Written Dutch Originated as a Translation Tool

In the series Babel in the Low Countries, editor-in-chief Luc Devoldere contemplates the way we use language today, but just as easily delves into the past to consult with historical figures and writers who stand guard over language. In this article he goes back to the first written version of the Dutch language.

The very first time we came across a written version of our language was in the shape of a few individual words in glosses, i.e. in the margins, accompanying Latin psalms. This lead us to believe they acted as some type of translation aid. According to Dutch literary historian Frits van Oostrom, Dutch literature actually started out as subtitling.

Justus Lipsius (1547-1606)

Justus Lipsius (1547-1606)© Wikipedia

The original Wachtendonckse psalmen manuscript, named after Liège cannon Arnold Wachtendonk who showed the manuscript in 1591 to Justus Lipsius, professor in Leiden (and would be in Leuven as well later on), dates back to around 900 CE. Lipsius copied parts of the manuscript, which originated from the Liège area.

However, we happened to decide Dutch literature begins with hebban olla vogala, the 11th century West-Flemish monk’s probatio pennae, which he scribbled down, hunched over a manuscript he was instructed to copy in a Kent monastery. In the margins, the young monk captures his longing for love in a text about birds building nest, but he and she unfortunately do not.

Ghent professor Luc De Grauwe tried to demonstrate that this lamentation was wholly or at least mostly written down in the Kentish dialect of Old English. Let us suppose that this is a mixed text: Kentish with a coating of West-Flemish varnish, and/or Kentish with West-Flemish roots. This ‘pen test’ is thus also a probatio linguae, a linguistic experiment.

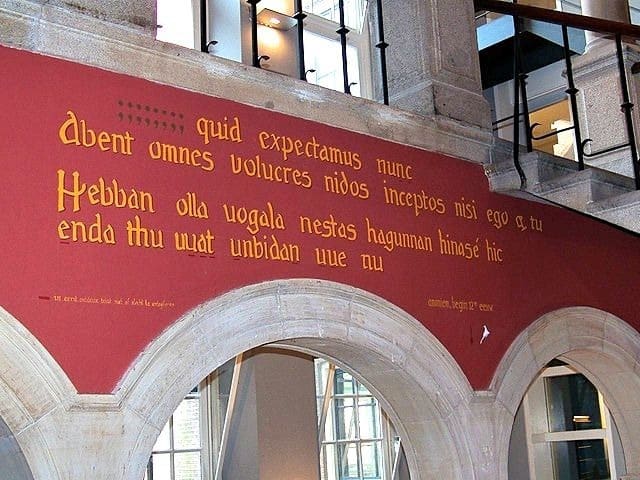

Hebban olla vogala, painted as a poem on a wall in the city of Leiden

Hebban olla vogala, painted as a poem on a wall in the city of Leiden© Flickr

In the course of the 12th century, common vernaculars started to appear in written form next to Latin Continental Western Europe (in England, the vernacular had been around in written form ever since the 7th century). We will, however, have to wait until around 1500 CE for the ‘invention’ of language. By this I mean that at that moment in time people first start to work on a language policy, get involved in language politics, and interfere in the way both individuals and institutions write.

Ordonnance de Villers-Cotterêts (1539)

Ordonnance de Villers-Cotterêts (1539)© Wikipedia

Leuven professor Joop van der Horst only recognises the emergence of standard languages from, what he terms, the Renaissance onwards. He calls this the “linguistic continuum being parcelled in lots”. National borders are increasingly becoming language borders. The 1539 Ordonnance de Villers-Cotterêts, for one, which was issued by the French King Francis I, postulates that every legal document must be drawn up “en langage maternel français et non autrement” (or “in the native French tongue and nothing else”). This will be a lengthy process: between 1500 and 1900, Western Europe sees the birth of nation states France, England, Spain and the Republic of the Seven United Provinces of the Netherlands. Germany and Italy close the line (around 1870). Belgium, which breaks away from the Netherlands in 1830, is a special case – I will get to that later.