‘Rozeke’ by Guillaume Van Der Stighelen: The Eternal Battle Between Heart and Mind

In Rozeke, we follow the ups and downs in the life of an Antwerp entrepreneur in the Belle Époque. In figurative language, Guillaume Van der Stighelen describes how his namesake climbs the social ladder, but struggles on a personal level with himself and those around him.

“If I had known it would be easy, I might have started writing novels earlier,” 67-year-old debut author Guillaume Van der Stighelen tells us in the first episode of our new podcast First Book (in Dutch).

Guillaume Van der Stighelen

Guillaume Van der Stighelen© Standaard Uitgeverij

That may sound a bit arrogant, but it is not what Van der Stighelen means. He mainly means to say that he had a great time writing his hefty debut, because he loves making up stories. And it shows: the author is a compelling storyteller.

Antwerpian Van der Stighelen has been writing professionally all his life. First as a copywriter in the world of advertising: in Flanders, people know him from the ad “Home is where my Stella is” (Mijn thuis is waar mijn Stella staat), in the Netherlands, it’s “It smells like… Douwe Egberts” (Het ruikt hier naar … Douwe Egberts). He followed this by writing opinion pieces and columns for the daily newspapers De Morgen and Gazet van Antwerpen.

After the sudden death of a son in 2011, he penned a fine volume of poetry, but only in recent years has he ventured into prose. Primarily for himself, before friends encouraged him to approach a publisher.

A great-grandfather and a great-grandson

Rozeke tells the story of Guillaume Van der Stighelen, the great-grandfather after whom the writer is named. Although the story is based on that man’s life very loosely. Apart from some minor factual details and the occasional family legend passed down through generations, not that much was known about him. Luckily for the great-grandson, who could thus unleash his imagination to the full.

The novel’s character Van der Stighelen is a plumber in mid-nineteenth-century Antwerp. At the time, pipes were being laid for gas lighting in houses and streets. During one of the severe cholera epidemics, a doctor suggests to him that the pipes could also be used to supply clean water and drain dirty water, which was a revolutionary idea.

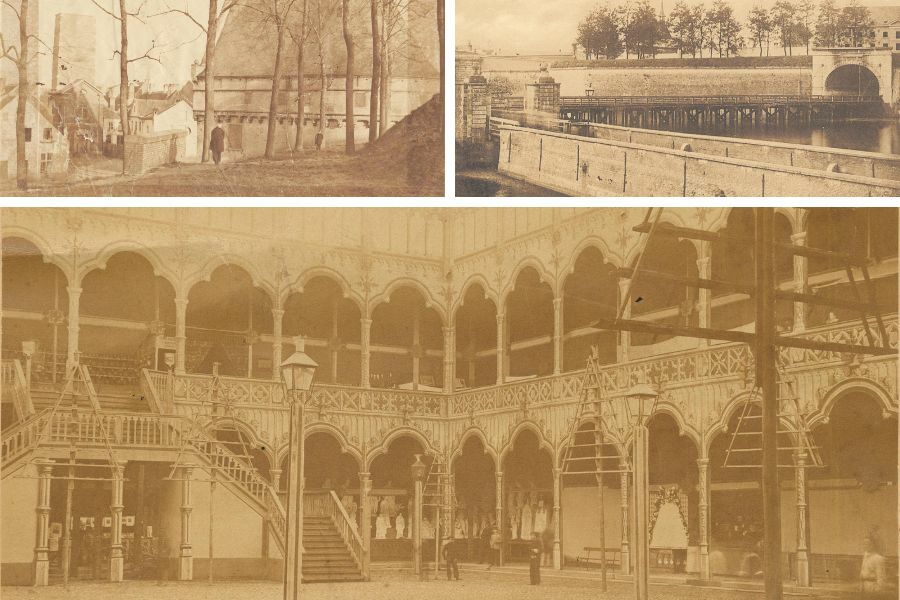

Antwerp in the nineteenth century, with a view of the Blue Tower on Sint-Jorisvest at the top (1863), the Rijnpoortvest (c. 1860) and the newly rebuilt Handelsbeurs in 1875 at the bottom.

Antwerp in the nineteenth century, with a view of the Blue Tower on Sint-Jorisvest at the top (1863), the Rijnpoortvest (c. 1860) and the newly rebuilt Handelsbeurs in 1875 at the bottom.© Felix Archives, Antwerp

The young entrepreneur starts focusing on sanitary installations. Thanks to increased awareness of hygiene and a contract with the city of Antwerp, Etablissements Guillaume Van der Stighelen becomes a thriving business, and its namesake a prominent citizen.

Business-wise, Van der Stighelen is successful, but otherwise life does not always spoil him, he thinks. Sometimes this is justified, sometimes not. He is not spared disaster, and that too marks him. He looks around him, at the trajectory of less successful relatives and peers, and decides that “the heart” sometimes wants what the devil wants, inspired by Baudelaire. From now on, the sensitive young man decides to use his mind when making decisions. In the eternal battle between heart and mind, he has definitively taken sides. He thinks.

