What if We Were to Speak Skepi Dutch?

Researchers from universities in Krakow and Stockholm have discovered 250 new words of Skepi Dutch in a nineteenth-century missionary diary. And that’s a big deal. This creole language, which is related to Dutch, is now extinct, but was once spoken in the Essequibo area of what is now the Republic of Guyana.

From what we know, three languages related to Dutch were spoken in the Caribbean. On the U.S. Virgin Islands, once known as the Danish Antilles, inhabitants spoke Virgin Islands Dutch Creole, also known as Negerhollands (Negro-Dutch). Much has been written in and about this language since this eighteenth century. In present-day Guyana, inhabitants spoke Berbice Dutch and Skepi Dutch.

In the November issue of Journal of Pidgin and Creole Studies, Bart Jacobs and Mikael Parkvall present a new source of Skepi Dutch, that almost doubles the vocabulary of the Skepi that we know.

In the Cadbury Research Library of the University of Birmingham, Jacobs and Parkvall found, as an attachment to a 650-page diary, roughly 40 pages full of entries in various Indian languages such as Carib and Akawaio, but also in English and, yes, in Skepi.

Essequibo

Bart Jacobs and Mikael Parkvall are no strangers to the world of Creolistics. For example, Jacobs (Romance Linguistics, the University of Krakow) researches the origins of Papiamentu and, together with Marijke van der Wal, describes the oldest texts in this language, found in the Letters as Loot Corpus. Parkvall (Linguistics, Stockholm University) has been critically evaluating the genesis of creole languages for years. Yet he has also studied, for example, the very nature of pidgin and creole languages.

Before I speak about the spectacular find of Jacobs and Parkvall, I have to tell something about the mysterious Skepi – We know almost nothing about this language. In 1974/1975, Guyanese linguist Ian Robertson (University of the Westindies, Trinidad) discovered that two other languages related to Dutch were spoken in Guyana. One of them, Berbice Dutch, still had speakers at that time, but the language was already announced dead. Several informants turned out to be rememberers of another creole language, which they called Skepi. In the older sources that I will mention later, there is always talk of Dutch Creole or Dutch Patois. This language was spoken near the mouth of the Essequibo River, in the former Dutch colony Essequibo/Isekepi; hence Skepi.

1798 map of the colony of Essequibo, founded by the Dutch in 1616 at the mouth of the river of the same name.

1798 map of the colony of Essequibo, founded by the Dutch in 1616 at the mouth of the river of the same name.© Nationaal Archief

Dutch Patois

These informants helped make it possible for Robertson to write down a few sentences and roughly 200 words of the Skepi. In several articles, these are discussed, but most clearly, they are listed in a comparison of the so-called Swadesh lists of the three Caribbean Dutch creole languages (read here).

But then again, what can we do with the information of rememberers? Is it reliable? Are the words well remembered? What do they actually know about the history and origin of this language? At first glance, no other Skepi text appeared to have been published. However, when Marijke van der Wal found a creole phrase in a Dutch letter from Essequibo in the Letters as Loot Corpus, the language appeared to exist at least from 1780 onwards. (Letters as loot, letter of the month December 2013).

I too searched for information about this special language, especially because the comparison of the glossaries showed that Skepi is more closely related to the Virgin Islands Dutch Creole than to the Berbice Dutch spoken two rivers down. In the Guyanese records, which are available online, I unfortunately only found one new word: Siripi (meaning ‘Greenheart [or tree species]),’ which would be Dutch Patois, but has been borrowed from the Caribbean. The nineteenth-century archive documents do contain information about the use of Dutch Creole in the former colony of Essequibo. For example, a report on the determination of the border between Venezuela and Guyana contains a paragraph about Dutch Creole. When the inhabitants of the disputed border area spoke Spanish in everyday speech, their area would belong to Venezuela, but when they spoke Dutch Creole, the area would belong to the English Guyana.

