#25 – Pheasant Fealty

After the Treaty of Arras in 1435, the international policies of the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good, had to overcome several hurdles if he was to achieve his aim of obtaining as much territory and autonomy as he could. Despite his reconciliation with the king of France, the two cousins would continually be at each other’s throats and on the brink of breaking into warfare again.

In 1441 Philip became the regent for Luxembourg and this irked the dignity of certain powerbrokers in the Holy Roman Empire who had their own eyes on the domain. Because Philip was a French prince who ruled imperial territories, he had to rely on his usual tactics of over-the-top extravagance and relationship-building to navigate through the political awkwardness that this caused.

He successfully made moves designed to maintain his autonomy as a prince of Christendom and from the 1440s harboured the idea of elevation to a kingship. This would come close to materialising several times, however, as has been the way since Charlemagne’s empire was split up between three brothers all those centuries ago, Philip found that being stuck between France and the German Empire left little room for absolute low country autonomy.

Congress of Arras

In the summer of 1435, the Congress of Arras was convened in the capital of the Burgundian-ruled territory of Artois. Philip the Good had two intentions for the negotiations, which were to establish a lasting peace between France, and England as well as to reconcile Franco-Burgundian relations. The English deputation at Arras was displeased with any idea of French and Burgundian love, as the two enemies were currently battling it out in parts of France. The English left petulantly in September having come to no peace with France, and with the Burgundian-English alliance in tatters. The French embassy then endeared Philip and his entourage to stay and conclude peace between himself and the king.

Small illustration from Vigiles de Charles VII (c. 1484) depicting the Congress of Arras

Small illustration from Vigiles de Charles VII (c. 1484) depicting the Congress of Arras© Bibliothèque nationale de France

The resultant Treaty of Arras effectively brought an end to the internal open conflict between Armagnac and Burgundian forces in France. But crucially, it disavowed Philip of his vassalage to King Charles VII for the remainder of their lives. As long as either of them was alive, Philip did not have to pay homage to Charles VII as his liege. With this, Philip achieved something that many other Counts of Flanders would have dreamed of, but which none besides him had managed – real independence from France.

It also marked a major turning point in the Hundred Years’ War. Even though England held a very strong position in France, at this time even controlling Paris, it would decline from here on in. Despite the Treaty of Arras, the relationship between Philip and Charles VII would never go beyond symbolic platitudes, such as exchanging god-father status and marrying their children to one another. In reality, Charles VII’s main objective was to break the Anglo-Burgundian alliance. Once this had been achieved, his life-long held hostility to Burgundy resumed and grew, as he became more and more bitter about certain demands that Philip had made in the treaty.

Ecorcheurs

Charles VII (1403 – 1461) was King of France from 1422 to his death in 1461. His reign saw the end of the Hundred Years' War and a de facto end of the English claims to the French throne.

Charles VII (1403 – 1461) was King of France from 1422 to his death in 1461. His reign saw the end of the Hundred Years' War and a de facto end of the English claims to the French throne.© Wikipedia

As a result of the agreement, Charles VII would remain angry well into the 1440s and seemed willing to obstruct and poke at Philip whenever he could. One of the most evident expressions of this was the arrival of Ecorcheurs into Philip’s domains, which were armed bandits, remnants of now unemployed soldiers from the discontinued Armagnac-Burgundian civil war which had been raging for so long. With nothing to do they kind of roamed around, taking stuff from people and became an identifiable part of Charles VII’s regime. Although Charles frequently condemned them, he did little else to discourage them. Assumedly he preferred them to be keeping Burgundy on its toes rather than rampaging through French lands. They became referred to as les gens du roi – Men of the king.

Acquiring Luxembourg

Through the 1440s Philip and Charles VII had constant disagreements over various land titles, and Philip was apparently constantly worried about the prospect of a French invasion of his lands. However, Burgundian domains now stretched way beyond the suzerainty of the French throne and into the realm of the other great lord to whom he had to pay due respect, homage and taxes; the Holy Roman Emperor.

