‘Stinkkatten’ and Turkey Parties: How Migration Shaped Dutch in America

Flemings who emigrated to North America in the 19th and 20th centuries cherished their Dutch, while combining it creatively with English. This gave rise to a unique way of speaking, showing what life was like between two worlds, a mix where drijvers (drivers) had to be careful of stinkkatten (skunks) in the left trafieklaan (traffic lane).

Migration is timeless. Just as people today travel the world in search of better opportunities, it was no different roughly two hundred years ago. Between 1830 and 1930, thirty to sixty million Europeans left their native countries to try their luck in North America, particularly in the United States and Canada.

During this period, Europe suffered from crop failures and widespread famine, and the Industrial Revolution fuelled even greater poverty. Across the Atlantic, things seemed far more promising. North America beckoned with abundant farmland, better working conditions, and higher wages. It is hardly surprising that many chose to make the move.

Chasing their luck in America, approximately 150,000 Flemings crossed the Atlantic

Among those chasing their luck were Flemings as well: approximately 150,000 of them crossed the Atlantic. Most began their adventure at the docks in Antwerp, where they boarded a ship from the Red Star Line bound for New York. Upon arrival, they continued their journey to the Great Lakes region, including Michigan, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Indiana.

Most migrants began their adventure at the docks in Antwerp, where they boarded a ship from the Red Star Line bound for New York

Most migrants began their adventure at the docks in Antwerp, where they boarded a ship from the Red Star Line bound for New York © Wikimedia Commons

Many migrants followed relatives or neighbors who had crossed the Atlantic before them. These networks helped them find employment and integrate with others from their home country. For example, we know that a large group of Flemings worked at the John Deere factory in Moline (Illinois), while others earned their living at the Ford Motor Company in Detroit (Michigan).

A suitcase full of language

The Flemings took more than just suitcases of hope and dreams when they emigrated. They brought their Dutch language with them as well. Their mother tongue found itself in an entirely new world, one dominated by English. Yet Belgian Dutch did not disappear. In fact, many migrants kept speaking their native language at home and within their communities, though their language now bore clear marks of their new environment. They mixed English words with Flemish twists or coined new terms for typically American phenomena. Thanksgiving, for example, was referred to as a turkey party, while skunks were called stinkkatten (literally stinking cats).

This vibrant, hybrid language can be seen in the letters and postcards emigrants sent back to friends and family in Belgium, as well as in the newspapers they founded and published in the United States and Canada.

Many migrants kept speaking their native language, though their language now bore clear marks of their new environment

Nevertheless, little attention has been paid to the linguistic aspect of this heritage. My doctoral research seeks to address this by exploring how early Flemish Americans navigated language in their new homeland.

Flemish farmers in Wallaceburg (Ontario, Canada) in 1929

Flemish farmers in Wallaceburg (Ontario, Canada) in 1929 © Louis Varlez Family Archive

My objective is not only to document the interplay between languages, but also to tell the story of a community that balanced preservation and change, using language to define its identity between two worlds.

Here, Dutch (and English) is spoken

In my first study, I examined Flemish migrants’ attitudes toward both English and Dutch. How important was learning and speaking English? Were the Flemings committed to preserving their mother tongue? What roles did the two languages play in the lives of these migrants?

In order to answer these questions, I read three Flemish-American newspapers thoroughly: De Volksstem (1890-1919), the Gazette of Moline (1907-1940), and the Gazette of Detroit (1914-2018). After all, newspapers provide insight into a language community, as seen in today’s articles about the role of English in higher education, the preservation of the “dt” rule, and whether it should be groter dan (“greater than”) or groter als (“greater as”).

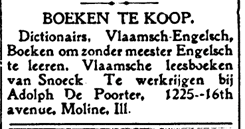

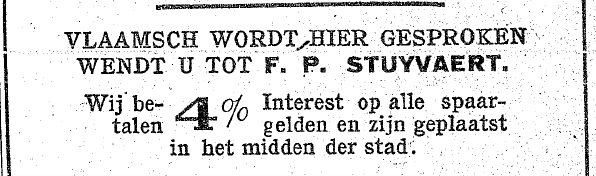

Advertisements such as this one, published in De Gazette of Moline (1910) and De Volksstem (1911), commonly included the phrase ‘Hier spreekt men Vlaamsch’

Advertisements such as this one, published in De Gazette of Moline (1910) and De Volksstem (1911), commonly included the phrase ‘Hier spreekt men Vlaamsch’© De Gazette van Moline / De Volksstem

Examining the three newspapers in depth offered a rich, detailed portrait of the Flemish-American community. It was immediately evident that preserving their native language was a priority for the Flemings. Numerous articles emphasised how important it was to speak and use Dutch, not only at home but in public as well. Bank and store advertisements often included the phrase “Here, Flemish is spoken,” and announcements of Dutch-language plays, concerts, and books were a common occurrence in all the newspapers. Editors also made frequent appeals to the pride and emotions of their readers to keep the language alive. A 1907 issue of the Gazette of Detroit proclaimed: “The Fleming who does not know or honour his mother tongue is a mutilated Fleming, but he is not yet an English-American!” It was clear that Belgian Dutch had to be preserved.

