Multatuli in the Age of Decolonisation and #MeToo

Now that Multatuli, who was born two hundred years ago, is once again in the limelight, criticism of his ideas also resounds. Was the Dutch writer really such an anti-colonial rebel? And what about his preference for young girls? Elsbeth Etty, president of the Multatuli Society: ‘Multatuli-bashing is a time-worn tradition, and one that keeps his significance alive. I have always found it amusing, without letting it get to me too much.’

What is the present-day significance of Multatuli as a writer and a thinker? On the occasion of Eduard Douwes Dekker’s 200th birthday (1920-1887), this debate has (fortunately) flared up again.

The Dutch monarch Willem-Alexander described his lasting significance during the opening of the 2020 Multatuli year in Amsterdam’s Nieuwe Kerk:

‘2020 is also the year that we celebrate 75 years of liberation. Freedom can only be celebrated when you welcome alternative perspectives in yourself and in society. Multatuli was the contrarian thinker of the 19th century, standing up for human rights and freedom of the press by indicting abuses of power. Multatuli’s true legacy as a writer lies not only in the extent to which he challenged institutional abuses of power, but in the fact that he simultaneously produced the most sublime work of Dutch literature in our canon. That was not his goal, but he did achieve it.’

Elsbeth Etty and King Willem Alexander unveil the commemorative stone of Multatuli in Amsterdam's Nieuwe kerk

Elsbeth Etty and King Willem Alexander unveil the commemorative stone of Multatuli in Amsterdam's Nieuwe kerk© Twitter / Arthur Japin

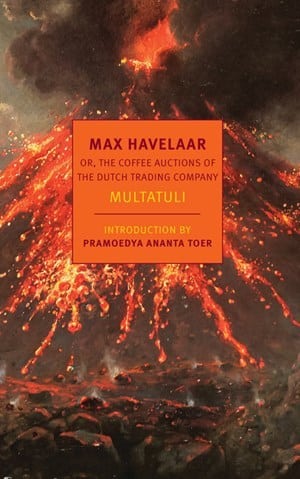

The ‘sublime work’ he refers to is Max Havelaar. Speaking before him, Arnon Grunberg described the literary power of Multatuli’s other works, like Love Letters and Ideas, in which the concept of ‘truth’ is crucial. He sketched Multatuli as a writer conversant with all things human. On a talk show, he warned against the dangers of describing Multatuli as a saint, because ‘saints usually aren’t very good writers’.

Nevertheless, a few days later historian Tineke Bennema complained in de Volkskrant that Multatuli is unduly ‘praised to the high heavens’ as a sort of ‘romantic rebel’, whereas she had learned in secondary school that he was hardly anticolonial or revolutionary. She wants to see Max Havelaar ‘valued for all its beauty in the context of its time’, but not as a political charge with lasting validity:

‘The book adds nothing to the present-day discussion about our past because it does not deal with the essence of the injustice: Dutch colonial rule. The book therefore cannot help the Dutch overcome their continued trepidation at taking responsibility for the full scope of the colonial past, including their recently proven war crimes.

Dutch war crimes

This perspective demonstrates how poorly Multatuli is read, even by historians who study the colonial past of the Netherlands. How can one say that Multatuli hesitated to point out Dutch war crimes in the Dutch East Indies? ‘One day’, he wrote in Max Havelaar’s most well-known story, ‘Saijah was roaming around in a village that had just been captured by the Dutch forces, and was therefore in flames. [He] found the corpse of Adinda’s father with a bayonet wound in his chest. Next to him, Saijah saw Adinda’s three murdered brothers, young men, hardly more than children, and a little way off lay the corpse of Adinda, naked and brutally violated.’[1]

Eduard Douwes Dekker in 1853

Eduard Douwes Dekker in 1853© Wikipedia

Here, Multatuli testifies to a gruesome war crime committed by the Dutch military. With the word ‘therefore’ he makes clear – as he explained in Idea 304 – that this was no isolated “incident” but common practice:

‘I alleged that a village was burning because it had been captured by Dutch soldiers. Herein clearly lies the accusation that our forces acted disgracefully in these disputed territories. And I – a man who tends to mean quite precisely what he says when he writes it – would like to clarify here that it was indeed my intention to place blame on those highly paid and heavily armed purveyors of high Dutch civilization and other virtues.