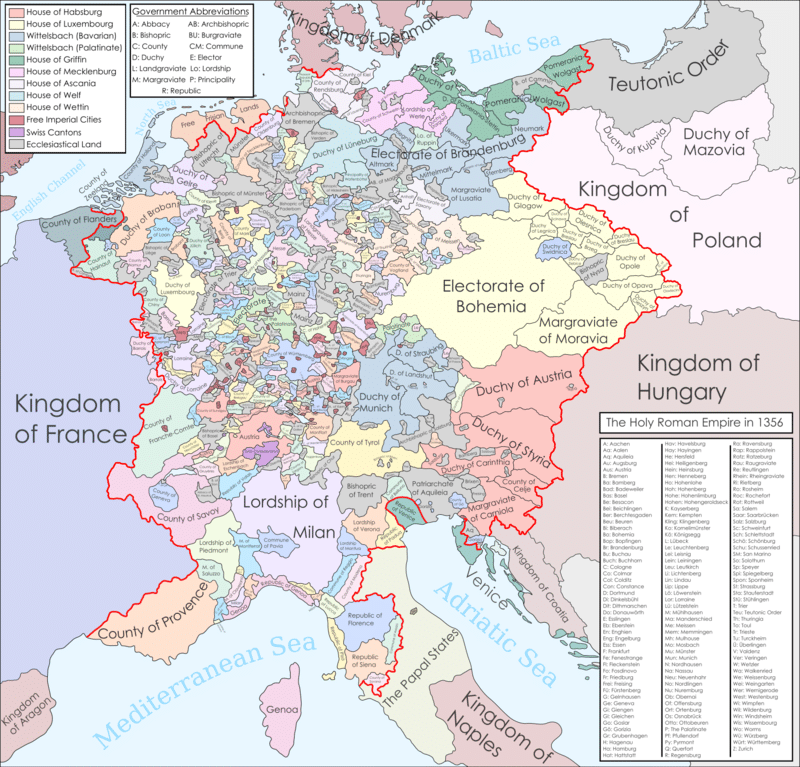

The Holy Roman Empire was in fact about to hit a watershed moment. For nearly a century the House of Luxembourg had sat atop the imperial throne. The political mire of imperial rule, however, was always tied up with the incessant goings-on in the Church hierarchy, so getting the support of enough electors to become emperor was highly dependent on other political alignments.

Page from the Golden Bull manuscript of King Wenceslaus, about 1400

Page from the Golden Bull manuscript of King Wenceslaus, about 1400© Austrian National Library

Before the Golden Bull of 1356, when guidelines were established on how the emperor should be elected, until 1437, the Luxembourg and Wittelsbach families had held most of the important titles. When the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg died in 1437, it would be the first real test of those guidelines. In 1440 Frederick III was elected. He was from a family who had gotten themselves the King of the Romans title four generations previously and had long been in the upper echelons of imperial socio-politics. The Habsburg family had finally ascended to the imperial throne. It would take fifteen years before the crown was officially given by the pope to Frederick III, but at that time he was the main man in the empire. The Habsburgs, from then on, would retain the imperial crown, which would eventually become the Austrian crown, for nearly five hundred years.

The current ruler of Luxembourg was Duchess Elizabeth of Goerlitz. Her uncle Wenceslaus had given her that title, those lands and the income which it generated in the negotiations which had taken place during her marriage to Anton of Brabant. But if Wenceslaus ever wanted them again, he could buy it all back, and also the title would eventually pass on to his children. Wenceslaus’ brother, Sigismund, however, just pretended that actually, he was the Duke of Luxembourg. Elizabeth survived Anthony, and then also survived her second husband, John of Bavaria. Wenceslaus also died without any children, meaning that the answer to the question of who exactly was the ruler of Luxembourg depended on who you asked.

The Holy Roman Empire when the Golden Bull of 1356 was signed

The Holy Roman Empire when the Golden Bull of 1356 was signed© Wikipedia

Many attempts were made by various people to take over administration and eventual inheritance of her lands. Elizabeth was broke and mortgaging her lands to another ruler was her best option, and many other rulers sought to attain this. Three people came out as frontrunners, William of Saxony, Jacob van Sierck, Archbishop of Trier, and finally, Philip the Good. It ended with the Burgundian army marching into Luxembourg without any resistance.

Over the 1440s Philip and Frederick proceeded on a merry diplomatic dance with one another that did not reap any direct results. In November 1442 they met at the imperial city of Besançon, in the Franche-Comte of Burgundy. Philip sought to end the stalemate over Luxembourg and to attain imperial sanction of his rule over his northern low country territories, Brabant, Hainault, Holland & Zeeland, which in the end resulted in nothing.

Fall of Constantinople , The crusades and the Feast of Pheasant

In 1453 calamity shook Christendom. The Ottoman Turks, whose expansionism on the Anatolian peninsula had been threatening the West, broke through the gateway between the two worlds and managed to conquer Constantinople. Philip had been fostering his good relations with the controversial Pope Eugenius IV, and had been talking up to join a crusade himself. After all, Philip’s father had led a disastrous failure of a crusade and still come out of it with more prestige and honour than he had gone in.

