Helen Simpson’s Choice: Willem Elsschot and Stijn Streuvels

Every month, a translator of Dutch into English gives literary tips by answering two questions: which translated book by a Flemish or Dutch author should everyone read? And, which book deserves an English translation? Helen Simpson makes a case for revisiting Willem Elsschot’s timeless satire Cheese, and for rescuing from obscurity a stark, snow-lit Christmas tale by Stijn Streuvels that awaits its first English incarnation.

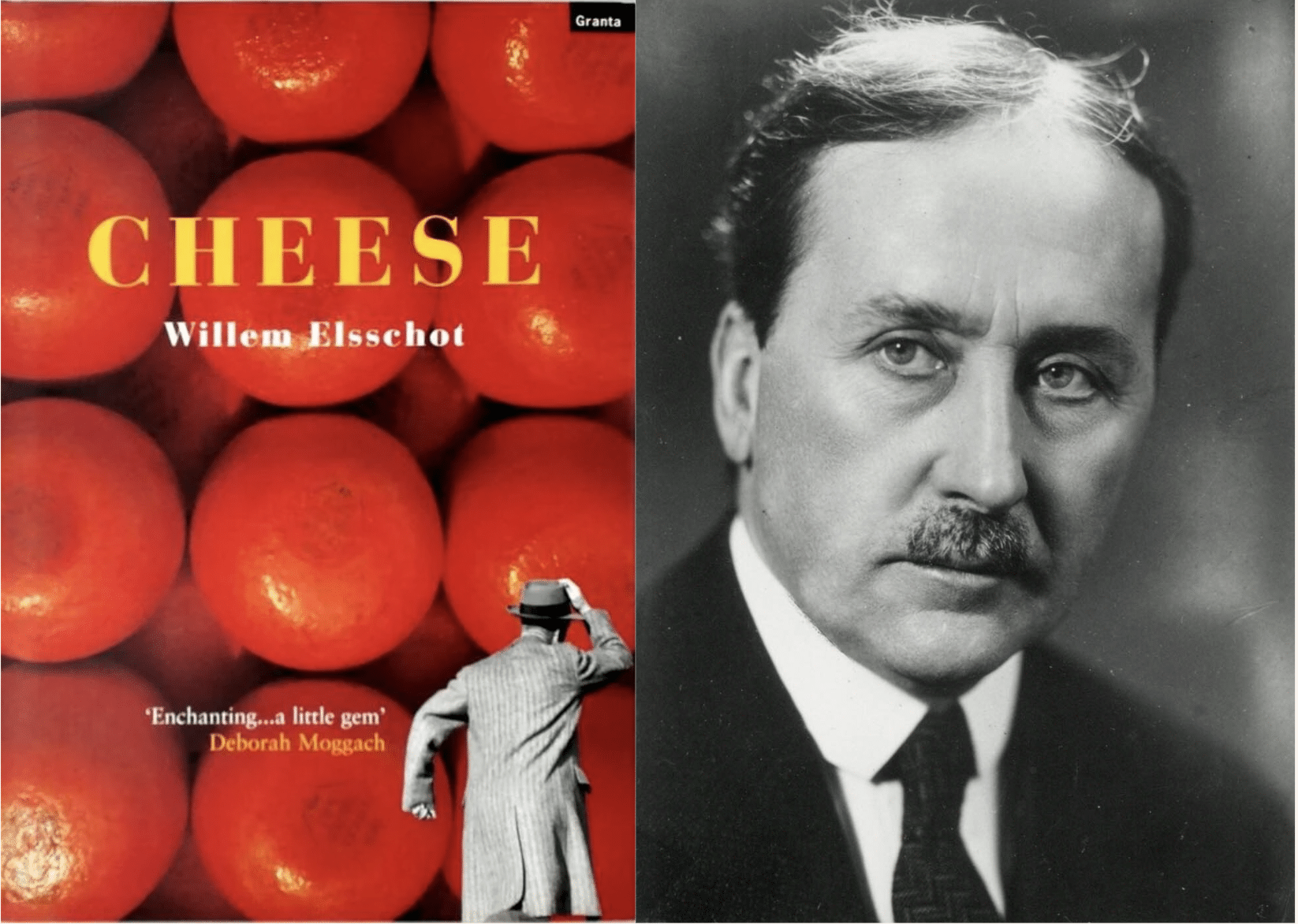

Must-read: ‘Cheese’ by Willem Elsschot

Willem Elsschot

Willem Elsschot© Collection Letterenhuis, Antwerp

I’ve chosen Cheese (1933) by Willem Elsschot (1882-1960), often described as “the most translated Flemish novel of all time”. Yet despite its immense popularity, Cheese didn’t exist in English until Paul Vincent’s translation appeared in 2002, a full sixty-nine years after its original publication. My Belgian husband gave me the book in 2004, the year I moved to Ostend, as a quirky and delightful introduction to Flemish literature (I had yet to learn Dutch). I’ve read it several times since and love it more and more each time.