King on the loo

Thanks to these rational choices, he is steadily climbing the social ladder, but in his personal life, Guillaume Van der Stighelen continues to struggle. The relationship with his wife and sons is one of much trial and error, and he never really gets the emotional dilemmas he wrestles with out of his system.

Author Van der Stighelen describes his great-grandfather’s stumbling life’s journey with compassion and empathy, and without judgement. He does so in language that is figurative and sometimes vulgar; after all, the author did train as a screenwriter. Rozeke features some delightful scenes, such as the guided tour of King Leopold II at the 1894 World’s Fair in Antwerp, when even the king must visit the smallest room eventually… Luckily, Van der Stighelen has just installed his new plumbing for demonstration purposes.

Author Van der Stighelen describes his great-grandfather’s stumbling life’s journey with compassion and empathy, and without judgement

Van der Stighelen the writer has nicely dosed the historical facts. These direct the comings and goings of great-grandfather Guillaume. As do the many women in the book. His wife plays a defining role, as do his daughters-in-law, though to a slightly lesser extent. His own strict mother is the polar opposite of a more libertine aunt, but they both provide inspiration.

That too is a theme in the book: how the establishment deals with all these new developments. On the business front, Guillaume is a pioneer with his plumbing, but socially he shifts from being a bohemian to a bitter ultraconservative.

In this way, Rozeke is also a universal story. The echoes with today’s society are easy to make, with a critique of capitalism, fear and loathing of newcomers, and the struggle between conservatism and innovation… Van der Stighelen writes it all down tastefully, with humour, empathy, and pace.

Guillaume Van der Stighelen, Rozeke, Manteau, Antwerpen, 2023, 464 pages.

Excerpt of ‘Rozeke’, as translated by Elisabeth Salverda

“The blue death, Netje! The blue death is back! There’s a ship flying the yellow flag and all of Rietdijk is infected. Suske is probably already done for. I was lucky I stayed at the door. He was in the attic, cried his mother, blue from top to bottom. The Doctor pretends not to know anything about it, but he knows all too well. The council has told him to keep quiet. So as not to frighten the people, and to give the gentlemen of the city time to leave in their carriages before the people do not let them pass.”

Netje turns pale. The blue death. She remembers her parents’ stories. She was born in the middle of the first cholera epidemic, and she survived as if by a miracle. But the stories of desiccated blue faces wandering the streets at night, infecting everyone, those have stuck in her head.

“Come, help pack up, we’re off, before they close the city gates.”

Loaded up by the front door is the cart Docus has bought from a Waas milkman on the wharf. The two dogs are scratching at the bald spots on their backs with their hind legs.

On top of the cart, Docus has tied two pillows and a basket to serve as a crib for Gwillemke. Docus is helping his Netje onto the cart, when behind him a familiar voice sounds.

“Are you leaving?”

Netje’s mouth falls open. Docus turns and sees Suske scratching his hair. His eyes are thick and swollen in black-blue eye sockets. Noticing his masters’ surprise he touches his eyebrow. There is still a thick crust of blood on it. Suske shrugs his shoulders as if to apologise.

“Our dad. Got in trouble the day before yesterday.”

The boy wipes some snot off his nose with his sleeve. Twelve he is. Or eleven. Who’s keeping score, in the alley? He’s big and strong enough to carry Netje’s ironing around in exchange for a penny and a hearty bowl of soup and bread. A belly roar breaks the icy silence. Netje screeches with laughter. “The blue death!”

She points at Docus, on whom it is quietly beginning to dawn just how he has got it wrong.

“Black eye, indeed!”

Around the corner, her friend Mariette appears with a bucket of mussels and winkles. Hiccupping with laughter, and barely intelligible, Netje tells her that Docus thought cholera was back in town and that the Rietdijk was nearly locked down already.

“I’ve just come from the Koolvliet, I haven’t seen anything out of the ordinary,” Mariette replies with her eyebrows raised high.

“No!” shrieks Netje. “If you want to see something out of the ordinary, there it is, see!”

And as tears roll over her full cheeks, Docus unties the dogs. Maybe it’s not too late to take them back to that milkman on Suikerrui. The villain. How dare he ask so much for two worn-out dogs. If Netje finds out how much he paid for those beasts, he’ll be toast. They’d agreed to save up to put their little Gwilhelmus through school.

There is intellect in his family. It has just never come out. They’ve only one child and Doctor Veraert said no more children. “It’s over,” he said, and Netje wept for a few days. Docus didn’t. Such things happen. People shouldn’t be fainthearted about it. Now he has to take those two fleabags back to the wharf at Het Steen. Hope that farmer from Beveren is still there with his milk.