote Ambrose Keevil, in his history of the Fitch Lovell food company. “Tempers were often short at that hour in the morning. The one thing they all dreaded was fog, which meant the boats would be delayed. There was no refrigeration then, and the highly perishable rabbits would have to be quickly sold off to costermongers either on the spot or back at Smithfield [market]. At the best of times the vans would be loaded as fast as possible and the teams of horses would gallop away at full speed to try and get to the shops first.”

A bird's eye view of Smithfield Market, early 19th century

A bird's eye view of Smithfield Market, early 19th centuryⒸ The Met Museum

Costermongers sold from barrows, buying produce from the main food markets and taking it out into the poorer districts of the capital. In his 1851 book London Labour and the London Poor, Henry Mayhew observed that rabbits were a popular item, with some costermongers selling little else for five or six months of the year. A survey of Whitecross Street market on a Saturday in November 1862 found nine stalls selling Ostend rabbits, all undercutting the near-by shops and doing brisk business. “They were a perfectly fresh and wholesome article of food,” James Greenwood reported to a committee of the Royal Society of Arts, adding that “poor people believe in the barrow man.”

Just how these Ostend rabbits were cooked in the poorer households is hard to determine, although boiling or stewing seem the most likely. As the 19th century progressed, recipes for cooking Ostend rabbit began to appear in women’s magazines and books of household management, indicating that any stigma attached to rabbit as poor food soon passed. For an adventurous cook, there were lots of possibilities, with no less than 124 recipes appearing in Georgiana Hill’s 1859 book A Gourmet’s Guide to Rabbit Cooking, from soups and pies to roasts and curries. Meanwhile, grocers started to advertise their ability to deliver Ostend rabbits as needed.

The fact that Ostend rabbits could be shipped across the Channel in such numbers and still turn a profit for all concerned was a mystery to many British observers. It was often assumed that the rabbits were reared in vast warrens, or culled from the abundant wild rabbits living in the sandy soil around Ostend. But when journalists visited Flanders in 1882 to investigate, with a view to England copying this early form of factory farming, they found a more prosaic answer.

The fact that Ostend rabbits could be shipped across the Channel in such numbers and still turn a profit for all concerned was a mystery to many British observers

Almost all the Ostend rabbits were reared in back gardens and on farms, where they were generally looked after by the children in the household. This activity was both the children’s contribution to the family income, and an introduction to livestock rearing. The rabbits were fed on kitchen scraps and greens gathered from the hedgerows, so both in terms of labour and food they cost next to nothing to keep.

The rabbits were collected alive by small traders who travelled from village to village, and delivered to depots in the larger towns – one Belgian report of 1873 gives the main centres as Torhout, Staden, Tielt, Ruiselede, Eeklo and Ghent. Here the rabbits would be killed, skinned and boxed, before being handed over to the steamship company in Ostend. The skins were just as valuable as the meat, if not more so, with rabbit fur sold on for trimming coats, making muffs, hats and so on. Ingenious methods were developed for trimming and dying rabbit fur so that it could pass as seal, for example, and this too gave rise to a vigorous export trade.

National Utility Rabbit Association

The trade in Ostend rabbits remained strong throughout the century, until challenged by imports from even further afield. Australia was experiencing an epidemic of wild rabbits, and thanks to the arrival of refrigerated shipping could now think of exporting rabbit meat to Europe. Cheaper than rabbit from Flanders, it started to make its presence felt from the mid-1890s onwards. By this time, Ostend rabbit might refer to any rabbit sold skinned, regardless of where it came from.

The final blow to the cross-Channel trade came with the First World War, when Britain was forced to take domestic rabbit breeding seriously in order to fill gaps in its meat supply. A National Utility Rabbit Association was set up to encourage home rabbit breeding and give advice on feeding, diseases and the formation of rabbit clubs. One of its first challenges was apparently to convince the British public that home-produced rabbits did not taste “hutchy”, but were in fact the same as Ostend rabbits.