It recounts an episode in the life of Frans Laarmans, a clerk at the General Marine and Shipbuilding Company in Antwerp. He is a married office worker with two children: so far, so predictable. Until one day, his wealthy friend, Mr Van Schoonbeke, encourages him to go into business. The latter puts him in touch with Mr Hornstra in Amsterdam, a manufacturer of full-fat Edam cheese, who is seeking an exclusive wholesaler for Belgium and the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Cautious by nature, Laarmans is reluctant to resign from his job until he is certain that the enterprise will succeed. With the help of his doctor brother, he takes a period of sick leave, citing “nerves”.

As Laarmans throws himself headlong into his new profession, we follow this almost absurdist tale with a mixture of wonder (at his optimism, enthusiasm and courage) and also trepidation (at his naïveté and inexperience). Cheese is a light, funny novella and a genuine page-turner. Yet on a more serious note, it also explores a universally recognizable theme: the dilemma of leaving a secure job for a risky venture, and the tension between financial stability and personal fulfilment. Elsschot paints a captivating portrait of a man striving to better his lot, while vividly evoking family life and the perils and pitfalls of trade and commerce.

Willem Elsschot, Cheese, translated by Paul Vincent, Granta Books, 2002, 134 pages

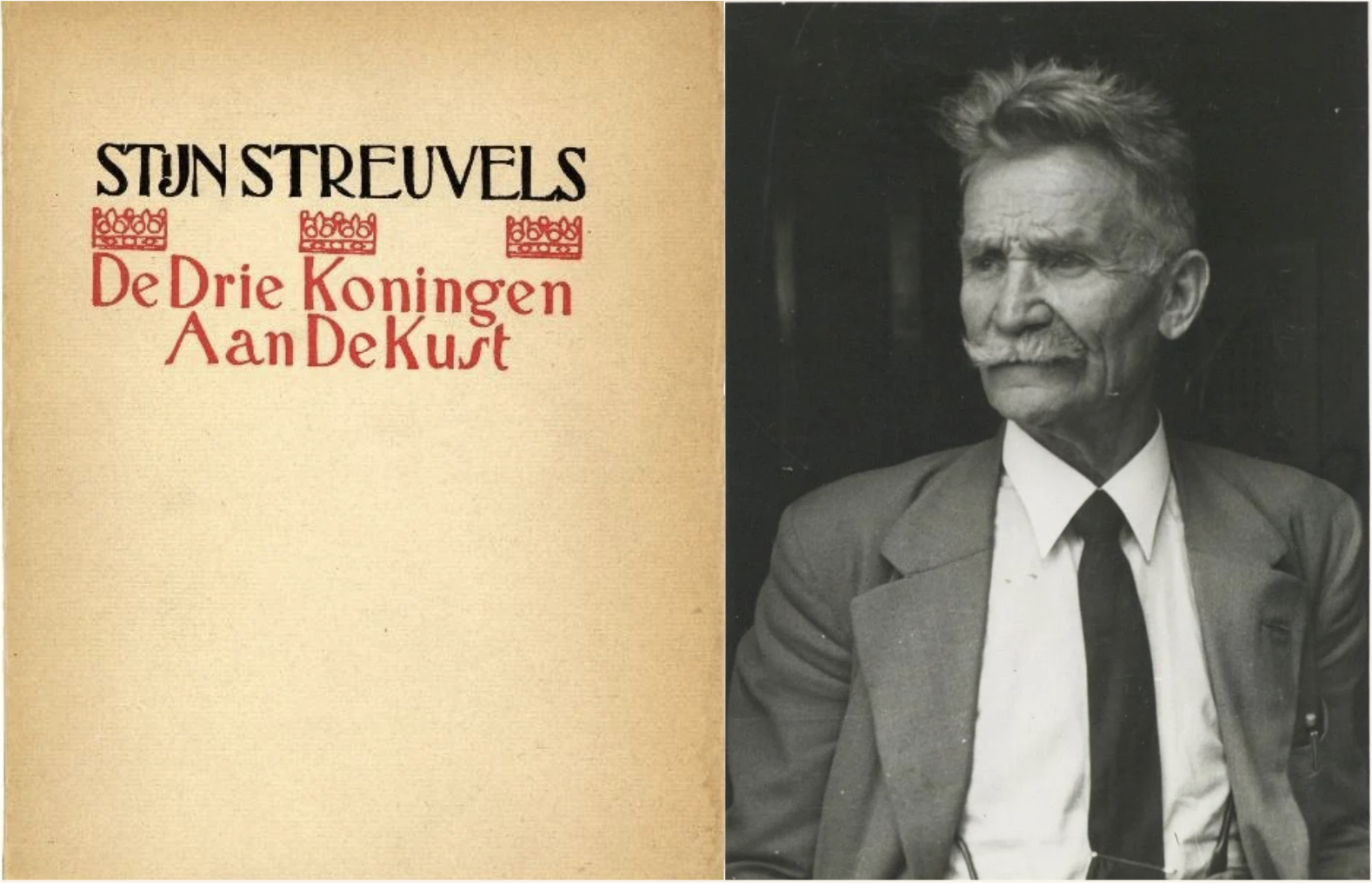

To be translated: ‘De drie koningen aan de kust’ by Stijn Streuvels

Stijn Streuvels

Stijn Streuvels© Collection Letterenhuis, Antwerp

I’d love to see De drie koningen aan de kust (The Three Kings at the Coast, 1927) by Stijn Streuvels (1871-1969) translated into English. It’s a strange and beguiling tale about three outcast fishermen – Pinkel, Viane and Karkole – who face spending Christmas Day alone. Karkole has a premonition and persuades his friends to set off on a journey inland, in search of the wondrous Christmas star.

The fishermen turn their backs on their familiar world – the sea and their boat – and head into the countryside, where they are like fish out of water. The land proves hostile and merciless. Caught in a blizzard, the trio lose their bearings and are haunted by the spectre of the Roesshard.

Streuvels writes lyrically about the coast, the water and the sea in this book, making it an intriguing counterpoint to his depictions of rural Flanders. Yet when he does turn to the landscape in De drie koningen, it is not one we recognize: this is a blank, white terrain, devoid of colour and landmarks. My dream is to translate The Three Kings into English and produce a facsimile edition, complete with the original illustrations by Jules Fonteyne.

Stijn Streuvels, De drie koningen aan de kust, L. Opdebeek, 1927, 54 pages

Excerpt from ‘De drie koningen aan de kust’, translated by Helen Simpson