That said, this did not mean there was no space for English. I discovered multiple notices from Flemings eager to help others from their home country learn the language of their new homeland. Each newspaper advertised English lessons, English-Dutch dictionaries, and English magazines.

Note’s Band, the Flemish-American music association of Moline in 1918. Many Flemish immigrants worked at the John Deere tractor factory

Note’s Band, the Flemish-American music association of Moline in 1918. Many Flemish immigrants worked at the John Deere tractor factory © Center for Belgian Culture, Moline

The Gazette of Moline went one step further: between 1910 and 1923, it provided its readers language lessons directly printed in the paper itself. English proficiency was seen as essential for integration, a key to social and economic success in America. As the Gazette of Detroit stated in 1948: “The English language is the language of our adopted homeland.”

From Dankdag to Thanksgiving

These findings led to a new question: was this welcoming attitude toward English also reflected in their language use? This served as the starting point for my second study, in which I explored how many and which English words had found their way into Belgian Dutch in America. To do this, I analysed both the newspapers and more than three hundred personal letters and postcards that Flemings sent to friends and family in Belgium. The combination of public and private voices provided a unique insight into how Dutch evolved under the influence of English.

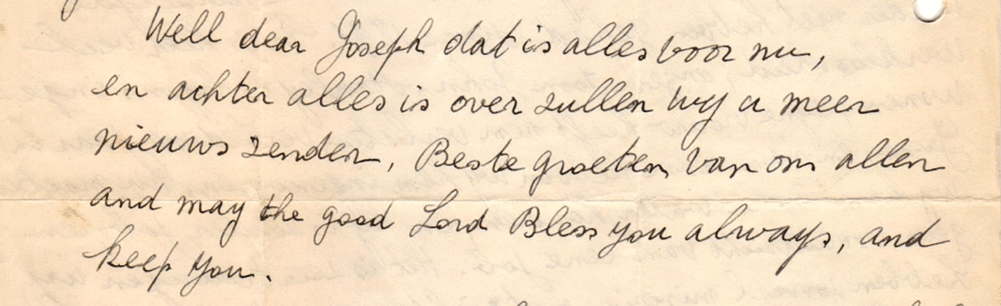

As the title of my second study suggested (From ‟dankgevingsdag” to ‘turkey party”), English words turned up in many different ways in the language of early Flemish Americans. Sometimes these words were given inventive translations, such as drijver for driver or trafieklaan for traffic lane. Other times, English and Dutch were combined into hybrid words, such as farmgerief (farm equipment) or haardresser (hairdresser). Every so often, full English expressions were included, as in a 1950 letter from W. and S., ending with: “Beste groeten van ons allen (best regards from all of us) and may the Lord bless you always, and keep you.”

In letters to their home country, immigrants used English words to show that they had embraced their new world

In letters to their home country, immigrants used English words to show that they had embraced their new world © Private archive

While English was clearly present, it was still fairly limited in scope. I found about eighteen English occurrences per thousand words of text. Enough to stand out, but not enough to dominate the Dutch language. The majority of words reflected the everyday American experiences of the migrants. The newspapers featured many agricultural terms, such as farmer or hooirake (hay rake), political terms such as county board or townontvanger (town tax collector), as well as newer terms such as television or refrigerator. In personal correspondence, topics centered on daily life, health, and food. Think of words like saloon, dankdag (from Thanksgiving), een koude (from a cold), baken (to bake), and ijscream (ice cream).

English in moderation

In my final study, I examined how the use of English differed according to individual characteristics. Who used the most English, and why? It comes as no surprise that Flemings who had lived in North America for more than ten years incorporated English into their speech most frequently. Naturally, the longer someone resides in a foreign country, the more they adopt the language and customs of their new environment.

Who the letter was addressed to also mattered. Letters to parents, siblings, or children included significantly more English than those sent to more distant relatives like aunts, uncles, or cousins. Presumably, the migrants wanted to show their closest relatives not only how they were doing, but also how they had changed.

By regularly using English words, they made it clear that they had embraced their new world and were part of it. My final observation was that Flemings living in rural areas used less English than those living in cities. This difference can likely be explained by the stronger cohesion of Flemish-American circles in rural areas. In cities, there was more frequent contact with other migrant groups, and English quickly became the common language.

Language as a mirror of migration

This research brought to light a largely forgotten part of history: the linguistic development of Flemish migrants in 19th- and 20th-century North America. By exploring how Flemings in North America thought about language and used it in everyday life, a recognisable migration story emerged: a story of people far from home, navigating between holding on to what is familiar and embracing a new world. This dual desire was reflected in their language use. In newspapers, letters, and postcards, familiar Dutch words appeared alongside new English influences. Early Flemish migrants copied, translated, and mixed words: not only out of necessity or practicality, but also as a form of creativity and self-expression.

The Belgian Club in Manitoba, Canada

The Belgian Club in Manitoba, Canada © RV

Language is more than just a means of communication; it provides stability amid change and plays a central role in how people shape their identity. The Dutch used by the migrants evolved alongside their journey, adapting to the reality of their new environment. What started as a Flemish identity gradually became a Flemish-American one. Between two languages and worlds, the Flemish migrants developed a unique register, a linguistic trace that not only recounts their story but also makes it tangible.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.