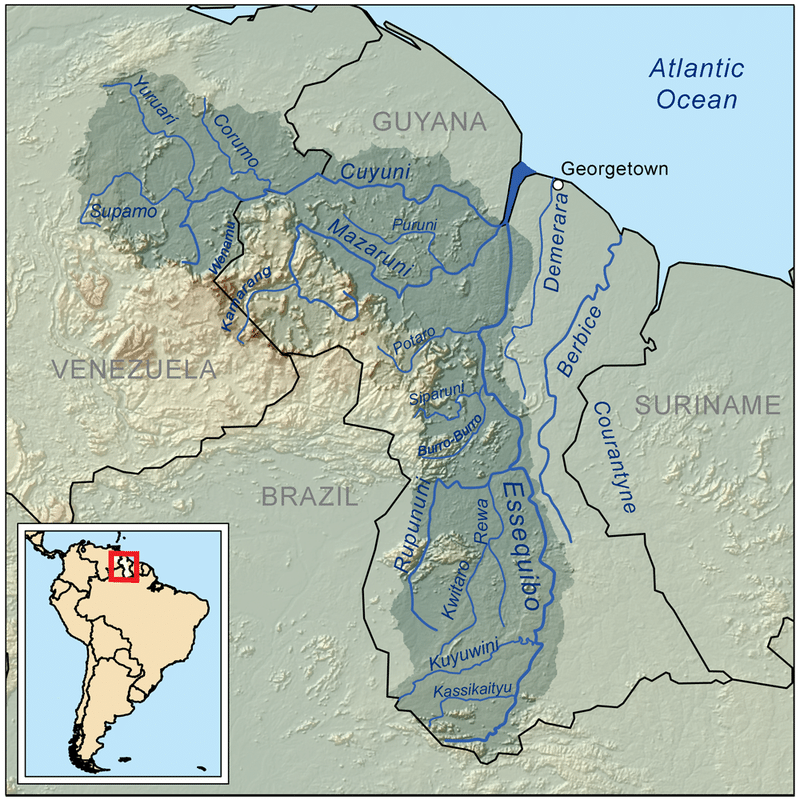

A map of the Essequibo River drainage basin in Guyana. From 1616 to 1814, the Dutch controlled this area in the colony of Essequibo. The Skepi language is a remnant of this colonial past.

A map of the Essequibo River drainage basin in Guyana. From 1616 to 1814, the Dutch controlled this area in the colony of Essequibo. The Skepi language is a remnant of this colonial past.© Wikipedia

Diary of missionary

Jacobs and Parkvall do not reveal how they found their source in the article. Too bad, I do like the description of such a search. We are presented an extensive short note that describes metalinguistic circumstances. The diary was kept by the missionary Thomas Youd who arrived in Guyana in 1832 to do missionary work among the indigenous people. Within three weeks, he would have learned Dutch Creole at Bartica, a large settlement on the left bank of the Essequibo River. He used this language during his services and also translated the English sermons of his colleague/pastor Strong to Creole. Additionally, in other parts of the diary, you can find regular references to the use of Creole. The diary ends in 1842, when Youd died under strange circumstances.

In the next paragraph, Jacobs and Parkvall discuss the character of the manuscripts, which is illustrated with three pictures. They also mention how much Skepi material has been found: 250 words in different parts of speech, two-thirds of which have not been published before by Robertson. Furthermore, the text contains 120 Creole phrases.

Finally, they present the text corpus, in which they provide the Skepi words with a translation and (presumed) origin. They note whether the word has already appeared in Robertson’s publications, but also how reliable they find their translation and origin.

Some examples of phrases:

moi dak fandak!

‘A good day, today!’

(translated by Youd, Jacobs&Parkvall 2020: 367)

Cabba

For native Dutch speakers, this seems a readable text. In the following examples, you can see two aspects that can also be seen in other Dutch-related creole languages. The negation ne is placed in front of the finite verb form instead of at the end. Although personal pronouns etymologically originate from Dutch, they are used in a different way in this creole language. You can see em (“third person singular,” Dutch “him”), and you (pronounce as /you/, “second person singular,” (Zeelandic) Dutch, “joe (jou)”), where in Dutch, you would use him and you respectively.

Em ne ben you em ben ander domine de swarte domine bi de Fort

‘It is not you, it is the other minister at Fort Island’

(translated by Youd, Jacobs&Parkvall 2020: 367)

In the next sentence, you can see a remarkable word that can also be found in the Virgin Islands Dutch Creole.

Cabba em ben de swarte domine bi de Fort

‘Friend, it is the black minister near Fort Island’

(translation originally published in Youd, Jacobs&Parkvall 2020: 368)

Jacobs and Parkvall write that the translation by Youd originally started with No

instead of Friend. Since the word cabé in the Virgin Island Dutch Creole can also mean “friend,” that might be a good adaptation. However, in many creole languages, kabba is used to mean “finished.” Could Youd or his conversation partner have used “ready, it is the black minister near Fort Island” as some sort of closure of a discussion?

New version

Almost every word is a piece of preserved seventeenth-century Dutch, and, just as in the Virgin Islands Dutch Creole and the Berbice Dutch, dialect characteristics of Zeelandic can be identified too.

Jacobs and Parkvall are not lying idle and announced their next publication in several parts of the article: New insights into the phonology, grammar and lexicon of Skepi. Undoubtedly, this piece will also give their other research a boost. For example, three years ago, Peter Bakker (Aarhus University) described linguistic relationships between Skepi and other Dutch related creole languages based on the language material that was available at the time. The text corpus that he now uses for that purpose has almost doubled in size, which begs for a new version.