‘Schervenstad’ by Hanan Faour: Torn Between Peanut Butter and Molokhia

In Schervenstad (Shard City) Hanan Faour has written a moving story about what it is like to discover the land of her father and brother.

It is unclear exactly what the young Dutch-Lebanese Nadine had expected from her arrival at the airport in Beirut, but things are less cordial than she hoped. She can only hope the customs officer had muttered something along the lines of “welcome home.” Her knowledge of Arabic is insufficient to sustain a conversation.

And the reunion after more than ten years with her twin brother Isaac is also very awkward. Fortunately, he plays a cassette with an old song by Marco Borsato and Ali B in his dilapidated Mercedes, otherwise, she might as well have driven into town with a complete stranger. Her brother is not a stranger, Nadine thinks, but he has become unrecognisable.

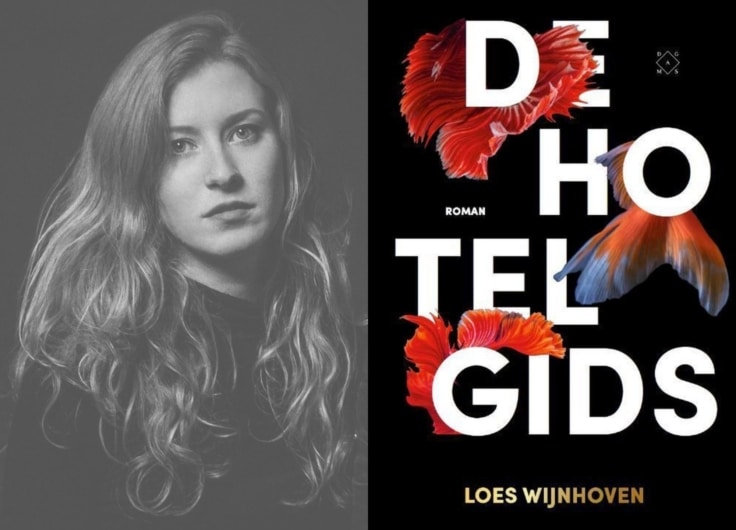

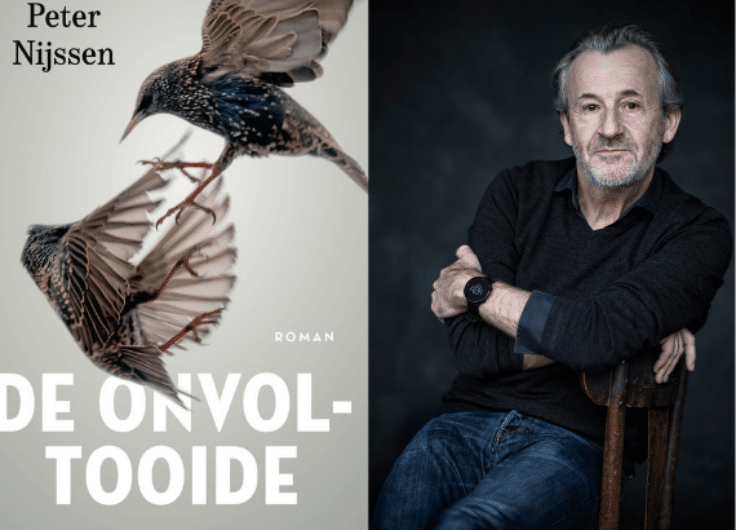

Hanan Faour

Hanan Faour© Anneke Hymmen

Twins Isaac and Nadine were separated at fourteen when the marriage of their Lebanese father and Dutch mother floundered. Their father, who had fled the Lebanese civil war, now thought it was time to return to his homeland. And Isaac went with him. Nadine stays behind in Limburg with her somewhat floaty mother, “I was not important enough to stay for.”

Nadine survives by fantasizing about other lives and other worlds. “In one of the worlds, my mother was the one who left, for India. That scenario arose when she enrolled in a yoga course at the local community centre.” Every now and then, there is a touch of humour in the book.

Nadine decides to go back to Beirut after more than ten years, after the disturbing reports from Isaac about the powerful explosion in the port of Beirut in the summer of 2020. The urge to see her brother, to go back to the country where she spent her summer holidays as a child is stronger than her fear of what she will find there.

