Romantic Anguish in China: a New Slauerhoff Translation

Dutch literature is notorious for its lack of a romantic movement. Writer and maritime doctor J. Slauerhoff (1898-1936), however, published a supremely romantic novel in 1934: Adrift in the Middle Kingdom (Het leven op aarde), set in Interwar China. This is now available to English-language readers, in an accessible translation by David McKay.

Slauerhoff is primarily known for his bitter poems, railing against the social control and inhibition to pleasure which he felt characterised the bourgeois Netherlands. He figures in his own poetry as an aggressive rebel, outcast and eternal drifter. As translator McKay’s ingenious title Adrift in the Middle Kingdom indicates, in this novel, Slauerhoff sticks to the same course.

The book forms a sequel to Slauerhoff’s first novel, The Forbidden Kingdom, which appeared in English previously, with Pushkin Press. In Adrift, ship’s radio operator Cameron, weary of life at sea, convinces himself he will find contentment on land. He jumps ship in the Shanghai-like city of Taihai and through a series of encounters with men and women of a less high-minded bent, he gradually travels westward, to the Himalayas, where he may or may not find his enlightenment.

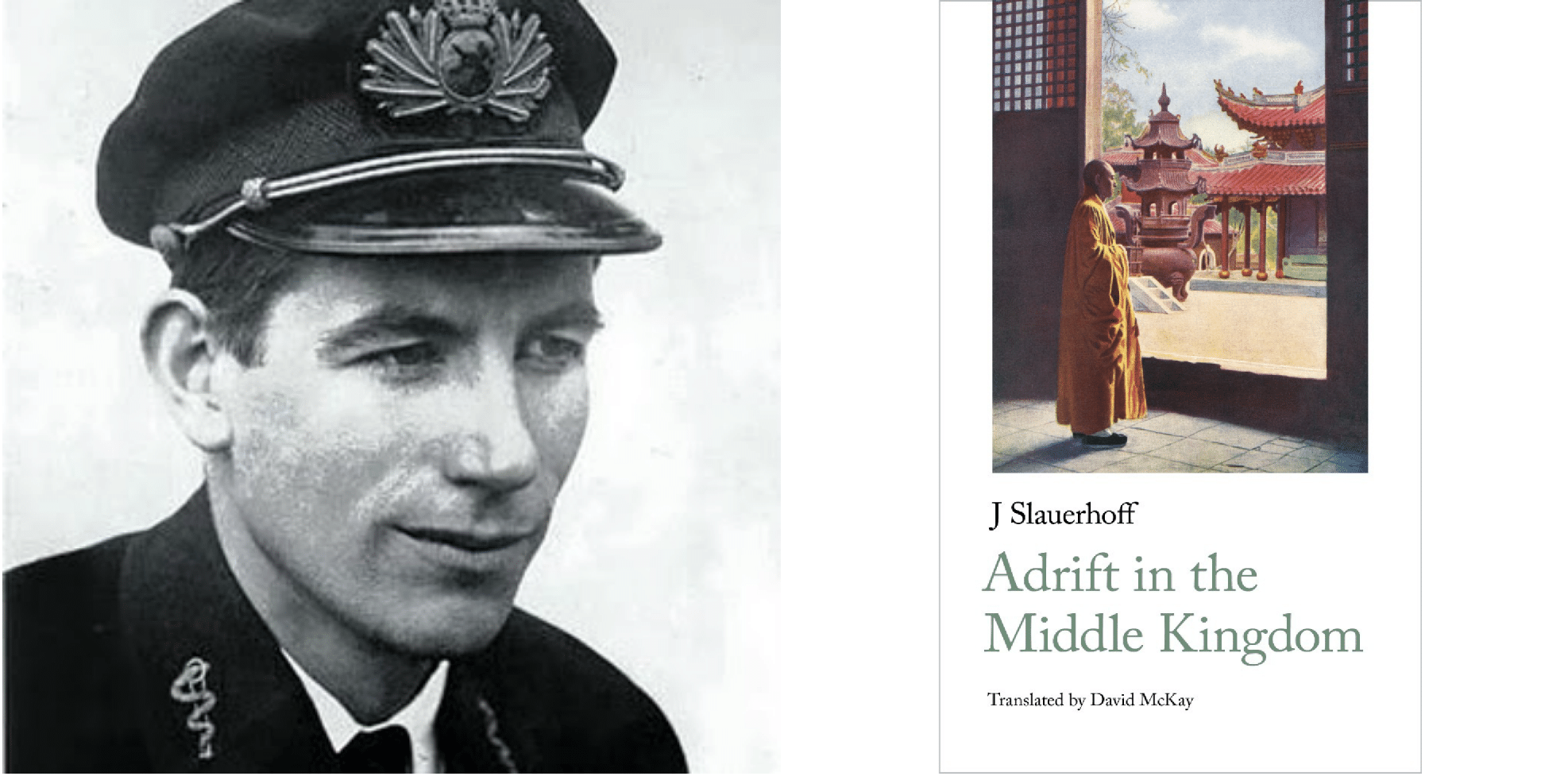

Jan Jacob Slauerhoff (1898-1936), ca. 1930

Jan Jacob Slauerhoff (1898-1936), ca. 1930© Magazine Fleurs du Mal

McKay has delivered a fluent English text, choosing to smooth out Slauerhoff’s terse style. Though at times McKay gets the narrators’ brevity across using well-chosen alternative constructions that sound more acceptable to the English ear, at other times the rather unforgiving original has been considerably softened. ‘Flaccid’ eyes turn ‘mild’, ‘greasy’ hair ‘shiny’, Slauerhoff’s gritty use of participles disappears, and harsh strings of main clauses with little variation in word order and no connectives become a more pleasantly varied text. While surrendering some of the novel’s literary interest, McKay’s decision no doubt offers Slauerhoff a wider readership.

Adrift is a classic orientalist story, projecting northern-European anxieties and social (self-)criticism onto an exotic eastern world. Priests are self-serving, merchants ruthless, monks either despicable or holy. In particular, the novel offers variations on nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century ideas about the decline of the West and a more enduring eastern world, frozen in time.

Adrift is a classic orientalist story, projecting northern-European anxieties and social (self-)criticism onto an exotic eastern world

It is true that Slauerhoff had visited the major Chinese ports and took a serious interest in eastern philosophy and history. He is also sufficiently self-aware as an author occasionally to shatter his own romantic creations, for instance the image of the oriental sage All-But-One, which leads to some tragically funny moments in the novel. More generally, a scattering of humour relieves what is on the whole a rather heavy-handed text. Cameron visits a Himalayan cell ‘where ten or twelve hermits live together, fearless, invulnerable, devoting all their time to higher meditations and nothing else, providing the instant telegraph service of mind-transference. They do not clothe themselves, staying warm not through exercise but through the friction of thoughts.’

A view of Shanghai's Bund in 1928