DYKE AND DUNES lay beneath a thick layer of snow – white stretched as far as the eye could travel. The fishing village was enveloped, as though under a blanket on which darkness seemed to have no hold. § Pinkel, socks in trouser legs, on heavy clogs, and Viane and Karkole, in high waders, walked abreast without looking back, like men on a mission, heading straight for their goal. Swinging from their shoulders in a string bag was their meagre share of the leftover catch. § The whole village centre, and all around the houses they passed, exhaled the smell of frying fat, hot cakes and waffles – the tantalizing aroma seemed to rise from every chimney of the low houses. It stirred them not. They hurried on – eager to escape notice, shunning all contact, intent on leaving every acquaintance far behind – and headed inland. The thrill of adventure gripped all three; the lure of their obscure imaginings spurred them on. When they reached the midst of a vast flatland – nothing in sight, not a single house or stake or living creature, only a barren, snow-covered landscape with its black horizon – their curiosity about the great unknown began to stir. Henceforth, all their encounters would be fortuitous; here lay the realm of wonders that Karkole had talked into his companions’ heads. § They walked for a long, long time, exchanging the scant knowledge they had gleaned from their country encounters and experiences; their urgency and elation abated, and they began to look forward to the first event. One pictured a chance to rest, see folk and eat a warm waffle; the other: to sit beside a roaring fire, play cards and enjoy a stiff drink. But Karkole anticipated something that he could neither define nor express – something mysterious, related to Christmas Day. His premonition told him that he would witness the miracle – what it might be or become, he could only guess, but it would be profoundly moving – and the thought filled him with longing. § They trudged onwards – shabby wretches – enraptured by an illusion, their hearts courageous and their spirits elated, seeking the happiness they had persuaded one another was real, and which they were convinced they would find, across the snowy landscape where there seemed little chance of encountering anything at all. If only a dwelling, or a light might appear! Pinkel had never dreamed such a vastness lay beyond the open sea: such endlessness, without stakes or bushes, without verges or furrows, without any living creature… and nowhere an inn! He felt unsteady on firm ground, accustomed as his step was to the swell of the sea – and he’d never walked so far in a single stretch; he cursed the snow that clung to his clogs with each stride, making him teeter above the ground as if on stilts, until a clump dropped off, whereupon, tottering on one leg, he stumbled forth. He was exhausted. §

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.