Yes, the village was captured by Dutch soldiers and was therefore in flames. Dutch heroic virtue is followed by fire. Dutch victory leads to destruction. Dutch military action brings despair.’

Provo’s predecessor

Is the author of the ‘book that killed colonialism’ (as Pramoedya Ananta Toer described Max Havelaar in The New York Times) above critique? Of course not. Multatuli-bashing is a time-worn tradition, and one that keeps his significance alive. I have always found it amusing, without letting it get to me too much.

I first read Max Havelaar, Love Letters, and a good many of his Ideas in 1966-67; I was around fifteen. Multatuli became my political leader and moral compass. Not a saint, but a hero, an ancestor of the Provos who, just as Multatuli had a century earlier, challenged abuses of power and authority both on societal and personal levels. In his pleas for free love and condemnation of the sexist upbringing of girls, Multatuli even went beyond Provo. Idea 195 turned me, for one, into a determined feminist:

Liefdesbrieven (Love Letters), De Arbeiderspers, 2020

Liefdesbrieven (Love Letters), De Arbeiderspers, 2020‘What are you doing to our daughters, oh morality! You force them into lies and hypocrisy. They are not allowed to know what they know, to feel what they feel, to desire what they desire, to be what they are.

“Girls don’t do that. Girls don’t say that. Girls don’t ask that. Girls don’t speak that way.”

Behold, the fabric of this upbringing. And when such a poor, swaddled child believes, accepts, obeys… when she, wholly submissive, has spent her precious youth pruning and plucking, smothering and stifling her desire, her spirit, her mind… when she has twisted, crumpled, and wasted herself to remain good – morality calls that good! – then some fellow might reward her goodness by appointing her the keeper of his linen closet and turning her into the machine that warrants and maintains his honourable masculinity. It’s certainly worth the effort, ladies!’

It was not long before I discovered that as a twenty-two-year-old comptroller on Sumatra, Eduard Douwes Dekker had had the thirteen-year-old girl Si Oepi Keteh at his disposal to maintain his ‘honourable masculinity’. But as a child of my time – the liberating sixties – I took no offence. Many gatekeepers of decency did that sort of thing; gentlemen whose behaviour had already been answered for by my other literary heroes, Ter Braak and Du Perron. Venturing out with a much older man, certainly one as brilliant as Multatuli, seemed pretty thrilling to me.

And I was not the only one who saw him as a liberator. On the occasion of Multatuli’s 100th birthday in 1920, historian Jeannette van den Bergh van Eysinga wrote: ‘In large part, Dutch women owe their liberation from the shackles of morality and tradition to the ferocious criticisms of the man who wrote Ideas.’

In The Minotaur of our Morals: Multatuli as a Herald of Feminism (2010), the researchers Myriam Everard and Ulla Jansz mapped, for the first time, the significance of Multatuli’s work for the first as well as the second waves of feminism. ‘We are talking about a radical kind of feminism – a feminism that not only addresses the subordination of women by men in both family and society, but also presents a sharp critique of Christian sexual morality.’

#MeToo

Feminists have never directly criticized Multatuli’s sexual escapades or his preference for young girls, but perhaps the time is now ripe. I have recently been asking myself how, without speaking in puritanical anachronisms, we might understand Multatuli’s pleas for sexual liberation in the light of #MeToo. Was his motto from Love Letters – that ‘pleasure is virtue’ – truly written to champion the right to sexual self-determination for women and girls? Or was he, like many #MeToo perpetrators, mostly just trying to legitimize his own promiscuity? And if the latter is the case, then does that take away from the significance of his work for feminist movements?

The Trouw columnist Ger Groot first alerted me to the possible comparisons between Multatuli and the sexual offenders who have been indicted thanks to the #MeToo movement. Having read one of my articles, he discerned a parallel between the behaviours of the 19th-century character Miss Laps from Woutertje Pieterse, and the television star Bill Cosby.