Philip the Good (1396-1467)

Philip the Good (1396-1467)© Wikipedia

Philip was all about gaining prestige and honour. Even though he was busy with acquiring Luxembourg and dealing with Ghent, by the end of the year Philip had managed to subdue both and turned his attention towards a crusade, His approach was pretty true to Philip’s fashion; he threw the party of the century, with a whole lot of symbolic grandeur.

In February 1454 Philip held an event in Lille which has become known as the Feast of the Pheasant. This was a grand banquet held for his court, complete with a viewing gallery for those who weren’t special enough to be selected to sit at one of the three tables. The details of what went down have been preserved by court chronicler Olivier de la Marche in his memoirs, and they provide us with an extraordinary insight into what exactly occurred.

Anonymous sixteenth-century painting showing participants of the Feast of the Pheasant

Anonymous sixteenth-century painting showing participants of the Feast of the Pheasant© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Most historians seem to think that although de la Marche may have been looking back on the event with some rose coloured glasses when describing it, the fact that he was part of the organising committee and that he took part in the festivities, at one point entering into the dining hall riding on a mechanical elephant, means that we can probably trust a lot of what he says.

After the grand party, Philip was summoned by Frederick III to the Imperial Diet at Regensburg, to take place in April. The main discussion point was to make arrangements to go crusading. His trip to Regensburg was one of only three major journeys he ever made outside of his lands. He took his time, making certain visits along the way and being accompanied by all types of high lords, most notably the Duke of Bavaria who travelled with him for nearly a week.

Along the way Philip had his entourage splashing cash all over the place, and he paid the inns he stayed in handsomely to prominently display his ducal banners. He made sure that his journey and arrival made as big a statement as it could, and he was clearly set to be the most eminent person at the Diet next to the Emperor. As for Frederick III, he did not turn up to his own party, as he had to hurry off on imperial business and sent representatives instead; namely to give aid to the regent of Hungary, who was dealing with internal strife and having a terrible time of it against the Ottomans. Frederick’s absence meant that there would be no certainty of a crusade, but more importantly, there would be no discussion about the things that Philip really cared about; the settlement of Luxembourg and imperial consent to his rule over the northern low countries.

In the end, Philip would leave Regensburg with high esteem but the crusade would never happen. No matter how willing Philip was, he could not get the support of his arch-enemy and cousin, Charles VII of France. Philip probably felt that if he could not unite with France against a common enemy who was not the English, but rather non-Christian people on the other side of Europe, then it would be folly to go without French support and leave his domains vulnerable to French attack. Furthermore, what if the rebellious nature of low country towns flared up while he was away? That could be disastrous. At the end of the day, there was no prince fit enough to gird him in the endeavour, and so he never went.

The stalemate with the Emperor over Luxembourg and the other low countries would continue for years. In 1463 Frederick once again suggested a crown and, once again, the terms were not to Philip’s liking. However during these sessions, certain negotiations began that would, it turns out, bear much fruit. A marriage was proposed that would be between Frederick’s son, Maximilian of Habsburg and Philip’s granddaughter, Mary of Burgundy. This marriage alliance will open the door for the Habsburg take-over of the Netherlands, and prove a defining moment in its history that we are approaching.

Sources

- The chronicles of Enguerrand de Monstrelet

- Burgundy and the Empire in the Reign of Charles the Bold by Laetitia Boehm

- The Deeds of Jacques de Lalaing: Feats of Arms of a 15th Century Knight by S. Matthew Galas Esq.

- Political narrative and symbolism in the Feast of the Pheasant (1454) by Rolf Strøm-Olsen

- The ideology of Burgundy by D’arcy Jonathan Dacre Boulton and Jan R. Veentra, in Brill’s studies in intellectual history by A.J Vanderjagt et al

- Court and civic society in the Burgundian low countries 1420-1430, translation and annotation by Andrew Brown & Graeme Small

- The failure of Philip the Good to fulfill his crusade promise by Kelly DeVries in The Medieval Crusade By Sewanee Medieval Colloquium

- The Papacy and the Levant, 1204-1571: The fifteenth century by Kenneth Meyer Setton

- Philip the Good: The Apogee of Burgundy, Volume 3 by Richard Vaughan

- The Promised Lands by Wim Blockmans and Walter Prevenier

- Magnanimous Dukes and Rising States: The Unification of the Burgundian Netherlands, 1380-1480 by Robert Stein

- Charles the Bold, the Last Duke of Burgundy

by Ruth Putnam