A view of Shanghai's Bund in 1928Still, this story is first and foremost the romance of the eternal drifter, to which China forms only the necessary backdrop. Although Slauerhoff expert Arie Pos’s introduction calls Adrift an unconventional novel, ahead of its time, it strongly resembles the classic romantic stories of elite ennui which have formed a mainstay of western literature since Byron and Baudelaire. No doubt, Cameron’s inability to settle down to a content community and family life has everything to do with his recognition of the pain of the world. As befits a concerned Interwar author, Slauerhoff shows an interest in the suffering of the poor farmers and city-dwellers who furnish his protagonist’s world. Yet his protagonist remains an observer: the misery of 1920s China, run over by European colonisers and Asian armies, by floods and famines, where gruelling work conditions and casual violence form the daily – and nightly – reality of the majority of the population, which is expounded in short naturalist scenes (to which Wendy Gan’s (University of Hong Kong) introduction offers a useful context), does not really touch Cameron. He passes ‘a hairnet factory where six-year-old girls operate the looms and sometimes die at those looms like butterflies in a web that they, in their floundering, have spun.’ The perishing girls offer a beautiful poetic setting for Cameron’s existential journey. But they themselves are not dwelled on.

Jan Jacob Slauerhoff wearing a kimono. Photo probably made in the Netherlands, shortly after Dec. 1927.

Jan Jacob Slauerhoff wearing a kimono. Photo probably made in the Netherlands, shortly after Dec. 1927.© Nederlands Letterkundig Museum

Thus, Cameron enjoys the dubious privilege of remaining an outsider, someone with few responsibilities. As Cameron himself concludes: ‘I took no further part in life on earth.’ His distaste for the humdrum and pain of the ceaseless creation and destruction of life on earth forms the central theme of the novel, reflected in the Dutch title. It remains unclear to what extent Slauerhoff was nevertheless aware of his protagonist’s unwitting contributions to this life. Had he been a different author, we might have taken Cameron’s matter-of-fact participation in sexual violence, for instance, as intentionally ironic. (Only on one occasion does the text distance itself from Cameron’s behaviour.) As it is, the frequent acts of sexual aggression which Cameron either observes or perpetrates, seem meant merely to underline his detachment from normative social values: the book romanticises his behaviour as a social outcast. Similarly, Slauerhoff uses prostitution to lament the emptiness of modern life and love, without finding a cause for concern in the more fundamental issue that the prostitutes in his story enter their line of work by force – a practice which his novel normalises. Although endemic, rape and slavery did not go unchallenged in Interwar China: they did not form part of an unchanging and unchangeable Orient. A different life on earth was certainly thinkable. Yet in Slauerhoff’s tale, the wretched are there to underline the book’s mood and philosophy. ‘On a night like this, living things long for destruction.’

Apart from an almost magical-realist final chapter, Adrift therefore remains a somewhat old-fashioned novel. Since its publisher, the young Handheld Press, has set itself the admirable task of making modernist fiction more widely available, I would like to use this opportunity to share a secret: greater literary gods such as Blaman, Bordewijk, Theo Thijssen or Carry van Bruggen have hardly been translated yet…

J. Slauerhoff, Adrift in the Middle Kingdom, translated by David McKay (Bath: Handheld Press, 2019)