I had written that Miss Laps is much more interesting than most people think. Besides her role as the “reformed bigot” (as I was taught to read her as a schoolgirl and throughout my higher education in Dutch studies), Multatuli also portrays her as a lecherous bachelorette who intoxicates the seventeen-year-old Wouter to coax him into her bed. Multatuli praises the intrepid way the approximately thirty-year-old Kristien Laps attempts to satisfy her sexual hunger, but stipulates that Wouter does not allow himself to be fondled against his will. Although he flees from her arms because he sees his girlfriend Femke in the street, he is rather taken by the advances of the woman who was once his downstairs neighbour.

Even though Multatuli emphasizes Wouter’s pleasure in the dalliance, Groot compares Miss Laps to the Italian film director Asia Argento – a driving force behind #MeToo – who at the age of 37 had sex with an actor twenty years younger against his will. Hammering the point home, Groot goes on to accuse feminists of tolerating “rotten apples” in their own circles:

‘It seems that abuses committed by women are more readily condoned than those committed by men. As demonstrated around ten years ago by the writer Elsbeth Etty, it is but a small step further to forgiveness, and even adulation. Asked about her literary hero, she cited Miss Laps from Multatuli’s Woutertje Pieterse. At one point, this bigot assaults little Wouter, having intoxicated him like a Bill Cosby avant-la-lettre. Laps, for Etty, is therefore “in all her humanity, one of the most interesting female characters in 19th-century literature”.’

Eduard Douwes Dekker's first wife, Everdine (Tine) Huberta van Wijnbergen,

Eduard Douwes Dekker's first wife, Everdine (Tine) Huberta van Wijnbergen,© Wikipedia

This critique gave me pause for closer reflection, particularly because Groot’s anachronistic comparison is entirely in line with the earlier moralizing reproaches of Multatuli (and his admirers). As its arguments place prudishness on a pedestal, #MeToo now faces similar critiques.

‘#MeToo raised a real problem, but also brought with it the message that sex is wrong and dangerous’, writes the columnist Daniela Hoogiemstra. To reverse this backlash, she asks that we ‘protect the idea that women are just as physical as men,’ a perspective that Multatuli sought to promote more than a century ago. In 1846 he wrote to his bride-to-be Everdine van Wijnbergen of his certainty that, when it comes to physicality, ‘your sex is just the same as ours, and when it comes to less modest women, perhaps even more so.’ According to Multatuli, sexual abuse – both in and outside of marriage – was a function of the abominable and hypocritical morals against which he fought in both word and deed. And however promiscuous and adulterous Multatuli may have been, he passionately defended the equality of all people, regardless of their sex, class, or skin colour. His pleas for sexual liberation continue to inspire. But unlike when I was fifteen, it is no longer possible for me to accept his relationship with thirteen-year-old Si Oepi Keteh without critique. This relationship was, by definition, unequal.

Si Oepi

In Max Havelaar, Si Oepi (little lady) Keteh is mentioned by her true name, but without any indication that this little daughter of Datoe Keteh, the leader of Aceh, was gifted to Havelaar by her father in exchange for a positive report on his pepper plantation. This information stems from Multatuli’s widow Mimi Hamminck Schepel. She described this girl as his ‘first wife’ in response to a note added by Multatuli in the 1875 edition of Havelaar, in which he explains: ‘the naive Si Oepi Keteh was one of my first loves.’ According to Mimi, ‘the young comptroller asked for her, and her father considered it an honour to give her to him, the civil head of the town.’: ‘She lived with him for as long as he remained in Natal, and later went with him to Padang. […] Si Oepi Keteh was his first wife. He named her Clio.’

E. du Perron cites a section of this passage in The Man from Lebak, and suggests that Mimi called Si Oepi Multatuli’s ‘first wife’ in the ‘typical vocabulary of the time’, possibly to indicate that she was actually Multatuli’s first sex partner, not his first wedded wife.