A grain silo in Beirut port, before and after the explosion in August 2020. The disaster killed 218 people © Wikipedia

But much more than the material damage in a city full of shards and the smell of petrol, it is the people who are scarred. Nadine slowly gets to know her brother in a different way, as a young man who wants to fight for the future of Lebanon. Isaac takes Nadine to anti-government demonstrations, but she doesn’t even understand the slogan written on her cheeks, she doesn’t feel at home in the protesting crowd. She would rather buy jewellery in a shop that reminds her of her childhood.

Without getting too psychological or philosophical, Faour describes how Nadine slowly but surely settles in, how she gains some understanding for her brother, how she slowly gets to know him again. Although she still agrees with his girlfriend Louise, who calls him “the biggest idiot she has ever met”, because he has the option to leave, but does not want to. But for Isaac, it is like back then in the Netherlands: wanting to leave and not being able to stay are two different things.

Together with Isaac, Nadine gets to know her family and friends again. Contact with their father is difficult, as she ultimately still feels abandoned. But her grandparents are endearing, and cooking together brings warmth. She helps with the preparation of the molokhia leaves. Requirements: two pans, a colander, a mortar, a family.

'Schervenstad' is also a story of discovery – of a country, a culture, a mindset

And yet, those parties, which often attract half a village, are uncomfortable for Nadine too. She doesn’t understand the language, and sees people looking at Isaac and her strangely. “As if he is the blueprint, and I am the experimental version that is not quite right.”

Schervenstad (Shard City) is the story of a reunion with a father who once abandoned his daughter, the reunion of twins who in more innocent times were inseparable and swore they were. But it is also a story of discovery – of a country, a culture, a mindset.

Faour knows how to neatly interweave those two voyages of discovery, and does so in often moving beautiful scenes, without becoming sentimental. She has an eye for telling details, such as when Nadine puts fruit instead of chocolate sprinkles in Isaac’s suitcase before he leaves for the last time. And her metaphors are often poetic, describing their grandmother as being made of crepe paper. “Everything here is so fragile that it is transparent and could rupture at any moment.”

Without moralising, Faour illustrates that there are always reasons to stay somewhere, but also reasons to leave (again). Nadine left for Lebanon with the motivation to help her brother, her family, and the people there to clear the rubble. But she eventually wonders how credible that is. Perhaps it is equally important to process the debris caused by the divorce, and that’s what she’s doing there. Or maybe she doesn’t have to choose? Perhaps choosing between your country and yourself is not really needed at all?

Excerpt of ‘Schervenstad’, as translated by Elisabeth Salverda

After Isaac left, everything changed. We became magnetically charged, both positive or both negative, and it felt like everything in the world, every branch, stone and drop of water, started to vibrate when we got too close.

All possible encounters were unconsciously prevented: Isaac booked holidays to the Netherlands when I was at festivals abroad, I did not tell him about my trip to Nicosia and a week later he posted photos of him and his friends at a wedding in the Greek part of Cyprus. When Isaac made a surprise visit to mum at Christmas two years ago, I was in London with Roos, Lena and Ines. Three days later on our return journey, a train delay meant I didn’t get home until eleven at night, when Isaac had just left to visit a friend in Dusseldorf.

If I dwell on the moments that we’ve deprived ourselves, and each other, without realising, I feel sick. I don’t know if we can still catch up on everything we’ve missed:

all our own birthdays, and those of our parents and grandparents, the 18, 50, and 75 flags we hang by the front door,

shared nerves for our final exam where we accidentally meet in the kitchen at 3 am, sharing a box of cereal while trying to memorise the most important parts of our history textbook,

trips to Ikea when leaving home, and having to rent a van because the mattresses do not fit in the car,

getting our driver’s licenses, me first and him half a year later, how we argue about who gets to take the car on Friday night, our first time through the McDrive,

each other’s first real loves and first real heartaches,

all the inside jokes that could have arisen during dinner, car rides, train rides, holidays, and Sunday morning breakfasts,

the 11 years, more than four thousand days, almost six million minutes apart

Is he still my brother, or a stranger with whom I shared a womb? What does our genetic makeup mean if I can’t remember what his voice sounds like without the filter of electronics, whether he’s a morning or evening person, what drinks he orders in restaurants and how purple the circles under his eyes are when he’s stayed up all night? I see my bike mechanic more than I call Isaac.

Hanan Faour, Schervenstad, De Geus, 2022, 200 pages