Eduard Douwes Dekker's second wife, Maria (Mimi) Frederika Cornelia Hamminck Schepel

Eduard Douwes Dekker's second wife, Maria (Mimi) Frederika Cornelia Hamminck Schepel© Wikipedia

According to Olf Praamstra in a recent article, however, it is likely that she was in fact his first wife. He emphasizes the interpretation put forth by the Indonesian author Situ Situmorang, who assessed Multatuli’s wedding parties in Natal, and concluded that Douwes Dekker was officially married to the thirteen-year-old. According to Situmorang, those parties would have been seen as adat selamatans, honouring Si Oepi Keteh’s family in the tradition of local wedding customs. ‘She was, therefore,’ says Praamstra, ‘not his girlfriend, concubine, or njai, as claimed by Multatuli’s biographers, but on the grounds of the adat – his legally wedded wife.’ He notes that Multatuli’s biographers paid little heed to his relationship to Si Oepi Keteh:

‘Not that they ignore it completely, but they write about it in a way that attempts to smooth the whole thing over. Si Oepi Keteh is either his concubine, njai, or girlfriend, which suggests that the possession of a njai in those times was generally acceptable. The fact that she was very young, they write, must also be seen in the context of the time. According to Dik van der Meulen and Paul van ‘t Veer, a thirteen-year-old woman on Sumatra had reached marrying age; according to Van ‘t Veer she may even have been on the older side. He isn’t bothered by the fact that she is used as a bartering tool either. That, too, was common practice, or as Hans van Straten calls it: “a standard form of quiet corruption in the colonies back then”.’

These are the well-known, intolerable modes of reasoning with which unacceptable historical practices, like slavery, are relativized and explained away. At the same time, passing judgement on injustices committed in the past without any historical context hardly delivers a clearer picture. When it comes to Multatuli’s relationship with Si Oepi, biographers mainly suffer from a lack of information. All they have is one scene in Max Havelaar, in which Multatuli mocks the arrogant attitude of his self-aggrandizing alter ego, who spends many hours unhappily stuck on a boat with ‘that dumb Datoe and his kid’.

The only other sources that researchers have to go on are the statements by Mimi, regarding the 1875 footnote, and a single letter by Multatuli in which he mentions the name Clio. As much as it might be commonly accepted, and indeed is plausible that he used her as a sex slave, there is no real proof of that. There has never been any research done into Si Oepi, a gap in our knowledge that urgently needs filling.

My property

Multatuli may have kept his relationship with Si Oepi Keteh under wraps, but he did extensively record his further history as a ladies’ man. ‘Why am I not allowed to touch you, embrace you, press you against my heart as my own property! There is no way around it, I love you, and behold, I love you sensually!’ he wrote as a forty-three-year-old married man to his admirer Mimi Haminck Schepel, twenty years his junior. The letter in which Multatuli blatantly insists upon sex with her can be found in the collection of Love Letters in the Privédomein series published by De Arbeiderspers, which has been reissued on the occasion of Multatuli’s 200th birthday, and for which I wrote an introduction.

Like everything that Multatuli wrote, this correspondence, too, is a work of literature. The sensual love letters are particularly topical in the #MeToo era. As I re-read them, I asked myself, for example, how I would react to sexual advances from someone who saw me as his ‘property’.

New English edition of Max Havelaar, 2019

New English edition of Max Havelaar, 2019After spending a night on the author’s chaise longue in the Multatuli museum, the literary historian Marleen de Vries wondered if, had she been twenty years old in 1862, she would have been one of Multatuli’s admirers, and allowed herself to be seduced by him. ‘For sure’, she thinks. I, too, have asked myself those questions, but my answers are less certain. That’s not because Multatuli comes across in his letters – in the words of De Vries – as a ‘dirty old man’, nor because of his exhibitionist elaborations about his ‘amourettes’, but because of his urge to possess.

Ultimately, there is no evidence that Multatuli coerced his ‘groupies’ into sexual contact. He urged them to liberate themselves from the straightjacket of a morality grounded in religious conventions that robs women and girls of their right to sexual self-determination. His motto ‘pleasure is a virtue’ remains a source of inspiration, in spite of the hypocritical moralizers who accuse Multatuli of serving his own promiscuous desires. Even if that had been the case, as far as I am concerned this does not take away from the significance of his revolutionary body of work, nor from his unsurpassed literary quality.